Everyone knows the ECB will be announcing their own QE plan to save Europe. I guess they’ve seen how fantastic QE has done in reviving the Japanese and U.S. economies. One problem. The ECB doesn’t have the ability to execute their QE plan without the central banks of the various European countries doing the actual buying of debt. As John Hussman points out, the announcement will be met with great fanfare and the usual reaction of a stock market surge (because that is the only real purpose of QE). But Germany is the only party that matters. Their debt currently carries a negative yield out through 5 years. Buying that debt will guarantee massive future losses. Therefore, they will not buy it. The European QE is the last dying gasp. When Greece exits the EU, humungous losses will be experienced by banks across the world. The end is in sight.

Last week, the Swiss National Bank abandoned its attempt to tie the Swiss franc to the euro. For the past three years, the SNB has been trying to keep the franc from appreciating relative to the rest of Europe by accumulating euros and issuing francs. As the size of Switzerland’s foreign exchange holdings began to spiral out of control, Switzerland finally pulled the plug. The Swiss franc immediately soared by 49% (from 0.83 euros/franc to 1.24 euros/franc), but later stabilized to about 1 euro/franc. While numerous motives have been attributed to the Swiss National Bank, the SNB made its reasons clear: “The euro has depreciated considerably against the US dollar and this, in turn, has caused the Swiss franc to weaken against the US dollar. In these circumstances, the SNB concluded that enforcing and maintaining the minimum exchange rate for the Swiss franc against the euro is no longer justified.” In effect, the SNB simply did what the German Bundesbank wishes it could do: abandon the policies of European Central Bank president Mario Draghi, and the euro printing inclinations he embraces.

A quick update on what we call our “joint parity” estimates of currency valuation (see our recent discussion of the Japanese Yen in Iceberg at the Starboard Bow). Considering long-term purchasing power parity (which certainly does not hold in the short-run) jointly with interest rate parity (see Valuing Foreign Currencies), we presently estimate reasonable valuations of about $1.35 for the euro, and about $1.13 for the Swiss Franc – so after the wild currency moves of last week, we suddenly view the Swissie to be almost precisely where we think it should be relative to the dollar. At least one hedge fund and a number of FX brokerages were wiped out last week as their customers were caught with leveraged short positions against the franc. Data from the CME shows asset managers and leveraged money heavily short the euro (with commercial dealers on the other side), and by our estimates, the decline in the euro is overextended. That’s a high-risk combination for euro shorts.

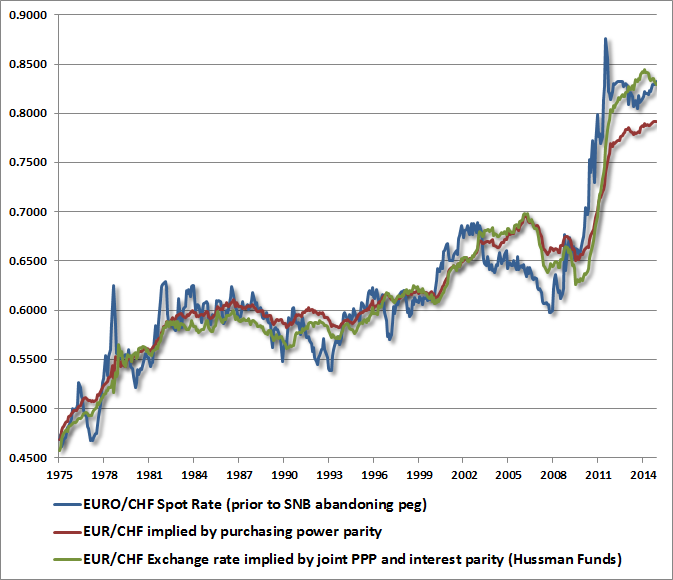

The chart below may offer some insight into what the SNB was thinking last week, from the perspective of our own joint-parity estimates of currency valuation. The chart reflects data just before the SNB abandoned its peg to the euro (data for the euro reflects the German DM prior to 1999, appropriately scaled). Back in August 2011, the Swiss franc surged to significant overvaluation relative to the euro. That’s when the SNB instituted the peg, attempting to hold the exchange rate at 1.20 francs per euro (just under 0.84 euros per franc). Prior to last week’s move, the overvaluation of the franc – relative to the euro – was no longer evident, and the franc had become substantially undervalued relative to the dollar. Having abandoned that peg, the franc has surged to what we view as fair value relative to the U.S. dollar.

Notably, the FX markets are providing some information here. From the standpoint of the EUR/CHF, the current exchange rate (now about 1.0 euros per franc) suddenly opens up a fresh gap versus the euro, which would be eliminated at a USD/EUR exchange rate of about $1.35/euro. That is, a fair value of 1.13 USD/CHF divided by a fair value of 0.84 EUR/CHF implies a fair value of 1.35 USD/EUR. Put simply, we view the Swiss franc as fairly valued against the U.S. dollar, but the U.S. dollar as overvalued relative to the euro (and most currencies). Conversely, from the standpoint of the dollar, the euro appears to have overshot to the downside. We expect that the Swiss franc will move back toward about 0.84 euros/franc (about 1.20 francs/euro), but not by depreciating sharply relative to the dollar. Rather we expect that both the dollar and the Swiss franc are likely to depreciate relative to the euro – conversely, that the euro is likely to appreciate relative to the dollar and the franc.

This week, the European Central Bank will authorize a fresh program of quantitative easing in Europe. My impression is that the structure of this venture will be far different from what seems to be commonly envisioned (and priced into an exchange rate that is has already overshot to the downside). The political realities for Germany have led it to shift its focus from opposing QE outright to changing the structure under which QE will proceed. It’s that potential impact on the structure of QE that seems underappreciated. Germany has two primary interests here. One is to ensure that any losses are borne by the individual member states, and the second is that as few euros as possible are created with the backing of questionable sovereign debt. Put simply, Germany’s agreement to allow QE to proceed is likely attached to particular strings that limit its exposure to the sovereign debt of its less credit-worthy neighbors.

Under Article 16 of the Protocol that established the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), the ECB Governing Council has the exclusive right to authorize the creation of euros, but either the ECB or the individual national central banks can issue those euros. The ECB will authorize a large QE program this week, but my impression is that the details will leave the ECB itself responsible for executing only a fraction of the announced program, with the remaining majority of the program (perhaps 60-75%) being nothing more than the option for each national central bank to purchase its own country’s government bonds, at its own discretion, and its own risk. Moreover, that option is likely to be limited to something on the order of 25% of the outstanding government debt of each respective country.

With German government debt trading at negative yields out to maturities of 5 years, German buying of German debt would essentially guarantee a loss to the Bundesbank. As a result, the likelihood that Germany will act on the option to buy that debt seems rather slim. The same argument holds, if to a lesser extent, for other credit-worthy countries in the Eurozone, which means that the bulk of that option will be taken up by smaller and less credit-worthy members. With a cap of perhaps 25% of total government debt, the actual size of QE when implemented is likely to be dramatically smaller than whatever number is announced this week. That certainly doesn’t rule out an ebullient knee-jerk response to whatever massive number is announced, but pay attention to the details, because they are likely to have a significant effect on what happens next. We’ll see.

Bottom line – “authorize” is a slippery word.

Financial services needs to do just that. Service an economy. It isn’t an economy by itself. Interest can only be paid as a result of that borrowed capital being used for profitable business purposes (or by printing counterfeit money, wtf). Those ships have long since sailed. This ponzi ain’t gonna end well.