I love reading quotes from Hussman in 2000 and 2007. The air is getting pretty thin up here. A stock market driven by Google, Apple, Netflix and a few other tech darlings with no earnings does not make a market. Time is running out for the bulls. The same morons on CNBC ridiculed and scorned his facts then and they scorn and ridicule him now. Do I trust Jim Cramer and Steve Liesman or John Hussman? Guess. Here is the most pertinent portion of Hussman’s weekly analysis:

“The Nifty Fifty appeared to rise up from the ocean; it was as though all of the U.S. but Nebraska had sunk into the sea. The two-tier market really consisted of one tier and a lot of rubble down below. What held the Nifty Fifty up? The same thing that held up tulip-bulb prices long ago in Holland – popular delusions and the madness of crowds. The delusion was that these companies were so good that it didn’t matter what you paid for them; their inexorable growth would bail you out.”

Forbes Magazine during the 50% market collapse of 1973-74

Last week was a rather exasperating exercise in two-tiered markets; a type of divergence between the broad market and a handful of glamourous “concept” stocks that has often marked the wildest and most joyous points of reckless abandon in the market cycle, at least for speculators not tethered by traditional measures of value or historical experience. I’ll spare the list of names, which should be obvious to investors by their confetti.

Near the end of speculative runs, the market’s most glamourous concept stocks often carry significant market capitalizations, and therefore drive movements in the capitalization-weighted indices without broad participation from the rank-and-file. In the short-term, that can be uncomfortable for hedged-equity strategies that are long a broad portfolio of value-oriented stocks and hedged with an offsetting short position in the major indices. Even if the cap-weighted indices outperform the portfolio of individual stocks by a few percent, that difference shows up as a loss of a few percent in the overall hedged position. It’s easier to be patient when one recognizes that these episodes are temporary, and typically represent a significant red flag for the equity market.

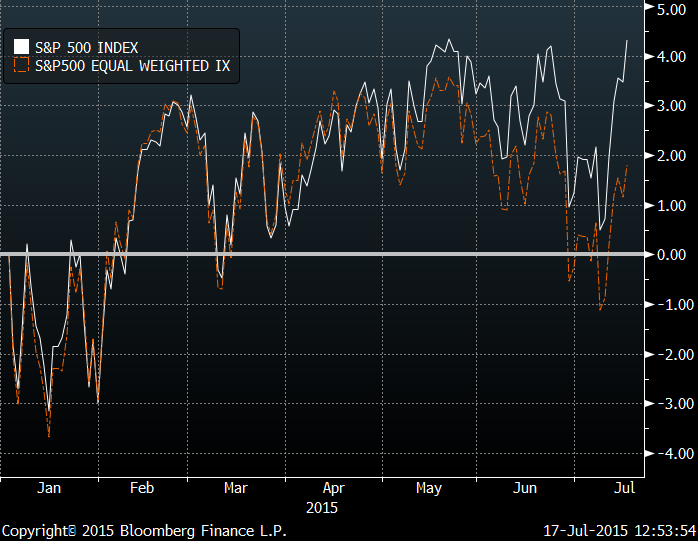

A progressive internal deterioration of the market has been increasingly evident in recent months, and became severe last week. For example, the chart below compares the S&P 500 Index to the same 500 component stocks, but weighted equally rather than by market capitalization. While the difference may not seem significant, it also implies that even an equally-weighted portfolio of S&P 500 stocks, hedged with the S&P 500 index itself, would have lost several percent since mid-April.

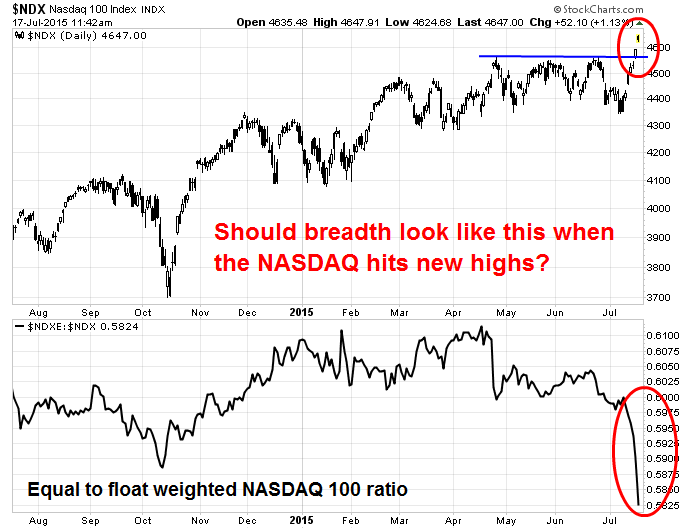

The same observation holds for the Nasdaq index. The chart below is from analyst Cam Hui, showing the Nasdaq 100 Index along with the ratio of the equal-weighted index to the float-weighted index. What’s going on is that a handful of very, very large cap stocks account for an increasing share of the net gain, while the rank-and-file have been largely stagnant or in retreat.

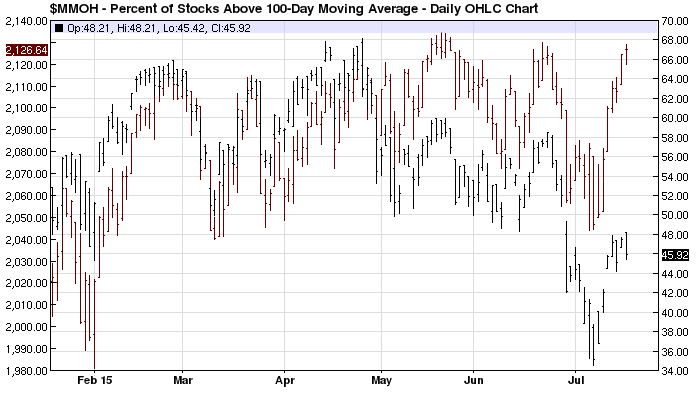

Other measures of market participation have been equally problematic. The chart below compares the S&P 500 Index (upper red bars, left scale) with the percentage of stocks trading above their 100-day moving average (lower black bars, right scale). Fewer than half of all U.S. stocks remain above their 100-day moving averages, and only about half are above their 200-day averages.

As I’ve emphasized nearly every week since mid-2014 (when we completed the awkward transition from our pre-2009 methods to our present methods of classifying market return/risk profiles – see A Better Lesson Than “This Time is Different” and Voting Machine, Weighing Machine for the full narrative), the central lesson of market cycles across history, and even the most recent full cycle since 2007, is that the behavior of market internals is central to distinguishing an overvalued market that collapses from an overvalued market that continues to advance. Importantly, market outcomes in response to Federal Reserve easing are also dependent on the behavior of market internals. When market internals have deteriorated following extreme overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions, even Federal Reserve easing has not reliably supported the stock market.

We’re certainly open to the possibility that the market could recruit more favorable uniformity, and thereby signal a more robust willingness of investors to speculate. That wouldn’t make valuations any less obscene, but it would defer our immediate concerns about severe market losses. Still, the central feature to watch in that regard is market behavior across a wide range of individual securities, industries, sectors, and security types – not simply central bank behavior.

As a reminder of how all this works, it may be helpful to recall how this same situation (which we’ve previously described in real-time with the same concerns) has played out historically. Recall that our measures of market internals shifted negative in October 2000, following what was until that point a reserved but still constructive stance. Once that period of persistent overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions was joined by a breakdown in market internals, all bets were off, even bets that might rely on the Federal Reserve.

See, as the 2000-2002 bear market was just starting, the Federal Reserve under Alan Greenspan immediately shifted to fresh monetary easing, cutting the Federal funds rate and the Discount rate on January 3, 2001. That move did encourage a short-term market bounce, but the subsequent lesson investors should have learned (and the same one I reviewed in detail last week in relation to the 2007-2009 collapse) is also the lesson that investors are likely to experience over the completion of the present cycle: Once extreme overvalued, overbought, overbullish conditions are joined by a deterioration in market internals, even easier Fed policy does not provide reliable support for the stock market. As I wrote on January 8, 2001:

“Investors haven’t learned their lesson. Despite the brutalization of New Economy stocks over the past year, ignorance and greed obey no master. Following the Fed move, investors went straight for the glamour tech stocks, dumping utilities, pharmaceuticals, consumer staples, hospital stocks, insurance stocks – anything that smacked of safety or value. Investors are behaving like an ex-con, whose first impulse after getting out of the joint is to knock over the nearest liquor store… the immediate response of investors to interest rate cuts was to create a two-tiered market. And unfortunately, it’s exactly that failing ‘trend uniformity’ that places this advance in danger. Historically, sound market rallies are marked by uniform action across a wide range of sectors.”

“To illustrate the probable epilogue to the current bubble, we’ve calculated price targets for some of the glamour techs, based on current revenues per share, multiplied by the median price/revenue ratio over the bull market period 1991-1999.

Cisco Systems: $18 ¾, 52-week high: $82

Sun Microsystems: $4 ½, 52-week high: $64

EMC: $10, 52-week high: $105

Oracle: $6 7/8, 52-week high: $46

Get used to those itty-bitty prices. That’s what happens when companies keep splitting their stock during a bubble.”

Alan Abelson kindly featured those comments in Barron’s Magazine, followed that Monday morning by a round of dismissive remarks by several CNBC anchors. No matter – those projections turned out to be optimistic. As it happened, the 2002 lows for these “four horsemen of the internet” took Cisco to $8.60, Sun to $2.42, EMC to $3.83, and Oracle to $7.32. We forget that the most popular large-cap speculative leaders at the 2000 peak lost 92% of their value over the completion of the cycle. It feels better to forget.

Despite extreme losses in the glamour stocks that comprised the prevailing “concept” in prior episodes of speculative overvaluation, the character of those stocks has often varied. In the advance leading to the 1929 peak, the darlings included AT&T, Bethlehem Steel, General Electric, Montgomery Ward, National Cash Register, and Radio Corporation of America – companies that embraced the expanding world of department stores, communication, and industry. Those stocks would lose an average of 93% of their value by 1932.

In the late-1960’s, the glamour stocks were instead focused on rapid growth; “-onics” and “tronics” stocks, as well as conglomerates that grew mainly through acquisitions. In 1972, the focus turned back to blue chips – the “one decision” Nifty Fifty stocks that investors believed could be held forever because of their promising growth. Many of these stocks did indeed turn out to enjoy tremendous earnings and revenue growth over the following decades, but that didn’t prevent deep losses in the interim. The names included household names like Du Pont, Eastman Kodak, Exxon, Ford Motor, General Electric, General Motors, Goodyear, IBM, McDonalds, Mobil, Motorola, PepsiCo, Philip Morris, Polaroid, Sears, Sony, and Westinghouse. The fact that these were major companies didn’t prevent this list from losing over 65% of its value in the 1973-74 collapse (even though corporate earnings grew by nearly 70% over the same period):

Today, the focus is squarely on companies that have enjoyed striking “network effects” – where users are drawn to a given company largely because other uses are already there. While these network effects have generated enormous revenues, today’s glamour stocks also trade at earnings and price/revenue multiples that have historically been reserved for companies at a much earlier point in their growth trajectories, not for mature companies with already overwhelming market share.

As was the case during the tech bubble and the housing bubble, disagreement is what makes markets, and we respect that others have different views. From a historical standpoint, however, when the equity market has joined persistent overvalued, overbought, overbullish extremes with deteriorating market internals, with a cherry on top featuring two-tiered speculation in glamour stocks and heavy new issuance of stock by companies that predominantly have no earnings, we find it difficult to find any precedent that hasn’t worked out quite badly. We’re open to an improvement in market internals that might defer our concerns, but the financial markets simply have never enjoyed hypervalued speculative advances without those speculative gains being completely transitory over the completion of the market cycle.

In short, recent market action has featured a two-tiered market in large-capitalization glamour stocks that we’ve seen before at speculative extremes throughout history. This is uncomfortable for hedged-equity in the short-run, because the glamour stocks drive gains in the major indices that aren’t sufficiently matched by gains in broadly constructed stock portfolios – particularly those following value-conscious strategies. It’s helpful to recognize that action for what it is, and for what – historically – has typically followed. None of that means that the discomfort won’t continue for a while longer, but history teaches that it’s an awful idea to try to “play” the mature phase of a speculative trend, especially once market internals have already given way.

I thought it was a post about this:

It would probably be appropriate to more clearly explain to your readers that you are quoting Hussman verbatim for THE ENTIRE ARTICLE except for the opening paragraph…

My readers know that I post Hussman’s stuff every Monday. They also know that I put my own words in bold. Thanks for your concern asshole.

@Sustainable Gains … you’re lucky Admin hasn’t yet implemented his IQ test yet before letting people post. I’m thinking you might not have qualified.

You ain’t the only one though. I mean … on the “beer” thread, there are actually people (long time posters) who actually WANT TO BUY that helium beer!!

Roll Over Beethoven

by Jesse

If you have not done so already, it is probably time to take profits in US equities.

The advance is so narrow it is almost chilling, with the upward momentum in stocks down to a handful of new era tech giants.

Down volume was almost double up volume on the broader market. The wiseguys were taking profits.

The Paypal ‘ipo’ was brought out today in the fluffy new era atmosphere, and did well. And this was probably the greatest motivator behind this latest ‘rally.’

IBM beat EPS estimates but missed revenues after the bull. IBM is, alas, a once great company that is now a dead man walking, sustained by accounting theatrics at these price levels.

These jokers are financial TV are incredible. I watched CNBC this afternoon and I could almost feel my IQ declining. They could, and probably should, be selling blenders on the Home Shopping Network.

Dear Administrator –

Thanks for explaining “My readers know that I post Hussman’s stuff every Monday. They also know that I put my own words in bold.”

But I must respectfully disagree. If you truly respect Hussman’s analysis, you should give him full credit for his own work, every time. It’s not hard, and you do it for all your other commentary either “submitted by” or as a “guest post”. By doing otherwise, you just make yourself look bad.

Besides, although regulars who read your site religiously _might_ know your approach, your stuff gets read more widely. Your article was cross-posted elsewhere, by people who apparently don’t know your style. So really you have no basis for making the assumption that someone would know that you cross-posted Hussman’s work without proper attribution.