The United States: Are the Seeds Already Sown for the Next Macro-Market Deflation Crisis?

By John Mauldin

Greg Weldon has long been my favorite slicer and dicer of data – his charts and insights on charts really help me keep my eyes peeled. But in order to get across to us the drastic state of the economy as we plunge headlong into 2014 – a year that we all know will be pivotal – Greg has felt it necessary to resort to a rather trenchant metaphor from the year just past. Yes, says Greg, the economy is … Breaking Bad.

But – listen up now – bad is now good. At least temporarily.

Good, because bad macroeconomic data means an ongoing (if slightly tapering) supply of monetary steroids (Greg’s term) will be forthcoming from our pushers, the central banks of the developed world.

Greg reminds us that the “Breaking Bad Era” actually got underway decades ago. He traces its history back to pre-WWII manipulation of the bullion market; to the historic post-WWII Bretton Woods agreement that gave the US currency “seigniorage,” thus setting it up to become the world’s reserve currency; and right on through to the closing of the gold window by Richard Nixon in 1971.

Since then, the US economy has been dependent on steady – and of course ever-growing – doses of monetary steroids, with only one brief drug-free stint in the Paul Volcker Rehabilitation Center in the 1980s.

And of course the Greenspan Fed did try to do the tighten-up from time to time; but each attempt brought greater pain during withdrawal … and the ever-compassionate Dr. Greenspan took pity on us and increased our monetary prescription.

Now, Greg really socks it to us (and we haven’t even gotten to those charts yet … but we will):

Who, even a short ten years ago, would have ever thought that the most popular shows on US television would be about hero-serial-killers and methamphetamine ‘cooks’?? We could extrapolate to suggest that this reflects the intensifying socio-economic impact of the secular trend related to the polarization of wealth, the expanding production-output efficiency generated by technology, the rise in the level of poverty in the US, and the increased social unrest evidenced by ever more incidents of seemingly random, premeditated violence.

The story line in the award-winning US television show Breaking Bad is ‘Milton-esque’, in that it explores the internal war between good and evil as manifest within the lead character, a high school chemistry teacher who contracts brain cancer. In need of money to pay bills that his health insurance will not cover, the teacher turns to the nefarious underworld of ‘cooking’ crystal-meth.

Greed leads to violence, which in turn leads to chaos and intensifying desperation. Ultimately, things spin out of control, as the teacher-turned-meth-cook finds it impossible to maintain a balance between family values and the ruthlessness of his business.

Therein lies the analogy, as the global situation finally reached the desperation point and threatened to spiral out of control in 2008-09 … when withdrawal from Fed monetary tightening led to organ failure in the housing market, which nearly spilled over into the banking system, [leaving] the US economy perilously close to ‘death’.

We are tempted to say that the US has been in and out of a coma ever since, in the sense that “real” reflation remains flat-lined.

You get the picture.

But now Greg wants us to dig even deeper. Yes, the Fed has “saved” the banking system – for now. And yes, the Fed has refloated the US consumer – on the bloated back of the stock market. (“Note,” says Greg, “the exceptionally ‘tight’ positive-correlation between the Fed’s Balance Sheet, the US S&P 500 stock index, and US Household Net Worth” – great chart follows.)

But in doing all this saving of the economy from itself, Greg wants to argue, the Fed has already sown the seeds of the next macro-market deflationary wave. So let’s give Greg the floor and let him paint the Big Bad Picture for 2014. And be sure to catch his special offer for Outside the Box readers, at the end.

I write this note from Vancouver where I will shortly be speaking to the local CFA organization before traveling on to Edmonton and Regina to speak for their respective CFA groups. I came in to Vancouver early yesterday so that I could finally get the opportunity to meet Frank Giustra, one of the more storied and colorful names in the natural resources field. We have many mutual friends who had been suggesting we get together. The son of an immigrant miner, he is one of those wonderful rags to riches stories that you see from time to time.

Frank hosted a small dinner at his home. Randomly, there was a natural resources conference going on in Vancouver the same day, so Frank was able to get decades-long friend Frank Holmes of US Global to come along, as well as my business partner Olivier Garret, energy maven and speculator Marin Katusa, and a few others. It was one of those special nights where the conversation flowed vibrantly from one topic to the next. Of course we talked about natural resources, but also about robotics and the still-approaching Singularity, the future of work, and the nature of progress – etc. For those who aren’t familiar with Frank, he made most of his money investing in natural resources, was also a founder of the movie production giant Lionsgate, and is a running buddy of Bill Clinton’s. So naturally the talk turned to politics and movies. (Turns out Frank just purchased half the rights to Blade Runner, which may be my pick for all-time best science fiction movie. I am ready for an updated remake!)

Vancouver is one of the most beautiful cities I get to visit. The weather has been spectacular, although I’m told it will turn cold just about as soon as I head east to Edmonton and Regina.

(Wow! I just got word that my old friend Ross Beatty is in town and would like to get together. It’s been a long time. I first met him in the ’80s when he was trying to figure out how to get a little silver out of the ground. I understand that he’s made a few billion here or there in the meantime, mining all sorts of minerals and creating lots of wealth for his investors. Ross Beatty was always and still is a winner. It will be fun to catch up.)

You have a great week and stay warm.

You’re looking for his Under Armor gear analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box[email protected]

Stay Ahead of the Latest Tech News and Investing Trends…

Click here to sign up for Patrick Cox’s free daily tech news digest.

Each day, you get the three tech news stories with the biggest potential impact.

Fourteen-For-Fourteen

Fourteen Macro-Market Trading Themes to Watch For During 2014

A Preview of Our Number-One Theme: The United States

The United States: Are the Seeds Already Sown for the Next Macro-Market Deflation Crisis?

We recently finished our 2014 outlook piece entitled “Fourteen-For-Fourteen”, with fourteen separate macro-market ‘trading themes’, all of which offer numerous specific ways in which to participate in a broad and diversified batch of global markets. Our coverage extends from stock indexes, individual equities, ETFs and ETNS, foreign exchange, fixed-income, precious and industrial metals, energy, and agricultural commodities, sectors we discuss every day in our Weldon LIVE research publication.

I have teamed up with my golf buddy John Mauldin to offer a slice (no pun intended) of our first, and perhaps most important, macro-market trading-theme for 2014, as it relates to US Federal Reserve policy, the US consumer, the US stock market, and US Bonds.

(Details on how to get our “Fourteen-For-Fourteen“, at a special, discounted, Outside the Box price, can be found at the end of our preview.)

We begin with a headline that caught my eye the other morning, culled from Bloomberg …

… “India’s SENSEX rose 1.8 percent today, the most in three weeks, after an unexpected drop in factory output spurred optimism that the central bank will not raise interest rates.”

We might call this the ‘Breaking Bad Era’.

Bad is now good.

Good, because bad macro-data means … a continued flow of monetary steroids from Central Banks.

Indeed, whether it be India, the UK, Japan, the EU, or the US, bad economic data is celebrated, as is so grossly evidenced by the reaction seen on television, amid stock market exuberance and the resultant extension in net worth/wealth reflation.

Indeed, just like any addict, the global markets, not to mention the underlying global macro-economy, have come to RELY ON a steady dose of monetary steroids, without which withdrawal kicks in, muscle atrophy intensifies, and eventually organ failure ensues.

We see this already, within the US labor market … atrophy without a steady, if not ever increasing, dose of monetary “roids”.

Our regular readers know that we have been all over this ‘theme’ for years.

In my book “Gold Trading Boot Camp” (Nov-2006) I examined the then-intensifying trend towards a blow-out in the massive credit bubble in US Housing facilitated by the Fed’s response to the 1997-98 global crisis, and the 2000-01 tech-bubble-bursting crash. I laid out the scenarios in which the Federal Reserve would need to ride their monetary white-horse to the rescue, to avert a full-blown credit crash and debt deflation …

… by conducting outright purchases of US Treasury securities.

Even as late as 2006, anyone opining such a blasphemous thought was considered a monetary heretic.

Now the history books are being ‘re-written’, while the un-written mandate of the US Federal Reserve and other global Central Banks has subtly-yet-significantly shifted, exactly as we said it would way back in the nineties, from preventing a repeat of the 1970’s inflation, to circumventing a full-blown debt deflation and macro-economic depression.

We said quite blatantly, two decades ago, that … “someday the Fed will pursue inflation.”

Blasphemy !!! Pure monetary heresy !!!

Now it’s called the “new normal”.

But, as we laid-out in “Gold Trading Boot Camp”, what we now call the ‘Breaking Bad Era’ began decades ago.

We traced the history back to pre-WWII manipulation of the bullion market, the historic post-WWII Bretton Woods agreement that gave the US currency ‘seigniorage’, thus setting it up to become the ‘world’s reserve currency’, right through to the closing of the Gold window by US President Richard Nixon in August of 1971, the spark that truly started this ‘fire’.

The US macro-market has been taking monetary steroids since 1971, with a brief stint spent ‘drug free’, while residing in the Paul Volcker rehab center.

Each successive tightening brings greater pain during withdrawal, which then drives Central Bankers to increase the monetary dosage, to the point where the once unthinkable has occurred, and the Assets Held Outright by the Fed will balloon to more than $4 trillion, most of which is held in US government debt.

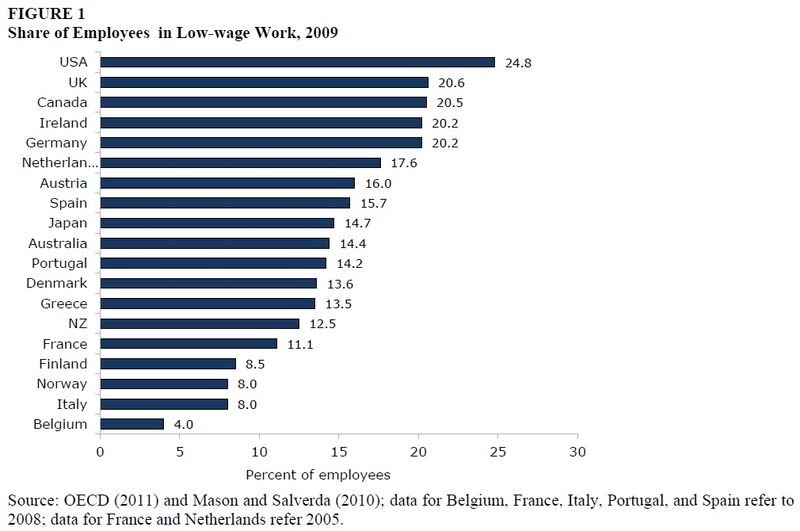

Indeed, consider this … who, even a short ten-years ago, would have ever thought that the most popular shows on US television would be about hero-serial-killers and methamphetamine ‘cooks’ ?? We could extrapolate to suggest that this reflects the intensifying socio-economic impact of the secular trend related to the polarization of wealth, the expanding production-output efficiency generated by technology, the rise in the level of poverty in the US, and the increased social unrest evidenced by evermore incidents of seemingly random, pre-meditated violence.

The story line in the award-winning US television show “Breaking Bad” is ‘Milton-esque’, in that it explores the internal war between good and evil as manifest within the lead character, a high school chemistry teacher who contracts brain cancer. In need of money to pay bills that his health insurance will not cover, the teacher turns to the nefarious underworld of ‘cooking’ crystal-meth.

Greed leads to violence, which in turn leads to chaos and intensifying desperation. Ultimately, things spin out of control, as the teacher-turned-meth-cook finds it impossible to maintain a balance between family values, and the ruthlessness of his business.

Therein lies the analogy, as the global situation finally reached the desperation point, and threatened to spiral out of control in 2008-09 … when withdrawal from Fed monetary tightening led to organ failure in the housing market, which nearly spilled over into the banking system, putting the US economy perilously close to ‘death’.

We are tempted to say that the US has been in and out of a coma ever since, in the sense that “real” reflation remains flat-lined.

Yet, there have been some bright spots, some limb movements and facial expressions emanating specifically from the US consumer, and from corporate America as it relates to streamlined efficiency and increased competitiveness.

The Fed successfully ‘saved’ the banking system, for now.

The Fed successfully kept the US consumer afloat.

Moreover, the Fed has facilitated an unprecedented reflation in US Net Worth. But, this reflation comes in PAPER wealth, NOT wage-income, which is still glaringly lacking.

Witness the chart below plotting the path of US Household Net Worth, which has spiked to a new all-time high, with a near-$22 trillion expansion from the 2009 secular crisis low.

But in so doing, we could argue that the Fed has already sown the seeds for the next macro-market deflationary wave.

We can directly connect the dots.

It all starts with Fed purchases of government debt …

… which has led to the reflation in the US equity market …

… almost single-handedly generating a huge expansion in US Net Worth.

From there we can continue to draw a straight-line to the fact that the strongest improvement within the underlying macro-economy has been seen specifically in sentiment-derived numbers …

… which leads us directly to the virtually unnoticed renewed blow-out in US consumer credit…

… which has ‘funded’ the robust recovery in retail sales and US final household demand.

And finally, it is an easy link to the upside outperformance and leadership exhibited in the stock market since the advent of QE, by the Consumer Discretionary sector.

Note the exceptionally ‘tight’ positive-correlation between the Fed’s Balance Sheet, the US S+P 500 stock index, and US Household Net Worth, as evidenced in the overlay chart below. Indeed, since the advent of QE-III the movements of the US stock market and the Fed’s Balance Sheet have become almost identical.

With US Households ‘feeling’ STRONG thanks to massive injections of monetary steroids, and a renewed feeling of invincibility among stock market investors, consumers are flexing their muscles by borrowing significant amounts of ‘cash’.

We offer hard-core data as evidence. As seen in the chart below, we can identify more months of double-digit (as in more than $10 billion) growth in the Fed’s own measure of Consumer Credit over the last three-years, than during ANY other period in the post-WWII timeline.

Note further, that the 5-Year Average of monthly borrowing has almost returned to the pre-2007 crisis highs.

In essence, we can very comfortably argue that the Fed has facilitated another credit-fueled recovery, wherein the US consumer is, again, borrowing aggressively against a collateral base that is ‘defined’ by paper wealth, rather than ‘real’ income growth.

The stock market has replaced the housing market as that collateral base against which the US consumer is now borrowing hand-over-fist.

Yes, there are differences, the ”breadth’ of this ‘reflation’ is not the same as it was with the mortgage market debacle. Banks are (allegedly) not involved, with bank lending growth remaining less than overtly reflationary.

But the similarities are intriguing, if not somewhat frightening, as US households place massive bets, again, that the stock market is in a Nirvana-like, perma-bull market, and that ‘tapering’ is not a threat …

… just like US households placed massive bets that housing prices were incapable of deflating.

Not only that, but tapering has a major impact on the US bond market, with buyers having become increasingly scarce, against which the tide of supply does NOT recede for several years, if even then.

A rise in interest rates that has a negative impact on the US stock market would require another dose of monetary steroids, because the implications of a deflation in stocks would be too significant for the underlying macro-economy to handle.

To simplify, the unwritten mandate of the Fed is now singular; to prevent the stock market from failing.

The greater fear stems from thoughts that the macro-market dynamic has been internally ravaged by years of steroid abuse, and anything less than an increase in ‘roid’ dosage from the Fed may lose its effectiveness in fighting macro-muscle atrophy.

We could say we see evidence of this already, in the expanding and recently developed divergences exhibited within the overlay chart on display below.

Notice how Gold led the charge into QE-II, peaked first, and rolled over first, breaking down, and plunging amid disinvestment and a rotation out of safety, and into risk assets.

Next it was Home Prices, peaking, and most recently … breaking down.

We could add Emerging Market stock indexes, Emerging Market Bond prices, Emerging Market currencies … and … the CRB Index … all of which have followed Gold to the downside, in a GLARING example of the ‘internal atrophy’ taking place, as per the global market’s narrowing response to Fed QE.

Subsequently, we theorize that there is significant risk associated with tapering, particularly when tapering turns into ‘tapping out’, when the Fed reaches the point where they are no longer buying-to-accumulate any assets. There is risk that ‘extends’ to the stock market, for its tight, reliant relationship with the Fed’s Balance Sheet (our detailed “Fourteen-For-Fourteen” digs deeper into this dynamic, with specific ‘predictions’ for the path of the S+P 500 in 2014, based on the pace of tapering).

But more pointedly the risk emanates from the potential impact on US Treasury Bond and Note yields, as a result of an eventual ‘tap out’ by the Fed.

We find it most interesting to observe the overlay chart below in which we plot the Fed’s Assets Held Outright (black line) versus Custody Holdings (foreign official holdings of US Treasury securities, red line). We first focus on the rise in the Fed’s Balance sheet associated with QE-III, during which time bond and note yields in the US have risen.

Secondly, and most importantly, we shine the spotlight on the peak in Custody Holdings, and the DECLINE in 2013. For sure, it is NOT a coincidence that foreign officialdom turned NET SELLERS of US Treasuries in May, precisely on the back of Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s first mention of ‘taper’.

Demand from foreign officialdom is flat, at best.

The US ‘public’ is not buying bonds.

The US ‘public’ has followed the lead of the Pied Piper Ben Bernanke, the monetary maestro, who has carried the day on his back with some spectacular flute playing, calming the masses, resurrecting confidence, and facilitating a rotation out of safety (bonds, gold) and back into risk assets, stocks specifically.

So, from where will the marginal buyer of US Treasury bonds appear ??

No doubt, there is NO dearth of supply.

We examine the ‘schedule’ of ‘Treasury Obligations’ seen below.

Need we say more ??

A tsunami of Treasury supply, no matter how you slice-and-dice it.

And the Fed is potentially, probably, pulling the plug on a half-trillion a year in ‘support’??

Moreover, that ‘support’ which is to be removed represents pure monetization, actual evaporation of debt (for all intents and purposes).

Tapering to a ‘tap-out’ also means more supply in ‘perpetual roll-over’.

Over the next five-years, that is virtually $2.5 trillion.

When we add the new debt, needed to finance this year’s (fiscal) deficit, well the numbers start to add up very quickly. Yes, seeing the annual US deficit ‘shrink’ (laughter) by half, from $1 trillion, to something closer to $500 billion, could be labeled ‘improvement’. But, just five years ago the current deficits would have been record breaking, and still represent a significant, on-going, supply side issue.

So, who is the ‘marginal’ buyer of US debt ?? Who will help maintain ‘equilibrium’ to where Treasury yields will not rise ??

From a simple supply-demand dynamic, the risk-reward skew is to the upside in bond yields.

Of course things are never simple.

Especially in the Breaking Bad Era, where BAD is GOOD !!!

Evidence last week’s US payroll data … and the hundreds of thousands of chronically unemployed who simply fell out of the ‘equation’. This alone speaks volumes to the dysfunction in the US labor market.

But still, even during any initial ‘positive’ reaction to the ‘negative’ news, we might offer a thought: any macro-economic deflation that is deep enough to sway the Fed, will also have an impact on the fiscal side of this dual-headed coin … most probably towards increased bond supply.

Yet still, some might hypothesize that there is a major difference now, than during the housing-credit-deflation induced event of 2008-09, the banking system was saved, and is now solid.

As evidenced, of course, in this new era … by rising bank share prices.

For sure, banks are more ‘liquid’.

No debate.

Thanks to the Fed, and the Fed only, as is clear upon a survey of the overlay chart below revealing the link in Bank Balance Sheets, a distinctively direct link … to the Fed’s Balance Sheet.

And while bullish for the bank shares, this dynamic is not ‘positive’.

Indeed, only in the ‘Breaking Bad Era’ could this be construed as ‘positive’. But it is not positive, not when it means banks sit on their own mountain of ‘cash’ (aka, US Treasury securities), instead of lending that money.

Moreover, with huge holdings of US Treasuries, In the advent of another deflationary wave banks could well turn net sellers of government debt.

In other words, do not look to US financial institutions to plug any hole that might develop in the US bond market.

Another, less obvious reason that we say the rise in ‘cash’ held by banks is not ‘positive’, has to do with what is happening in the background with Bank Balance Sheets. The level of cash-securities held by US Commercial Banks, about $2.7 trillion, is peanuts compared to the level of risk banks are carrying in terms of ‘Derivative Holdings’.

In fact, as we try to comprehend the figures shown in the chart below, extracted from the FDIC’s Quarterly Banking Profile’s breakdown of Commercial Bank Balance Sheets … we are continually shocked.

Shocked to think that during this period of Fed largesse, during this period where the banks are allegedly healing as they do dispose of some non-performing assets … the risk is rising again, and rising rapidly.

Most troubling is the fact that the vast majority of the rise in, and the total of, Derivative holdings, roughly $225 trillion, yes trillion, are labeled as Derivatives Held for “Trading Purposes”, as opposed to being held for “Hedging Purposes’.

Indeed, it appears that risk and leverage in the banking system is still alive and well. No wonder the biggest banks, who hold the lion’s share of the derivative risk, now carry the moniker of ‘too big to fail.

They are called that because they are, literally … “too big” … specifically as it applies to their holdings of Derivatives for Trading Purposes (again, pegged at $225 trillion).

The simple fact that in the twelve-months ending June-2013 (data release lagged by the FDIC, one reason it goes largely unnoticed), Bank holdings of Derivative contracts linked to ‘trading'(aka profit generation) rose by more than $11 trillion …

… which dwarfs the expansion in Bank cash holdings …

… dwarfs the expansion in Bank Deposits …

… and, even more ‘tellingly’, dwarfs the expansion in the Fed’s Balance Sheet, over that same period, by about ten-to-one.

And most acutely frightening is the fact that the expansion in derivative exposure is most focused in Fixed-Income derivatives, by far, as seen below ($188.3 trillion, yes, trillion, in Fixed-Income contracts alone).

Clearly, the Fed is walking a tightrope.

Again, in our view, the risk-reward skew in the US Treasury market, for 2014, is tilted towards rising yields, which points us in the direction of strategies that accept that premise.

In our “Fourteen-For-Fourteen” we offer an even more detailed look at the US Treasury market specifically, from a technical perspective, and a strategic perspective.

We also take a closer look at the US consumer, household net worth, retail sales, and even gasoline prices, as factors that will play into the US based theme during 2014.

And that, is just our first of fourteen major macro-market themes for 2014, which encompass more than 200 pages of charts, graphs, and data slides covering both fundamental and technical analysis.

It is with a heartfelt thank-you that I nod in the direction of my colleague and conference-golf buddy John Mauldin; the man behind the curtain, Ed D’Agostino; the gang at Mauldin Economics; and my Kiawah Island golf buddy Grant Williams, for their willingness to participate with us in offering this preview of our 2014 Outlook.

Our fourteen market themes for 2014 include careful examinations of the monetary policy challenges faced by multiple Central Banks’ and the potential impact on the bond, FX and stock markets (including Exchange Traded Funds).

We also highlight some very specific currency challenges in some key regions especially as it relates to devaluations and competitive depreciation, and how that will impact the global markets. And, we shine the spotlight on a few very specific metals and energy opportunities with some compelling market charts and inter-market analysis.

Finally, we offer a few commodity plays in line with their underlying supply-demand fundamentals, including focus on the parallel opportunities within the commodity ETN universe.

All fourteen themes have been produced as separate chapters in video form (and come with a printable pdf version), all of which include detailed market charts and audio commentary.

ACT NOW to get all Fourteen Macro Themes at a special discounted rate (over 15% off) for readers of John Mauldin’s Outside the Box.

SEND $249.99 to [email protected] via www.paypal.com

Or email [email protected] and get special access now.

Like Outside the Box?

Sign up today and get each new issue delivered free to your inbox.

It’s your opportunity to get the news John Mauldin thinks matters most to your finances.

© 2013 Mauldin Economics. All Rights Reserved.

Outside the Box is a free weekly economic e-letter by best-selling author and renowned financial expert, John Mauldin. You can learn more and get your free subscription by visiting www.MauldinEconomics.com.

Please write to [email protected] to inform us of any reproductions, including when and where copy will be reproduced. You must keep the letter intact, from introduction to disclaimers. If you would like to quote brief portions only, please reference www.MauldinEconomics.com.

To subscribe to John Mauldin’s e-letter, please click here: http://www.mauldineconomics.com/subscribe

To change your email address, please click here: http://www.mauldineconomics.com/change-address

Outside the Box and MauldinEconomics.com is not an offering for any investment. It represents only the opinions of John Mauldin and those that he interviews. Any views expressed are provided for information purposes only and should not be construed in any way as an offer, an endorsement, or inducement to invest and is not in any way a testimony of, or associated with, Mauldin’s other firms. John Mauldin is the Chairman of Mauldin Economics, LLC. He also is the President of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC (MWA) which is an investment advisory firm registered with multiple states, President and registered representative of Millennium Wave Securities, LLC, (MWS) member FINRA, SIPC, through which securities may be offered . MWS is also a Commodity Pool Operator (CPO) and a Commodity Trading Advisor (CTA) registered with the CFTC, as well as an Introducing Broker (IB) and NFA Member. Millennium Wave Investments is a dba of MWA LLC and MWS LLC. This message may contain information that is confidential or privileged and is intended only for the individual or entity named above and does not constitute an offer for or advice about any alternative investment product. Such advice can only be made when accompanied by a prospectus or similar offering document. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. Please make sure to review important disclosures at the end of each article. Mauldin companies may have a marketing relationship with products and services mentioned in this letter for a fee.

Note: Joining The Mauldin Circle is not an offering for any investment. It represents only the opinions of John Mauldin and Millennium Wave Investments. It is intended solely for investors who have registered with Millennium Wave Investments and its partners at http://www.MauldinCircle.com (formerly AccreditedInvestor.ws) or directly related websites. The Mauldin Circle may send out material that is provided on a confidential basis, and subscribers to the Mauldin Circle are not to send this letter to anyone other than their professional investment counselors. Investors should discuss any investment with their personal investment counsel. You are advised to discuss with your financial advisers your investment options and whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs prior to making any investments. John Mauldin is the President of Millennium Wave Advisors, LLC (MWA), which is an investment advisory firm registered with multiple states. John Mauldin is a registered representative of Millennium Wave Securities, LLC, (MWS), an FINRA registered broker-dealer. MWS is also a Commodity Pool Operator (CPO) and a Commodity Trading Advisor (CTA) registered with the CFTC, as well as an Introducing Broker (IB). Millennium Wave Investments is a dba of MWA LLC and MWS LLC. Millennium Wave Investments cooperates in the consulting on and marketing of private and non-private investment offerings with other independent firms such as Altegris Investments; Capital Management Group; Absolute Return Partners, LLP; Fynn Capital; Nicola Wealth Management; and Plexus Asset Management. Investment offerings recommended by Mauldin may pay a portion of their fees to these independent firms, who will share 1/3 of those fees with MWS and thus with Mauldin. Any views expressed herein are provided for information purposes only and should not be construed in any way as an offer, an endorsement, or inducement to invest with any CTA, fund, or program mentioned here or elsewhere. Before seeking any advisor’s services or making an investment in a fund, investors must read and examine thoroughly the respective disclosure document or offering memorandum. Since these firms and Mauldin receive fees from the funds they recommend/market, they only recommend/market products with which they have been able to negotiate fee arrangements.

PAST RESULTS ARE NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS. THERE IS RISK OF LOSS AS WELL AS THE OPPORTUNITY FOR GAIN WHEN INVESTING IN MANAGED FUNDS. WHEN CONSIDERING ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS, INCLUDING HEDGE FUNDS, YOU SHOULD CONSIDER VARIOUS RISKS INCLUDING THE FACT THAT SOME PRODUCTS: OFTEN ENGAGE IN LEVERAGING AND OTHER SPECULATIVE INVESTMENT PRACTICES THAT MAY INCREASE THE RISK OF INVESTMENT LOSS, CAN BE ILLIQUID, ARE NOT REQUIRED TO PROVIDE PERIODIC PRICING OR VALUATION INFORMATION TO INVESTORS, MAY INVOLVE COMPLEX TAX STRUCTURES AND DELAYS IN DISTRIBUTING IMPORTANT TAX INFORMATION, ARE NOT SUBJECT TO THE SAME REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS AS MUTUAL FUNDS, OFTEN CHARGE HIGH FEES, AND IN MANY CASES THE UNDERLYING INVESTMENTS ARE NOT TRANSPARENT AND ARE KNOWN ONLY TO THE INVESTMENT MANAGER. Alternative investment performance can be volatile. An investor could lose all or a substantial amount of his or her investment. Often, alternative investment fund and account managers have total trading authority over their funds or accounts; the use of a single advisor applying generally similar trading programs could mean lack of diversification and, consequently, higher risk. There is often no secondary market for an investor’s interest in alternative investments, and none is expected to develop.