Guest Post by Hardscrabble Farmer

Most of what I write turns into some sort of parable. I discuss my chickens and by the time the story is over it becomes apparent that I wasn’t really talking about chickens, but something else instead. It was never my intent, but it has become a signature of sorts, a means for communicating in times when open discussion has become fraught with risk. As I talk with others in the open world I have discovered that I am not alone, that this literary quirk is instead a form of self-defense against The Silencing, a means to talk about what really concerns us but which may not be spoken in polite society if we wish to remain true to our conscience.

Slate Magazine, of all places, discovers that there is only one way to deal with certain problems and that is to understand the cause and formulate a proper response. No wild-eyed theories that defy reality, no learning to embrace the new experience regardless of the outcomes, just a sober realization of facts and a determination to correct the problem.

An eye opener, it’s.

Oh, No, Not Knotweed!

It’s been nearly four years since I bought hypodermic needles at a CVS, squatted in my backyard, and drew them full of glyphosate. I’d done my best to build a little garden in Brooklyn, only to see the ground begin to vanish beneath the fastest-growing plant I had ever seen. It sprouted in April with a pair of tiny, beet-red leaves between the flagstones, and poked up like asparagus through the mulch. By May the leaves were flat and green and bigger than my hands, and the stems as round as a silver dollar. My neighbor’s yard provided a preview of what was coming my way: a grove as thick as a cornfield, 10 feet high, from the windows to the lot line. I had to kill the knotweed.

I tried a few different approaches: Yanking it out stalk by stalk was a sweaty, summer-long game of whack-a-mole—a thankless full-time job. Then a friend and I spent one long night digging a 10-by-4-foot trench, lining it with black contractor bags, and refilling it with dirt. It looked like we were trying to bury something, and in a way we were: the knotweed rhizomes—the plant’s creeping rootstalks—under our feet, searching for a ray of light.

I was facing twin threats. The knotweed would kill my plants within months and prevent anything else from growing. But spraying the yard with Round-Up, Monsanto’s powerful herbicide, would kill everything in days. Which is why I bought the needles. The idea, which was tested in the journal Conservation Evidence, was to inject the plant’s hollow, jointed canes with weedkiller, shooting herbicide into its roots but sparing innocent neighbors from the deadly spray.

In the moment, this felt absurd, a demented instruction from the Wile E. Coyote guide to gardening. This was before I knew that two full-time knotweed fighters had, in 2004, shot glyphosate into more than 28,000 knotweed stems along Oregon’s Sandy River. Or that in the United Kingdom, it has been a crime to plant or transport unsealed knotweed since 1990. Or that right here in New York City, more than 200 acres of parkland have been overtaken by the plant.

Anyway, it didn’t work.

Japanese knotweed has come a long way since Philipp Franz von Siebold, the doctor-in-residence for the Dutch at Nagasaki, brought it to the Utrecht plant fair in the Netherlands in the 1840s. The gold-medal shrub was prized for its “gracious flowers” and advertised as ornament, medicine, wind shelter, soil retainer, dune stabilizer, cattle feed, and insect pollinator. The stems could be dried to make matchsticks, or cut and cooked like rhubarb. It crested in the dog days of summer with tassels of tiny white buds. Oh, and it grew with “great vigor.”

In 1850, von Siebold shipped a bundle of knotweed plants to Kew Gardens. From there, carried by gardeners, contractors, and floods, knotweed conquered the British Isles and dug its roots deep into the English psyche. In 2008, the novelist Jeffrey Archer released a best-selling revenge novel in which the protagonist crafts a strategy to sabotage an enemy via knotweed propagation. Archer believed knotweed had undermined the foundation of his own family home. The plant has worked its way into British vernacular—last year, a group of parliamentarians called Theresa May the “Japanese knotweed prime minister”; in April, soccer legend Gary Neville berated losing Manchester United players as knotweed in the locker room, “attacking the foundations of the house”—and has sprouted an industry of knotweed removal specialists, lawyers who chase their vans, and a tabloid press that can’t get enough of the invasive shrub and the human conflict it creates.

England and Wales are the most dramatic examples of knotweed’s spread in the West, but knotweed endures across the channel, too—as the most expensive invasive plant crisis on the continent, according to a 2009 study. And in recent decades, Japanese knotweed has colonized the Northeastern United States, the spine of the Appalachians, the Great Lakes states, and the Pacific Northwest. Infestation is “rapid and devastating,” one researcher wrote. “The plants are characterized by a strong will to live,” wrote another. In New Hampshire, a knotweed researcher told me he had found knotweed systems—almost certainly just one plant, connected underground—as large as 32,000 square feet, more than half the size of a football field.

Along streams and rivers, knotweed grows into a wall that hides the water. Along roads, its arching canes can make it hard to see around bends. In Bronx River Forest, knotweed once grew so thick that driving along its paths was “like being in a knotweed carwash,” New York City conservation manager Michael Mendez told me. “There were people living in the knotweed,” he recalled. It was a good place to hide.

Knotweed can grow through cracks in cement, between floorboards, and out from the joints in a stone wall. “You can see it everywhere, along the roadside, in every city,” said Jatinder Aulakh, an assistant weed scientist at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. In the landscapes it has infested, it is impossible to imagine what was there before—and harder still to foresee a future without it. “There is no insect, pest, or disease in the United States,” Aulakh said, “that can keep it in check.”

In the summer of 2013, a lab technician in the suburbs of Birmingham, England, beat his wife to death with a perfume bottle before killing himself several days later. In the interim, Kenneth McRae outlined the way he understood his own unraveling in a suicide note. “I believe I was not an evil man until the balance of my mind was disturbed by the fact that there is a patch of Japanese knotweed which has been growing over our boundary fence on the Rowley Regis Golf Course,” he wrote. “It has proved impossible to stop, and has made our unmortgaged property unsaleable. … The worry of it migrating onto our garden and subsequently undermining the structure over the next few years, with consequent legal battles which we won’t win, has led to my growing madness.”

No plant can excuse such violence. But the fear McRae describes, says Mark Montaldo, is not exactly irrational. Montaldo is a lawyer in Liverpool and the head of civil litigation at the firm Cobleys Solicitors. His three most profitable lines of work are personal injury suits, bad landlords, and Japanese knotweed.

When I first spoke to Montaldo, he was riding his bicycle outside the city. It was a pleasant day in early April, and across Great Britain, chalk-white knotweed stems were awakening underground. Montaldo expects the summer will bring his firm hundreds of inquiries from buyers fighting sellers, homeowners fighting contractors, and neighbors fighting neighbors—all over Fallopia japonica. “People are thinking, ‘It could totally make my house worthless,’ ” Montaldo told me. “And it can.”

At the heart of the Great British Knotweed Panic is the fear that knotweed will make your house fall down. The U.K. has made knotweed disclosure mandatory on all deeds of sale. British banks will not issue a mortgage to a property with knotweed on its grounds, or to one with knotweed growing nearby, unless a management plan is in place. In February, HSBC clarified its mortgage policy in a letter to a parliamentary committee, which was committed to addressing knotweed even in the midst of the Brexit chaos. Any knotweed growing within seven meters of a property is “unacceptable security,” said the country’s largest bank. A management plan can be a long and costly ordeal, with a bedroom-size clump of knotweed requiring thousands of dollars of treatment over several years. Homeowners with negligent neighbors or few resources have little recourse at all. In 2016, not far from the Rowley Regis course, a retired butcher named William Jones hanged himself in his home. At an inquest, his wife said he had been troubled by, among other things, the financial implications of knotweed on a piece of land he’d bought. “Bill was a very strong character,” she later told the Telegraph. “But this was something he couldn’t cope with.”

There is some dispute among biologists and engineers over whether the plant poses quite the threat banks and courts say it does. But there is no doubt that knotweed in the U.K. is perceived as an affliction, a shameful outbreak. “It’s a little bit like an STD,” said Mike Clough, a knotweed treatment specialist whose clients sometimes request that he arrive in an unmarked van. “You don’t want to talk about it, you don’t want people to know you’ve had it, you just want to get rid of it.” (Clough told me he routinely sees the plant intrude on inside spaces. “We did one hotel, where on opening day the hotel had lumps in the carpet,” he said. “They rolled it back, and knotweed was coming through.”)

How did knotweed become so widespread in the U.K.? Only a female specimen had made the trip from Nagasaki to Utrecht to London to the watersheds of Ireland and Wales, so there were no knotweed seeds in the British Isles, just fragments of the plant’s underground stems. But that was enough. In 2000, biologists Michelle Hollingsworth and John Bailey analyzed 150 samples from across the U.K. and concluded that British knotweed was all a clone of that original plant, now one of the world’s largest. The DNA was identical. Not just one species but a single plant had conquered the entire United Kingdom.

That was possible because of knotweed’s astounding powers of asexual reproduction: A new plant can grow from a fingernail-size piece of root, and a century of building homes, roads, ditches, and levees—and dumping the dirt wherever it was convenient—helped put those fragments everywhere. So did flooding, which carried bits of root downstream. Barriers like walls and roads were no obstacle because knotweed roots can stretch as far as 70 feet from the nearest stem.

Did I mention that it’s really hard to kill?

Dan Jones—Twitter handle Knotweed_Doktor—has a Ph.D. in biology and runs a consultancy firm in Cardiff, Wales, called Advanced Invasives. When we spoke in March, he was preparing to fly to Southern California, whose famous dry climate means it is not a great place for knotweed—which means it is a great place for Jones to take his family on vacation. “I quite like that, and so does my wife, because I’m not spotting it.”

Advanced Invasives is in the business of tamping down knotweed using techniques like digging, cutting, and spraying a cocktail of herbicides. But Jones is forthright about the challenges involved and about the fact that living with knotweed might be your only option. His thesis, published last year in the journal Biological Invasions (less exciting than it sounds), was the most extensive field-based study of treating large knotweed patches. Its conclusion: “No treatment completely eradicated F. Japonica.”

Consider a new housing development in Wales, where Jones was brought in to assess an infestation that measured about 50 by 60 feet. If Jones had his men dig down enough into the earth to be sure of catching the deepest chunks of root, he was looking at excavating nearly 5,000 cubic yards of soil—almost an entire American football field, dug out three feet deep—which would then have to be placed in a specially designated landfill, since knotweed had been classified by the government as “controlled waste,” the same category as some byproducts of nuclear power plants. The cost for off-site disposal would run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Removing knotweed from the site of the London Olympics was estimated to have cost about 70 million pounds.

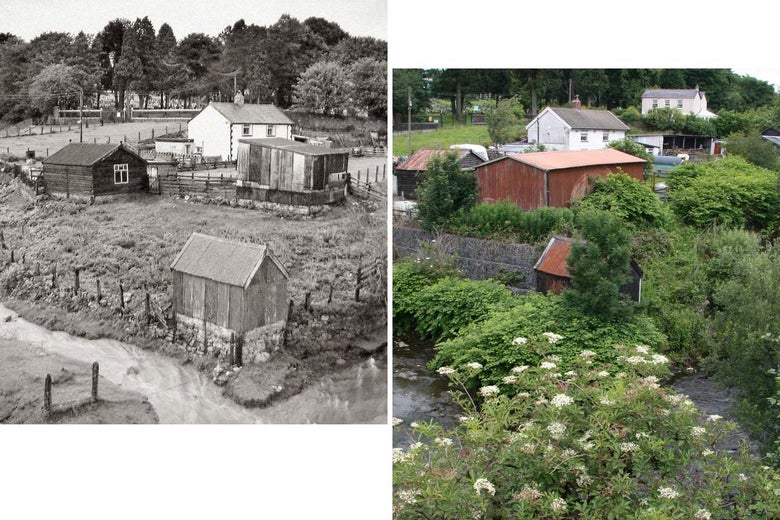

Knotweed removal is even more complicated near streams and rivers, where the plant has found its deepest foothold, and overlapping property claims make large-scale cooperation difficult. Digging is often infeasible because running water is ever-present and likely to sprinkle rhizome fragments down the watercourse. Spraying is fraught because herbicide use is regulated around freshwater streams. Jones showed me side-by-side photos of a farmstead at the headwaters of the River Rhymney in South Wales, one taken in 1984 and the second in 2012. The first shows the confluence of two streams at the crook of the property. The second shows a forest of knotweed.

In the late 1860s, James Hogg was running a nursery on East 84th Street in Manhattan when he received a gift from his brother Thomas, who was working in Japan. James was an acquaintance of the couple that started the New York Botanical Garden, and sometime around the turn of the 20th century, his friends decided to try a new planting in the Bronx.

You know what happened next. Knotweed has flourished in the U.S.—especially in the past few decades, driven by construction and flooding. Experts also believe that climate change plays a role, with disruptions like heavier rainfall, warmer winters, and the desynchronization of native plants and animals all favoring hardy invaders like knotweed. Knotweed is “out of control,” says the New York City Parks Department, which has spent almost $1 million treating just 30 acres of knotweed citywide since 2010.

The first American knotweed lawsuit, as far as I can tell, was decided in 2014, when Cynthia and Alan Inman of Scarsdale, New York, sued the owners of the shopping center next door, alleging the defendants had allowed knotweed to thrive on their property and, from there, undermine the Inmans’ property value. They won $535,000 in damages.

But because knotweed still has a relatively low profile in the United States, landowners can be confused and surprised when they first confront the plant. Carly Reynolds bought an old farmhouse on 13 acres in Rome, New York, in 2016, hoping to turn it into a restaurant and event space. The next spring, she found knotweed growing through the floorboards—offshoots from a thicket along the property boundary. “I was turning into a crazed person, watching it take over the property,” she recalled. Now she and her friends dedicate several days a year to knotweed control just to keep the plant at bay.

Knotweed is one in a long list of invasive plants to have prompted concern in the U.S. Pigweed, which plagues soybean farmers in the Midwest, has developed herbicide-resistant strains that alarm farmers and fascinate scientists. Californians are reckoning with their iconic eucalyptus trees, which are delightfully fragrant, non-native, and highly flammable. The panic over kudzu in the American South, while appealing to writers searching for symbolism in the landscape, turned out to have been quite a bit overblown.

“Frankly, kudzu pales by comparison in its effects to Japanese knotweed,” Robert Naczi, a curator of North American botany at the New York Botanical Garden, told me. “There are plenty of invasives [where] yes, they spread, but they’ve occupied most of the habitat that they will occupy. Japanese knotweed still has a ways to go and it appears it will—unless we do something we’ve not yet discovered—be successful in dominating the state of New York.”

The biggest problem with knotweed, Naczi explained, is that it grows so thickly there is no room for anything else. “I don’t want to ascribe moral agency to the plant,” he says. “It’s not an evil plant. It’s doing what a plant does. But Japanese knotweed is a very serious invasive. A very, very problematic species. One of the worst invasive species in Northeastern North America.”

We are only beginning to understand knotweed’s ecological impacts. Chad Hammer, a graduate student and researcher at the University of New Hampshire who has been traveling New England in search of knotweed, is one of the first people to study the plant’s environmental effects. Last year, he found that 30,000-square-foot infestation in Coos County, New Hampshire. In Vermont, he saw how the devastating floods unleashed by Hurricane Irene had, among other things, sprinkled the state’s watersheds with knotweed rhizomes. But it doesn’t take a hurricane: “When you’re working in a stream after a high-flow event, you’re very frequently seeing Japanese knotweed stems floating past you,” he told me. “They land somewhere else, and they start a new colony over there.”

Hammer has found three changes in infested landscapes. First, knotweed grows so densely that virtually no sunlight hits the ground in a knotweed forest. In the massive Coos County patch, he said, there were no more than two other plant species growing in the knotweed’s shadow. That, in turn, reduces the number of bugs that might live in that landscape. Where there are fewer bugs there are fewer birds, and so on.

Second, and relatedly, new trees can’t grow in a knotweed monoculture, which is very bad for streams. In a native New England forest, dead branches play an indispensable role in shaping streams. Woody debris feeds bugs who feed trout. Logs create eddies and pools, which enhance stream habitats and provide places for sediment to collect, improving water quality downstream. Fewer trees, fewer pools, fewer bugs, fewer trout.

In knotweed colonies, Hammer also found that the ground was barren of organic material, which increased the likelihood of soil erosion during rainstorms. Sure enough, when Hammer looked at the boulders and cobbles in streambeds near knotweed growth, he found that rocks downstream from the plant were more likely to be coated in silt. That’s bad for fish and invertebrates who use the clean rocks for nesting, he said, and bad for humans whose water, down the line, may be carrying chemicals from fertilized soil that makes its way into the stream.

Hammer’s findings are a reminder that knotweed’s impact goes far beyond rickety floorboards and cracked asphalt. And yet, one thing nobody has learned about the plant is how to economically and effectively eliminate it. “It gives me tremendous frustration to give you the truth,” Naczi told me. “Our understanding is far behind the plant’s ability to expand and invade.”

Not everyone is as apocalyptic as Naczi. Several ecologists I spoke to argue that lawyers and contractors in the U.K. have sown paranoia over a pesky shrub. “The contractors’ marketing is highly spurious, but you have to give them credit,” says Max Wade, an engineer with the firm AECOM who has argued that knotweed is no more likely to undermine a house than a tree. (Still, you can kill a tree in a day, and you won’t have to tell the guy who buys your house that you did.) “They’ve done a great job convincing us it’s a demon plant.” Even Jones, the Knotweed_Doktor himself, decries what he calls “hysterical” media coverage, as well as a weed-control industry he thinks has taken advantage of a desperate and ill-informed clientele.

“It’s good for business if everyone’s terrified by it,” says the British biologist John Bailey, who is known to his peers as the God of Knotweed. “But nobody talks about the benefits.” Such as: Knotweed’s late-blooming flowers provide a snack for bees in the waning days of summer and produce a mild-flavored honey. Researchers in the Czech Republic have concluded that knotweed can be effectively processed into briquette biofuels because it grows so fast. Knotweed is rich in resveratrol, the family of molecules present in red wine and thought to be responsible for the health benefits associated with wine consumption. If it’s not growing in contaminated urban soil, it’s edible, with a lemony flavor and juicy crunch. Also, it’s just really interesting.

“It’s a giant natural experiment that allows us to think about how plants are evolving,” says Christina Richards, a biologist from the University of South Florida. Richards is fascinated by how knotweed exhibits diversity without genetic variation. It’s the antithesis of Darwin’s finches, which mated and mutated to suit their new habitats. Some knotweed hybridizes and evolves, but much of it does not change. It’s as at home on the volcanic slopes of Mt. Fuji as it is in New York parking lots and English gardens. It is a globalized super-specimen. “It loves so many types of environments—it’s a dream if you wanted to think about exposing a single individual to billions of different conditions.”

“So what makes it a dream for you is exactly what makes it a nightmare for everyone else?” I asked.

“Yes,” she answered.

One thing that knotweed-loving biologists and knotweed-hating ecologists agree on is that humans have no chance of controlling the plant on a national scale. One of the most successful efforts at wild knotweed control was undertaken on Oregon’s Sandy River from 2001 to 2008, a project that super-scaled some of the techniques I had tried in the battle for my backyard—a battle that is, by the way, ongoing. Digging, cutting, injecting, spraying. Negotiating. Doing it all again, year after year.

It was an ambitious endeavor, run by the Nature Conservancy, with two full-time employees and a squad of volunteers. The team got cooperation from nearly 300 landowners to work on their properties, and some sites had to be accessed by boat. By 2008, stem count was down by 90 percent in the patches that had been treated. And yet: The team was unable to eradicate a single one of the biggest infestations, even after as many as nine treatments.

All the methods devised by man to stop knotweed are too expensive, time-consuming, and inefficient. We need a natural ally.

Enter Aphalaris itadori, a sap-sucking psyllid from Japan that eats knotweed for breakfast. (Itadori is the Japanese word for knotweed—this is the knotweed aphid.) In 2013, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Technical Advisory Group for Biological Control Agents of Weeds recommended the insect be evaluated for release in the United States.

This idea—fighting invasive species by introducing their native predators—is called biocontrol, and Roy Van Driesche, an entomologist at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst, believes it is the only approach for fighting knotweed at scale. He has been ready to drop psyllids on knotweed infestations around New England since 2011. Van Driesche has his sites. He has the money. He has watched the itadori bugs munch happily away at potted knotweed, and bred dozens of generations of these tiny critters in captivity, for more than five years. He has been waiting, fruitlessly, all that time, for the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the USDA to grant him a permit. “They can wait you to death,” he said glumly.

The thing is, itadori might not even work, and Van Driesche knows it. Trials in the U.K. have brought mixed results, in part because native anthocorids gulped down the aphid eggs. At best, Van Driesche hopes for some decline in knotweed density a decade after introduction: The idea is not to eliminate the plant, but merely to “moderate its abundance” enough that native species can begin to compete.

On a cool day in early May, I caught a train north from Grand Central to the East Bronx. I saw knotweed all along the way: out the window at a construction site, on the embankments above the highway, and among the tulips in front yards on Burke Avenue. I was heading to meet Adam Thornbrough of the New York City Parks Department for a walk in the Bronx River Forest. Today, Thornbrough says, after nearly two decades of management, this is a place where the Parks Department has beaten back one of its biggest foes.

Once, knotweed so thrived here that in high summer the asphalt paths became tunnels, dark at noon beneath canes of knotweed bending toward the light. Volunteers spaced 10 feet apart used to march through the forest swinging machetes in each hand. Paths through the bush led to homeless encampments, to what one volunteer called the “knotweed people.”

But now, Thornbrough is feeling optimistic. On the river’s east bank, years of cutting, picking, and spraying have in places reduced the plant to a few wayward, scraggly stalks. (One great thing about a paucity of native plants? It’s easier to spray herbicide.) When I visited, the park was busy with volunteers organized by the Bronx River Alliance. They didn’t need machetes anymore. Groups of high schoolers filled the bed of a pickup truck with contractor bags of knotweed. The conservation crew leader told me she is here five days a week, and knotweed takes up 85 percent of her time, but she can finally see the river.

These clearings in the Bronx River Forest are a testament to the enormous human effort required to tame the plant. Here in one of the most densely populated neighborhoods of America’s biggest, richest city, we have broken knotweed’s hold.

But turn the corner on the river’s west bank, and neither the story nor the forest floor is so sunny. There, on the other side of the river, was more knotweed than I had ever seen in my life. “The Bronx River is one of the worst bodies in the state for knotweed. It’s on all the tributaries, it’s everywhere,” said Thornbrough, as we peered into a field of stalks just over a bridge from the culled fields.

Without the fibrous roots of native plants to anchor them, the riverbanks are sloughing into the stream. “It’s a biological wasteland,” Thornbrough said. We walked for a half-mile. Trees stood overhead; weeds grew underfoot. But in between, the only living thing was knotweed.

It is my sincere desire to provide readers of this site with the best unbiased information available, and a forum where it can be discussed openly, as our Founders intended. But it is not easy nor inexpensive to do so, especially when those who wish to prevent us from making the truth known, attack us without mercy on all fronts on a daily basis. So each time you visit the site, I would ask that you consider the value that you receive and have received from The Burning Platform and the community of which you are a vital part. I can't do it all alone, and I need your help and support to keep it alive. Please consider contributing an amount commensurate to the value that you receive from this site and community, or even by becoming a sustaining supporter through periodic contributions. [Burning Platform LLC - PO Box 1520 Kulpsville, PA 19443] or Paypal

-----------------------------------------------------

To donate via Stripe, click here.

-----------------------------------------------------

Use promo code ILMF2, and save up to 66% on all MyPillow purchases. (The Burning Platform benefits when you use this promo code.)

Aesop was a Greek slave, whose fables arose from the understanding that ‘open discussion can be fraught with risk’.

And Socrates’s death reminds us still.

They would both place a wreath on your head.

A parable about progressives…….,or family?!

My interpretation – after reading a very long (don’t mind, just sayin’) article:

Communist/”progressive” thought processes appear to come from out of nowhere, but have truly slowly built from a small seed over a long time period. Minimizing the influence of communist/”progressive” thought processes seems, at first, near impossible and can cause feelings of hopelessness and delusions of impending catastrophe. Put in enough work at eradication/control, though, and just keep hammering away and eventually you can begin to see real progress. Those communist/”progressive” thought processes are never stomped out for good and it requires an ever vigilant effort to hold them in check at minimal levels because just a small amount of that venomous and destructive envy can invade and corrupt a huge, and formerly, pleasant landscape.

Am I in the ballpark or does the parable (and metaphors) symbolize something else?

Every bit as sound as my take.

Actually I was struck by just how open they were about the costs, damage and nuisance of dealing with an invasive species, undermining everything they have worked hard for and consider valuable. Just like their affinity for Game of Thrones, these hipster progs are demonstrating the true feelings that must keep very well hidden when it comes human beings. It’s just a baby step to full blown identity politics from there.

The “affinity for Game of Thrones”…yes.

Call me soft or old fashioned, but the themes and plot lines, although (sometimes) along the lines of a Shakespeare tragedy from the few I have seen, are overrun by the absolutely graphic portrayal of gore and violence. Great stories and storytelling, in my humble opinion, are great stories because they don’t need that level of graphic violence (written or acted) when including the darker aspects of humanity. I do believe that seeing things of that nature again and again over time, and that are indistinguishable from reality to our brains, will desensitize all but the saintliest of individuals and promote some depraved form of addicition.

cough… “Excuse me, President Euphemism, why do you insist on maligning innocent, traumatized, asylum-seeking Knotweeds?”

I thought it was about the invasion of Muslims.

Commie-weed.

good article ,farmer–

since we’re talking commies & progressives,here’s something that won’t surprise you guys too much but they are making things more obvious–

the red pope has called 4 global govt to supersede national govts because of the “danger” of climate change & the stance of some sovereign govts regarding immigration–

from the new american–

https://www.thenewamerican.com/culture/item/32245-pope-francis-calls-for-end-of-sovereignty-and-establishment-of-global-government?vsmaid=4572&vcid=8726

Personally I thought it was a very plantist article. I never knew Slate to engage in such plantism before. The author’s Knotweedaphobia is completely despicable. Who are they to judge?

I choose to see the bright side. It makes great honey for my bees in the fall.

Progressives/Communists will also provide great opportunities in the “fall” to snatch up assets for pennies on the dollar when the proles discover their free stuff isn’t free and start unloading houses, cars, and anything else they can no longer afford.

I get the symbolism and all, but damn that was a long article about a weed.

It wasn’t really about a weed.

I thought it was Musslemen but Progs work too.

Never fear Farmer. I heard that Al Gore has a scheme to sell knot weed credits that will eradicate the pest.

The article was very illustrative of marxo-commie-fasco-sh*t-tardism and all, and it has absolutely infiltrated from mandatory public education (we all know the ten planks, right?) and taken over BUT that reality (in this instance) disturbs me less than does the above quote. So my question is . . . HOW does speaking the truth (in a diplomatic rather than confrontational manner, of course) in ANY way violate anyone’s conscience?

Years ago, a friend of mine relayed to me that she had been trying to talk – without addressing the issue directly – to another mutual friend about a matter that is of no importance now, BUT, she said, “I was just thinking, ‘Oh for God’s sake, take a hint already.'” To which I replied, “If his behavior bothers YOU, the onus is not on him to take a hint; you might as well ask him to read your mind. The burden is yours to speak your mind, so that there is no misunderstanding.”

So, I am not true to my conscience when I fail to speak plainly. But maybe I misunderstand what you mean?

Yeah, dammit!

Sometimes you need to stop beating around the knotweed, just come out and say it. Parables dull a knife that’s directed at a target and they’re good learning tools for those observing mistakes but sometimes a fool needs to feel a sharp, cutting blade. It makes a great impression on other fools who are slow to get the point.

“HOW does speaking the truth (in a diplomatic rather than confrontational manner, of course) in ANY way violate anyone’s conscience? ”

It doesn’t. I phrased that awkwardly, my error. If you listen to your conscience and you speak the truth as you understand it, then “polite society” (and that was of course a dig against the speech police and our politically correct climate) will do it’s very best to marginalize and silence you. It happened to me and it cost me a great deal. It took ten years for me to start writing again and then only in the most circumspect way. These efforts to drive open and honest discourse into The Silence, where the individual is so frightened and humiliated by the apparatus of The State and MSM that they censor their own thoughts.

And that’s what they want, just like 1984. You become your own prison guard for your thoughts.

The problem of course is that human beings are subject to Newton’s Third Law and what cannot be said manifests itself in a different way. That’s what this article was in my estimation. Knotweed is knotwhat this story was really about and even the author isn’t aware of it.

I wonder if females, knowingly or not, are behind this. I remember bitching about a friend who was staying with me with her two kids, basically taking advantage of my kindness. I never said anything to my friend about it but I would bitch to my mother about it. My brother was listening to me and said, “Women never come out and say what’s on their mind. Men say exactly what’s on their mind and get it over with. Women never do that and simply bitch about it.” And he was exactly right! So are the females the ones that are behind all of this, which is pushing us to self-censorship?

This is the only prison where the warden greets you with a key to your cell and a tube of lube.

it’s ok to be knotweed

If only Dung had considered your moniker 1st.

It comes with a thumb all up in it.

sigh

enema people

Knotweed is like Kudzu in the south. Both are edible. If people started harvesting it, they could seriously reduce it. Knotweed is also used in herbal medicine.

If you unleash pigs on Kudzu, they will destroy the plants because they dig up the roots and eat them. I wonder if that could work with Knotweed.

Edit: Yes, I know it’s not really the topic, but just saying.

We used pigs to eradicate a patch of it here and then woodchipped the surface heavily. there’s a beautiful stretch of meadow there now, not a trace of knotweed. So yes, it can be managed.

Thanks for the reply, Hardscrabble. At least I know that theory is workable..

You can make a bucket of ‘at strength’ Roundup and apply it to the leaves with a sponge. It should kill the rhizomes along with the plant. At the very least, you can make your property knotweed free.

I don’t use Roundup because plants can become resistant to it. They don’t seem to become resistant to natural products. The best weed killer I’ve ever used was made with 1 gallon of white vinegar, 1 cup of salt and some dish washing liquid (I use Dawn). Put the salt into the vinegar, heat it until the salt is dissolved. When it cools, add dish washing liquid. Put it in a sprayer and spray onto the surface of plants you want to get rid of. The dish washing liquid will help the mixture adhere to the plant surface. The vinegar and salt mixture is absorbed by the plant and drawn into the root, which kills it. It hasn’t failed me yet.

The most effective means of suppressing any kind of unwanted plant is to make the soil inhospitable to it’s growth. Loading the soil with carbon in the form of wood chips, keeping the Ph at 7.0, planting root intensive plantings that crowd it out- all of these are biologically safe, they improve conditions for what you want to thrive and make it difficult or impossible for the targeted species to thrive.

https://www.backtoedenfilm.com/

Thanks for the Back to Eden film reference. I’ll watch it as soon as I get a chance.

I was thinking more along the lines of: Invite the third world, become the third world. Once the invasive species drop their “anchor babies” there is no getting rid of them, and they will take over the native plants, crowding them out once and for all (us).

I actually think I may have some on the property where I live now. The plants spring up the day after I mow them. Was going to try to first kill them with a propane flame thrower (which is just pure fun in and of itself), and then drench with some vinegar/salt/soap solution.

I just drove over a blue ridge mountain pass in Virginia and the Kudzu is crazy. Hope that knotweed shit does not take over the northeast, especially since it undermines river/stream banks. Maybe the environMENTAL douchebags will concentrate on that aspect instead of the climate change bullshit, but that ain’t gonna happen. Or maybe the coming solar minimum ice age will knock it down. (But if it is up in Coos county NH that is unlikely).

The genie is out of the bottle. Kudzu then Knotweed then ???. Monkey Wards then Kmart then Walmart. Myspace then Facebook. The world evolves, then we adapt. Same as it ever was. Looking forward to your schtick HSF (Is Vodka coming haha?). Will be in touch later to see what I can help you with.