It has been a long week.

I am hopeful that an optimistic Friday close – or better yet, some time with family and (er, appropriately small) groups of friends – has allowed you to put some of it in perspective.

I suspect that perspective won’t be entirely pleasant. Yes, realizing that those we love are what matter may assuage the anxieties of one of the most volatile weeks in US financial markets history. But it also means that a lot of the real anxiety, frustration and pain is still ahead of us. We are on the front end of whatever Covid-19 curve we end up experiencing. At long last, we are making plans to look more like Singapore and less like Italy, but the speed, competence and consistency with which we execute those plans will determine whether that is, in fact, what we experience. We aren’t ashamed to say we think this will prove to be our finest hour.

I am less sure that this will prove to be our finest hour as investors. I don’t mean returns, although most of us are bleeding. I don’t mean undue fear and greed behaviors, although many of us are demonstrating them. I mean that I fear investors are thinking about their gameplans today in ways that could damage their outcomes over long horizons. Unfortunately, the worst of these frameworks are being actively promoted by market missionaries in financial media and academia.

Sometimes at the same time.

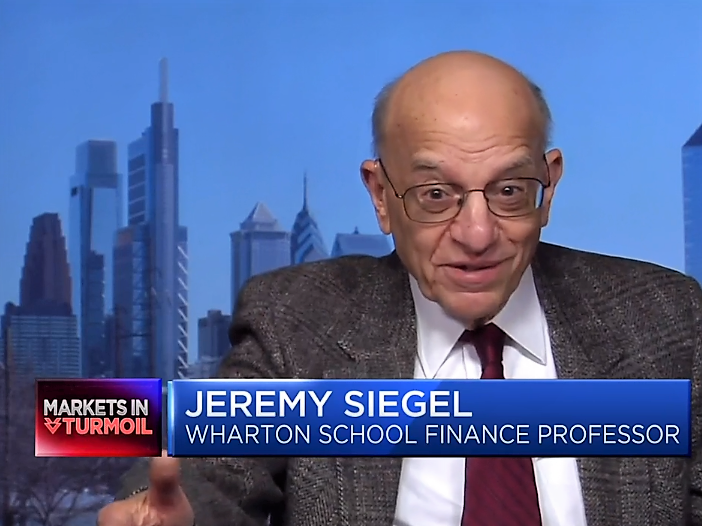

Jeremy Siegel has taught Finance 101 at Wharton for a long time. Not “taught it to Donald” long, but certainly “taught it to Ivanka” long. The course is more along the lines of a monetary economics class there, but the man has trained bankers and PE guys to put together DCF models for decades. And that’s fine. Really. What is less fine is that Siegel, like many other academics, has found additional sources of revenue and book sales by applying the bottom-up thinking about company-level cash flows to CNBC on-air macro commentary.

The result is often very much like the below, which I extracted from an on-air interview on March 2.

“I’d like to first repeat what I said last week, and that is that over 90% of the value of a stock is due to its profits more than one year into the future. So as bad as this year can be…we could really have a short quick recession, the long-term value is not significantly impaired…let’s face it, this is mostly going to be a demand-induced slowdown.”

Dr. Jeremy Siegel to CNBC (March 2, 2020)

If you watched CNBC at all the last couple weeks, you probably heard variants of this prediction. “How much should valuations really drop if they only impact two quarters of EPS? Even if we lost a WHOLE year, it would be irrational for stocks to go down by more than 10%!” It is comforting, rational-sounding and calm. Professorial, if you will.

It is also utter hogwash.

I am absolutely NOT saying that investors shouldn’t build investment philosophies around the judgement-based valuation of cash flow streams. The raison d’etre for this entire website is the belief that this is still what investing ought to mean, that our efforts should be focused on reinforcing the primary intended function of markets as the appropriate pricing and direction of capital! I AM saying that treating the markets like a first-year banking analyst at Morgan Stanley – organizing a model completely around a single key variable – is a recipe for tunnel vision on that variable to the detriment of a million other things that matter. Not just things over some short, ‘irrational’ period – I’m talking about things that really matter to asset prices and returns over extended periods.

This behavior makes one blind to all sorts of things.

The first blind spot, as we have argued in more detail in our institutional research, is that it treats uncertain events – items of unknowable incidence and severity – as if they were risks that could be estimated probabilistically. Even if we remain in purely fundamental space, there are specific facts about the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on cash flows which utterly confound probabilistic estimation. Will its future mutations prove yet more virulent? Will challenges in vaccine efficacy for those strains make an endemic coronavirus a transformational, recurring long-term issue? Will summer heat in the northern hemisphere kill it nearly to the ground? Will governments conjure epic, MMT-level stimulus response? How quickly will governments work to implement and enforce aggressive mitigation measures? How far along the exponential curve are we actually today given our systematic undertesting?

These thoughts shouldn’t paralyze you, although the fact that they each contain embedded series of uncertain and dependent outcomes of potentially significant magnitude should absolutely influence your active risk budget, portfolio concentration and use of leverage! Yet this is not an inherently bearish argument. The veil of uncertainty contains both uproariously positive and fiendishly negative series of events.

The problem is that analyzing these events and their effects probabilistically isn’t hard. It is impossible. Yet the machinery of our industry cannot go into quarantine. It must produce research! It must produce estimates! It must produce predictions! How does it do it?

It picks a reasonable-sounding central assumption, then shows that even if you doubled it, things would still fit within your estimation range.

The second blind spot still sits within the world of pure fundamentals, and is exposed to both uncertainty and risk. It is the tendency to underestimate the length and magnitude of chains of dependent events. Estimating how 2-6 months of a global cratering of demand and interruption in supply will manifest in knock-on effects is hard. Really hard. Assuming that you’re going to capture those knock-on effects by applying a low baseline demand shock estimate on EPS is ludicrous.

It IS easy enough to think in advance of some anecdotal examples to illustrate this, even though handicapping them today is a practical impossibility (in large part because they are dependent on binary assumptions about key policy actions). Even without going into the availability of credit and other primary capital markets, there is a lot to consider.

Let us say that the crisis in air travel places a major domestic airline in financial distress. Now assume that the government does not bail them out. It goes through some kind of BK or liquidation. What if they had accounted for 60% of the travel capacity of a half-dozen medium-sized cities? 100% of the economics of two dozen local mechanical and aerospace services companies? What of their replacement parts contracts and those 25 A320s they have on order?

Alternatively, take a look at the data published by OpenTable on daily restaurant activity across major markets (mostly in North America).

What happens if and when the 50% drop we see on Thursday of this week in some markets becomes the story in every town and city in America for the better part of two months? If your average local restaurant grosses $10,000-15,000 a week and operates on a sub-10% margin, how long until they have to stop paying the waitstaff and line cooks? How long until the credit line with the First Community Bank of Podunk runs dry or gets pulled? When they stop paying rent, how long until the local businessman who owns their building is forced to pull capital earmarked to fund the growth of his valve-fitting shop to service the debt he used to buy it? How does that impact the growth and returns of the small factory in the region that had counted on their order being delivered on time?

And how long do these types of effects ripple through multiple businesses and multiple industries?

What happens to consumer behaviors after a month or two of social distancing? After a month or two of adapting to a life without available daycare? After a month of effectively homeschooling children? Is there a tranche of the public that remained loyal to local brick-and-mortar retail for some category of their consumption that will undergo a permanent transition to online shopping? Do consumption patterns change permanently in other ways?

And what of tourism? How long do tourists eschew Covid-19 hotspots? Cruise ships? Casinos? Ride-sharing? Will ALL the fashion and real estate and investment conferences that huddle in Milan come back in 2021? How long will the overhang on tourism more generally last? Will tourists shy away from Thailand, Cambodia and Belize, countries heavily dependent on tourism? If they do, how long can those industries hang on before capital flees to other endeavors, domestic or otherwise?

If and when we flatten the curve, and Covid-20 pops up in the winter, how reflexively and violently do briefly allayed fears shift behaviors back to the state we know today?

Again, please do not see this as inherently bearish relative to current prices. Let me take the other side of this.

What if many of the companies and industries that die were negative ROI, good-capital-after-bad companies and industries that probably should have died long ago, but for the sweet succor of interventionist government? What if the forced utilization of remote work technology finally becomes truly transformational, permanently reducing the operating expenses and capital requirements of a dozen industries? What if the federal stimulus in the US and elsewhere results in rapidly expanded networking infrastructure investments across secondary and tertiary cities to support it?

The point, again, is not that we should allow ourselves to become overwhelmed by the range of potential outcomes or the fact that many of them simply cannot be predicted. It is to recognize that the effect of events on other events at times like this is to make fools of forecasts built on some expectation of cash flows over a defined period. That’s why (thankfully) actual fundamental investors taking risk in equity markets have been busy exploring, such as they can, questions like all of the above for the last few weeks. That’s why they’ll continue to do so, no matter how many two-quarter-shock-to-the-ol-DCF cartoons get trotted out to pump up stocks.

The “10% of NPV!” approach also creates a blind spot to a class of path-dependent effects which exist outside of pure fundamentals – that is, in the world of narrative. Consider, if you will, these declarations from important political missionaries across the political spectrum from the three most important economies in the world in only the last two days.

Like German Economic Minister Peter Altmeier.

Germany would like to localize supply chains, nationalization possible, minister says [Reuters]

Like Senator Ted Cruz.

Coronavirus Spurs U.S. Efforts to End China’s Chokehold on Drugs [NY Times]

Like Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeman Lijian Zhao.

Chinese diplomat accuses US Army of creating coronavirus epidemic in Wuhan [Washington Examiner]

Think this emerging narrative of global decoupling and deglobalization is isolated to healthcare and pharmaceutical supply chains? Tell that to US Senator Marco Rubio.

And to the think-tanks who are already furiously spinning out pro-autarky thinkpieces in recognition of the rapidly changing zeitgeist on international trade links.

Make America Autarkic Again [Claremont Institute]

I suspect that Ben and I are both going to be writing a lot more about the de-globalization narrative as it emerges. I can’t tell you today how probable it is that any one company or industry will move more production back to domestic shores. I can’t tell you how probable it is that regulation will be put forward in this administration or the next to force (explicitly or implicitly) some of this to take place. I can’t tell you how that will impact cost structures and corporate margins. I can’t tell you how that will impact the expectations and multiples investors are willing to pay, or their home country bias, or countless other dimensions of the collective determination of asset prices. I can’t tell you if this is long-term bullish or bearish…OK, probably a little bearish.

I CAN tell you that if your analysis of market and prices is completely abstracted from the path of events that could lead to a significant movement toward global economic decoupling, you’ve got blinders on. And if you think applying “conservatism” to widen the range of your best guess at a deterministic period hit to EPS is the right way to accommodate its potential, you’ve lost the plot completely.

Cartoons constructed from deterministic EPS macro analyses have one more trick to play on us. Only this one isn’t about blinders on the future. It’s about blinders on the past.

Buried in the sour grapes responses some on the buy side and in the financial adviser community have had to the (IMO pretty subdued) victory laps from bearish funds and traders is a seed of really dangerous thinking. Paraphrasing from a half dozen or so, the claims go something like this: “None of these bears predicted a pandemic. This bear market is the result of the pandemic, so the people who are short because they thought the market was expensive or being propped up by the Fed or whatever reason they were always bearish don’t get credit for getting it right.”

I’m not linking to specific people here for a few reasons. First, a lot of people are publishing things like this in letters and I don’t want to single anyone out. Especially because I believe most of them are perfectly smart, good people trying to do right. Second, it’s hard to deal with being down this much in a rough couple weeks, and I’m empathetic to the annoyance. Third, there are absolutely people who have been really bearish for a very long time and are STILL underwater for their investors. They still have a lot to prove before they have any business claiming to be right.

But the sentiment is still wrong. Really, really wrong.

Look, of course just about everybody involved in markets in any active sense is responding to the impact of Covid-19 and the broad economic impact of our global mitigation effort. But for all of us who are in the business of investing, we must understand this: asset returns are never just a mechanistic reflection of changes in forward-looking estimates of some fundamental thing. They are also a reflection of inertia. Of path-dependence.

The fact that a stock traded at a particular multiple today is often as much (and in many cases far more!) driven by the fact that it traded at that multiple yesterday as it is by the market’s aggregated expectations of future growth and appropriate discounting of those expectations. When the market declines sharply in response to some suspected (or in the case of Covid-19, obvious) proximate cause, do you not think that some investors who deemed yesterday‘s price appropriate in part because of expectations of asset price-motivated central bank activities or the expectation of unduly growth-hungry or yield-hungry behavior by other investors calibrated their actions today to consider how those other factors might be affected, too?

Investing in ways that reflect a belief that asset classes have embedded inertial assumptions (like say, multiples) but with uncertainty about a catalyst for changing them is not unusual at all. It’s the basis for a huge swath of classic investment strategies! Uh, value? Even when we feel like the catalyst of market action is plain, believing that the magnitude of the market’s response to it is wholly related to that catalyst and not the catalyzed reexamination of other factors will not lead to a useful forward-looking analysis of positioning.

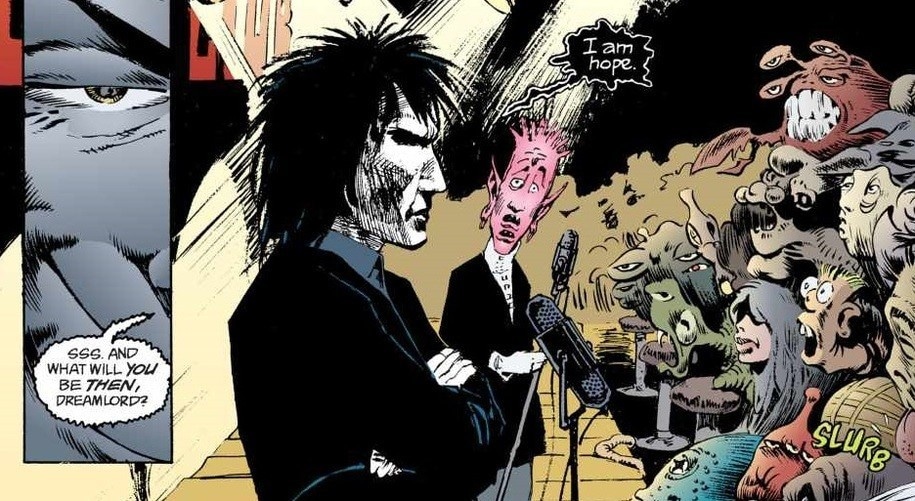

When Ben and I went independent back in 2018, one of the first things he wrote was the Things Fall Apart series. In the third installment, he focused on distinguishing between the big recurring macro risks faced by investors, and one big unknown. He used the example of the Oldest Game from the marvelous Neil Gaiman’s Sandman to illustrate the difference in kind – not magnitude – of accommodating uncertainty in our investment frameworks.

The Oldest Game is a clever construction in which two players in turn conjure identities capable of defeating the identity selected by the other player on his prior turn.

There are many ways to lose the Oldest Game. Failure of nerve, hesitation, being unable to shift into a defensive shape. Lack of imagination.”

Neil Gaiman, from Sandman

The structurally bullish will warn us against failure of nerve. The traders will warn us against hesitation. The structurally bearish will warn us about being unable to shift into a defensive shape.

What we should be worried about is a lack of imagination.

I know it feels like you are sitting in your home office in the middle of a pandemic quarantine, because you probably are. But you are also sitting in the middle of a period of historic change and upheaval. Do you think that it is possible that an almost complete shut-down of many forms of trade, tourism, travel, retail activity for 1-2 quarters or MORE will not result in some kind of transformation? Of consumer behaviors? Of regional industry? Of local industry? Of investor preferences? Of the shape of globalization?

Take off the blinders and LOOK.

Or better yet, do what the winner of the Oldest Game did.

Choronzon: I am anti-life, the beast of judgement. I am the dark at the end of everything. The end of universes, gods, worlds… of everything. Sss. And what will you be then dreamlord?

Dream: I am hope.

Sandman, by Neil Gaiman

The people who win THIS game (and the people who help us ALL win the bigger game) aren’t going to be the ones wasting ink raining on the parade of so-called ‘perma-bears’. They aren’t going to be the ones putting together pseudo-empirical analyses for their fund investors explaining what happened in the subsequent 5 1/2 week period in 17 out of the last 28 drawdowns of 20.49% or more. The people who win this game will be the ones who can smile at the end of universes, gods and worlds and say, “I am Hope.”

That doesn’t mean being bullish.

It means having imagination.

Imagination to see with clear eyes the shocking capacity of uncertainty to embarrass probabilistic frameworks used incorrectly to model it.

Imagination to see with full hearts how vast the range of paths and outcomes can be when they are dependent on the path of critical, potentially transformational events.

Like it or not, you live in interesting times. Don’t waste them on a lack of imagination.

It is my sincere desire to provide readers of this site with the best unbiased information available, and a forum where it can be discussed openly, as our Founders intended. But it is not easy nor inexpensive to do so, especially when those who wish to prevent us from making the truth known, attack us without mercy on all fronts on a daily basis. So each time you visit the site, I would ask that you consider the value that you receive and have received from The Burning Platform and the community of which you are a vital part. I can't do it all alone, and I need your help and support to keep it alive. Please consider contributing an amount commensurate to the value that you receive from this site and community, or even by becoming a sustaining supporter through periodic contributions. [Burning Platform LLC - PO Box 1520 Kulpsville, PA 19443] or Paypal

-----------------------------------------------------

To donate via Stripe, click here.

-----------------------------------------------------

Use promo code ILMF2, and save up to 66% on all MyPillow purchases. (The Burning Platform benefits when you use this promo code.)

That face.

Every time.

What’s his name again?

Bugsy?

Very long article to say “I am long, I am bleeding, I hope ration behavior returns, I have based by entire career on ration thinking”

Sorry, it’s not going to work in this time frame, you should have left the market on the 1st 1000 point day drop, because it is no longer a working market that allocates capital, it is a CASINO, driver by fear, and the heard has panicked.