On May 19, 1536, Anne Boleyn, the infamous second wife of King Henry VIII, is executed on charges including adultery, incest and conspiracy against the king.

Catherine of Aragon

King Henry had become enamored of Anne Boleyn in the mid-1520s, when she returned from serving in the French court and became a lady-in-waiting to his first wife, Catherine of Aragon.

Dark-haired, with an olive complexion and a long, elegant neck, Anne was not said to be a great beauty, but she clearly captivated the king. As Catherine had failed to produce a male heir, Henry transferred his hopes for the future continuation of his royal line to Anne, and set about getting a divorce or annulment so he could marry her.

For six years, while his advisers worked on what became known as “the King’s great matter,” Henry and Anne courted first discreetly, then openly—angering Catherine and her powerful allies, including her nephew, Emperor Charles V.

In 1532, the savvy and ruthless Thomas Cromwell won control of the king’s council and engineered a daring revolution—a break with the Catholic Church, and Henry’s installation as supreme head of the Church of England. Many unhappy Britons blamed Anne, whose sympathies lay with England’s Protestant reformers even before the Church’s steadfast opposition turned her against it.

Jane Seymour

At Queen Anne’s coronation in June 1533, she was nearly six months pregnant, and in September she gave birth to a girl, Elizabeth, rather than the much-longed-for male heir. She later had two stillborn children, and suffered a miscarriage in January 1536; the fetus appeared to be male.

By that time, Anne’s relationship with Henry had soured, and he had his eye on her lady-in-waiting, the demure Jane Seymour.

After Anne’s latest miscarriage, and the death of Catherine that same month, rumors began flying that Henry wanted to get rid of Anne so he could marry Jane. (Had he attempted to annul his second marriage while Catherine was still alive, it would have raised speculation that his first marriage was valid after all.)

Henry had apparently convinced himself that Anne had seduced him by witchcraft, and also told Cromwell (Anne’s former ally, now her rival for power in Henry’s court) that he wanted to take steps towards repairing relations with Emperor Charles.

Arrest and Imprisonment

Seeing Anne’s weak position, her many enemies jumped at the chance to bring about the downfall of “the Concubine,” and launched an investigation that compiled evidence against her.

After Mark Smeaton, a court musician, confessed (possibly under torture) that he had committed adultery with the queen, the drama was set in motion at the May Day celebration at the king’s riverside palace at Greenwich.

King Henry left suddenly in the middle of the day’s jousting tournament, which featured Anne’s brother George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford, and Sir Henry Norris, one of the king’s closest friends and a royal officer in his household. He gave no explanation for his departure to Queen Anne, whom he would never see again.

In quick succession, Norris and Rochford were both arrested on charges of adultery with the queen (incest, in Rochford’s case) and plotting with her against her husband. Sir Frances Weston and Sir William Brereton were arrested in the following days on similar charges, while Queen Anne herself was taken into custody at Greenwich on May 2.

Duke of Norfolk

Led before the investigators (chief among them her own uncle, the Duke of Norfolk) to hear the charges of “evil behavior” against her, she was subsequently imprisoned in the Tower of London.

The trial of Smeaton, Weston, Brereton and Norris took place in Westminster Hall on May 12. At the conclusion of the trial, the court sentenced all four men to be hanged, drawn and quartered. Three days later, Anne and her brother, Lord Rochford, went on trial in the Great Hall of the Tower of London.

The Duke of Norfolk presided over the trial as lord high steward, representing the king. The most damning evidence against Rochford was the testimony of his own jealous wife, who claimed “undue familiarity” between him and his sister.

Trial of Anne Boleyn

As for Anne, most historians agree she was almost certainly not guilty of the charges against her. She never admitted to any wrongdoing, the evidence against her was weak and it seems highly unlikely she would have endangered her position by adultery or conspiring to harm the king, whose favor she depended upon so greatly.

Still, Anne and Rochford were found guilty as charged, and Norfolk pronounced the sentence: Both were to be burnt or executed according to the king’s wishes.

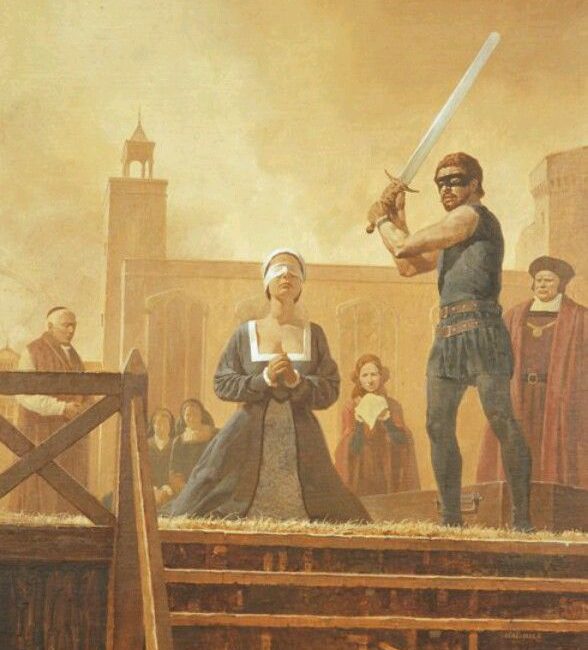

On May 17, the five condemned men were executed on Tower Hill, but Henry showed mercy to his queen, calling in the “hangman of Calais” so that she could be beheaded with the sword rather than the axe.

Anne Boleyn Execution

On the morning of May 19, a small crowd gathered on Tower Green as Anne Boleyn—clad in a dark grey gown and ermine mantle, her hair covered by a headdress over a white linen coif—approached her final fate.

After begging to be allowed to address the crowd, Anne spoke simply: “Masters, I here humbly submit me to the law as the law hath judged me, and as for mine offences, I here accuse no man. God knoweth them; I remit them to God, beseeching Him to have mercy on my soul.” Finally, she asked Jesus Christ to “save my sovereign and master the King, the most godly, noble and gentle Prince that is, and long to reign over you.”

With a swift blow from the executioner’s sword, Anne Boleyn was dead. Less than 24 hours later, Henry was formally betrothed to Jane Seymour; they married some 10 days after the execution.

While Queen Jane did give birth to the long-awaited son, who would succeed Henry as King Edward VI at the tender age of nine, it would be his daughter with Anne Boleyn who would go on to rule England for more than 40 years as the most celebrated Tudor monarch: Queen Elizabeth I.

It is my sincere desire to provide readers of this site with the best unbiased information available, and a forum where it can be discussed openly, as our Founders intended. But it is not easy nor inexpensive to do so, especially when those who wish to prevent us from making the truth known, attack us without mercy on all fronts on a daily basis. So each time you visit the site, I would ask that you consider the value that you receive and have received from The Burning Platform and the community of which you are a vital part. I can't do it all alone, and I need your help and support to keep it alive. Please consider contributing an amount commensurate to the value that you receive from this site and community, or even by becoming a sustaining supporter through periodic contributions. [Burning Platform LLC - PO Box 1520 Kulpsville, PA 19443] or Paypal

-----------------------------------------------------

To donate via Stripe, click here.

-----------------------------------------------------

Use promo code ILMF2, and save up to 66% on all MyPillow purchases. (The Burning Platform benefits when you use this promo code.)

“cameras add #10”? Paintings = #300-#400.

The beginning of the end of a unified Christian church , now replaced by Judaized heresy which is tolerance for debauchery couched in churchianity, debt slavery for all and mass murder on an ever increasing scale.

Philip II: (1527-1598)

William Thomas Walsh

http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=1889B28539B7506D637C3D5605BFD2A0

Could anything worse than all these miseries fall upon afflicted

Christendom? Those who asked the question in that year 1527

thought not. Charles’ aunt, Catherine of England, who had known so

many sorrows since that day when she embarked at Coruña before

the turn of the century, seems to have had some insight into the end

of so much military glory. On May tenth, before she knew of the sack

of Rome, she wrote her Imperial nephew from “Grannuche” a

pathetic but arresting letter in Spanish.

“Most High and Powerful Lord,—I hardly know how to confess

the many obligations in which I stand towards Your Highness for the

many favors conferred upon me. I hold it to be that Your Highness

has chosen to show sorrow for my death, perceiving that neither my

existence nor my services are such as to deserve being recalled to

your memory. And yet, trusting in Your Highness’ innate kindness

and virtue, I will, with the help of God, employ my life in the

furtherance of those objects which may be for your Highness’

service, though my abilities be scanty, and my powers small . . .

“As I fear that my letter may be odious to Your Highness, as

written by one inexperienced in these matters, I shall say no more

here than beg and entreat your Highness to have pity on so much

bloodshed and perdition of souls so costly and redeemed at such

price, bearing in mind that this world is perishable and of short

duration, and the next one eternal. There is urgent need that peace

between Christian princes be concluded, before God sends down

His scourge, which cannot tarry if these quarrels and disagreements

continue between Christian princes. If in the expression of these

sentiments I have given the least offense, I beg your Highness to

pardon me; my ignorance alone is the cause. God have you in His

keeping.

“Your good aunt Katherina.”15

A characteristic letter of the youngest daughter of Ferdinand and

Isabel, with nothing in it of any trouble personal to her. Yet within a

month Charles was to receive from his ambassador in England the

startling news that Henry, inflamed with lust for Anne Boleyn, and

artfully managed by upstarts and sons of usurers, was planning—but

secretly, for fear of a popular uprising in her favor—to divorce her. It

was now Charles who caught a terrifying glimpse of the abyss that

was only beginning to open before the feet of all Christian men.

“You may well imagine how sorry We were,” he wrote Mendoza,

“to hear of a case so scandalous in itself, and entailing such

lamentable consequences for the future, from which evils

innumerable must inevitably arise, especially at the present juncture.

We cannot desert this Queen, Our good Aunt, in her trouble.”

Nevertheless he thought that “moderation and kind remonstrances”

might be best for the present, and he inclosed a letter in his own

handwriting, written in cipher, “with infinite trouble to Ourselves,” to

be delivered to King Henry.

He was anxious just then to draw Henry from his alliance with

Francis, which the sack of Rome had cemented. “Knowing his great

personal virtues, his elevation of mind, his good and righteous

intentions, and the perfect love he has always borne towards Us and

Our affairs, We cannot in any manner be persuaded to believe in so

strange a determination as this on the part of His Serenity, a step

which would so astonish the whole world, were it to be carried into

execution . . . The good qualities of the Queen . . . the honesty and

peace in which they have lived for so many years . . . To which we

may add that having, as they have, so sweet a princess for their

daughter, it is not to be presumed that His Serenity would consent to

have her or her mother dishonored, a thing so monstrous of itself

and wholly without precedent in ancient or modern history . . . Nor is

it likely that these proceedings originate with His Serenity, but with

persons who bear ill-will towards His Most Serene Highness, the

Queen, and Ourselves, and care not what evils and disasters may

spring therefrom. . . .”16

How true this was, all Christendom was only too soon to learn.

An age was in dissolution, an epoch had come to an end, a strange

new phase was being ushered in by wars, plagues, tempests, and all

manner of strange phenomena. Diseases unknown or forgotten by

history made their appearance.17 The “dancing sickness,” whose

victims sometimes continued to dance for weeks, attacked whole

communities. There had been several epidemics in England of a

fatal new disease called the English sweating sickness; it seldom

troubled foreigners, while Englishmen abroad died of it. In northern

Europe, especially in the new Protestant communities, there was an

increase of psychic disorders, hallucinations and suicides, mass

hysteria. The year after the sack of Rome the French army before

Naples was destroyed by spotted fever. For six whole years there

was famine, with great summer moisture and heat, and warm

winters; in 1528 an extensive drought, and swarms of locusts and

fiery meteors in northern Germany; in 1529 a bloody rain was

reported at Cremona; the torrent of Saint Vitus, four days of rain and

flood, in Germany; plague in Vienna and among the Turks who

besieged it; a terrifying comet in August

Henry the Eighth’s Divorce [1533]

T WAS in the tragic year 1533, when Philip was six years old, and

his mother lay at the point of death, that the famous divorce case

reached its unholy climax. No one could have foreseen, when Henry

VIII first met Anne Boleyn in 1522, that the fate of the world for

centuries was at stake. Kings paying lip service to Christianity had

broken marriage vows for a thousand years or more, and a few had

died in their sins; yet never before had a king been willing to rend the

seamless garment of the Church to make a woman of her sort a

queen.

By the year 1530 Wolsey was disgraced and dead, the more

sinister Thomas Cromwell was high in the King’s favor; and with the

counsel of this subtle politician Henry was advancing rapidly toward

his object. From several universities, where it was always possible to

find elements of dissent, he had obtained favorable opinions. All over

Europe he spent money liberally, buying what would now be called

“expert” advice. There was a doctor at Siena known as Il Decio who

wrote out a dissertation for him. Charles’ ambassador, reporting the

fact on September eleventh, 1530, added, “Decio has promised also

to allegate for us, and although I am not fond of this sort of thing, I

am ready for the sake of that poor Queen to pay in this instance as

well and perhaps better than the English.”

Two months later Micer Mai wrote from Rome that “Among those

who have given their opinions here in favor of the King is a

converted Jew, who now goes by the name of Marco Gabriello, to

whom the King of England has offered as much money as he may

ask, having instructed his ambassadors to . . . have him sent to

England. As this man’s journey cannot be for a good purpose, we

are afraid that with the votes the King has got already and with

Gabriello’s presence in England, the Parliament may be persuaded

to grant that which he has so long threatened. . . . I have written

Scalenga at Asti to arrest the Jew if he pass there. . . . Antonio de

Leyva should do the same, if the Jew go through Milan.”1 But it

appears that Gabriello got to England, and delivered his expert

opinion.

Henry had Stokesley, his solicitor, consult various Jews in

Venice, Bologna and elsewhere. By this time, however, the heavy

influence of Charles V began to make itself felt even in Venice, and

officials there put an end to the researches of Francischinus; not,

however, before he had obtained, and sent off to England, an

imposing opinion in Hebrew from Rabbi Jacob Rafael b. Yehiel

Hayyim Peglione of Modena. Neither Messer Francischinus nor his

master Ghinucci at Venice, who sent it off to Henry, seems to have

been aware that the good rabbi, weighing the disputed texts in

Deuteronomy XXV and Leviticus XVIII, 16, concluded that Henry had

been married to Catherine in the eyes of God, and could not annul

the contract on the grounds alleged. This document (now in the

British Museum) was not used in the divorce proceedings.2

The fears of Micer Mai about the next English Parliament proved

to be only too well conceived. The astute little group who had wound

their influence about the mind and will of Henry VIII had seen to it

that there would be on hand enough politicians, bound by interest or

subserviency to the King’s cause, to pass any measures the

monarch might desire. “Great industry had been used in managing

elections for this Parliament, and they were so successful in

returning such members as the King wanted, that he was resolved to

continue them till they had done his work, both in the affair of the

Divorce, and the business of the Reformation. Some of the

spirituality also ran on with the stream, not knowing where it would

carry them.”3

Sir Thomas More opened the session of 1530. His name,

however, did not appear among the signatories of a letter sent to

Pope Clement on July thirtieth, signed by the Archbishops of York

and Canterbury, the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk, several earls, four

bishops, and various knights, barons and abbots. The letter, couched

in a very lofty, moral tone, accused the Pope of ingratitude to King

Henry, the justice of whose cause had been acknowledged by the

most famous universities—indeed, this was a “universally

acknowledged truth. . . . We do again and again beseech you for our

Lord Jesus Christ’s sake, whose vicar on earth you stile yourself;

and that you now conform your actions to that title, by pronouncing

your sentence to the glory and praise of God. . . .”4

Clement’s reply to this pious insolence was affectionate, tactful,

grave for the most part, but now and then mildly witty; it is a

neglected apologia, in his own words, for his conduct of the difficult

case; and it leaves no doubt he understood its importance.

5

. . . “As

for the present case, We shall give no hindrance or delay to its

decision, . . . being desirous to free your king, your queen and Our

own selves from this troublesome affair.” . . . But the Parliament

should not require more “than We can without offending God

perform.” Clement must have known of course that the secret

instigator of the parliamentary letter was Henry, or Henry’s new

master, and he must have concluded by then that what Henry

wanted was not a fair trial, but his own way.

“This answer,” wrote the historian of Parliament, “had very little

effect on the minds of those who were before resolved to abrogate

the Pope’s supremacy in England and strip the Church of its

overgrown possessions.” There lay the real issue. Secret and

powerful forces, which had not yet disclosed their hand, were using

the King’s weariness of his wife, his infatuation for Anne, and his

hope of a male heir as instruments in pursuit of their own ends.

Charles and his advisers knew this before the end of 1530, and

inclined to blame the Pope, especially for his allowing Henry to get

opinions from the universities.

Catherine wrote, in Spanish, a burning letter to the Pope, (of

which Chapuys sent the Emperor a copy on December twenty-first)

complaining that her just petitions had been neglected. “I beg and

entreat Your Holiness not to allow any further delays in this trial, but

at once pronounce final sentence in the shortest way. . . .

“Some days ago Micer Mai, the ambassador of his Imperial

Majesty and my solicitor in this case, wrote to say that Your Holiness

had promised him to renew the brief which Your Holiness issued at

Bologna, and another one commanding the King my Lord to dismiss

and cast away this woman with whom he lives. On hearing of it,

these ‘good people’ who have placed and still keep the King my Lord

in this awkward position, began to give way, considering themselves

lost. . . . One thing I should like Your Holiness to be aware of,

namely, that my plea is not against the King my Lord, but against the

inventors and abettors of this cause.

“I trust so much in the natural goodness and virtues of the King

my Lord that if I could only have him two months with me, as he

used to be, I alone should be powerful enough to make him forget

the past; but as they know this to be true, they do not let him live with

me. These are my real enemies who wage such constant war

against me; some of them that the bad counsel they gave the King

should not become public, though they have been already well paid

for it, and others that they may rob and plunder as much as they

can. . . . These are the people from whom spring the threats and

bravado proffered against Your Holiness; they are the sole inventors

of them, not the King my Lord. It is, therefore, urgent that Your

Holiness put a very strong bit in their mouths, which is no other than

the sentence.”6

Clement hesitated between conflicting counsels, hoping no

doubt that the infatuation of Henry would burn out before it set all

Christendom afire. Meanwhile “the inventors and abettors” of the

cause célèbre were justifying only too well the Queen’s fears of their

astuteness. They were a small but extremely powerful minority, more

international than English in their loyalties and associations. They

had needed only an occasion and a pretext. They found both in

Henry’s infatuation.

When haven’t the English been wicked?

Two things I have can glean from the photos;

—1) Inbreeding is a terrible thing

—2) Those Royals really need to get more sun

So … they had ‘daytime shows’ — a.k.a. Soap Operas — in the 16th century.

Who knew?

Folks sure seemed to take stuff way too seriously back then … glad we’ve got a sense of humor these days …