“People crave trust in others because God is found there.” [Dom de Bailleul]

After a meeting with General Gordon of Khartoum in South Africa in 1881, Cecil John Rhodes set up a secret society, to establish a New World Order. The society, disciplined on Jesuit-style lines, became Rhodes’s lifelong obsession, and after his death, it lived on and grew under the leadership of his executor, Lord Alfred Milner.

In the book, The Secret Society of the Elect, Robin Brown unpacks this astonishing and largely unknown history. Ranging from the diamond mines of Kimberley to the halls of power in Westminster, and peopled with characters such as Olive Schreiner, Princess Radziwill, Kaiser Wilhelm, and David Lloyd George. This book is a page-turner that will make you see the world, both past and present, in a different light. It might explain where the current concept of a ‘World Government’ came from and Britain is at its root! [Edited extracts from Encyclopedia Britannica follow]:

Early struggles and financial successes. Rhodes was the son of the vicar of Bishop’s Stortford, and the family’s roots were in the countryside, where Cecil Rhodes always felt at home: tree planting and agricultural improvement were among his lifelong passions, though his earliest ambition was to be a barrister or a clergyman.

His father was prosperous enough to send one son to Eton College, another to Winchester College, and three into the army. Cecil, however, was kept at home because of a weakness of the lungs and was educated at the local grammar school. Poor health also debarred him from the professional career he planned. Instead of going to the university, he was sent to South Africa in 1870 to work on a cotton farm, where his brother Herbert was already established.

The farm in Natal was not a success. On his arrival, Rhodes found that his brother had already left for the diamond fields of Griqualand West. Although Herbert returned to the farm, and the two brothers continued stubbornly trying to grow cotton for a year, the “diamond fever” eventually overcame them.

In 1871 they moved to Kimberley, the centre of mining, where life was even harder than in Natal. Herbert was restless and stayed only until 1873, but Cecil’s characteristic determination kept him at Kimberley off and on for years.

For eight years, until he took a belated degree in 1881, he divided his life between Kimberley and Oxford. Both societies found him odd, though he did his best to conform outwardly to the conventions. At Oxford, his eccentric habits, falsetto giggle, rambling monologues, and unusual background intrigued the younger students around him. So did his philosophy of an almost mystical imperialism.

He gradually advanced from being a speculative digger to the status of a man of substance with ambitious ideas on the future of the diamond industry. His first partnerships were with young men as impoverished as himself, such as C.D. Rudd, with whom he formed De Beers Mining Company (1880); so called after the De Beers mining claims, many of which he had acquired.

Eventually, success brought new friends and also rivals. Alfred Beit, a German who knew the diamond market intimately, was his most valued friend. With Beit’s help, Rhodes expanded his claims until all the De Beers mines were under his control. In 1887 he set about acquiring the Kimberley Central Diamond Mining Company, which was mainly controlled by Barney Barnato. A furious competition to buy up shares ended in Rhodes’s favour in 1888 and Barnato agreed to merge his company with Rhodes’s company, forming De Beers Consolidated Mines, Ltd.

However, several minor shareholders in Barnato’s company were not in favour of the planned amalgamation and tried to halt the merger in court, which was found in favour of the shareholders. To work around the ruling, Barnato and Rhodes, who then controlled most of the shares in Kimberley Central, liquidated the company. De Beers Consolidated Mines, Ltd., then purchased Kimberley’s assets for more than £5 million ($25 million), which was paid out, in part, to the aggrieved shareholders.

Other lesser mines also fell under Rhodes’s control, until by 1891 De Beers Consolidated Mines, Ltd., owned 90% of the world’s production of diamonds. He also acquired a large stake in the Transvaal gold mines, discovered in 1885, and formed the Gold Fields of South Africa Company in 1887. Both Rhodes’s major companies had terms in their Articles of Association allowing them to finance schemes of northward expansion.

Rhodes never regarded moneymaking as an end in itself. “Painting the map red,” building a railway from the Cape to Cairo, reconciling the Boers and the British under the British flag, and even recovering the American colonies for the British Empire, were all part of his dream. With those ideas in view, he first went into politics in 1881, offering himself for election to the parliament of the Cape Colony in a constituency in which he had to depend on Boer support.

He held it for the rest of his life. Though unimpressive as a speaker and contemptuous of parliamentary procedure, he earned respect for his original views. He made friends with many Boer politicians, he espoused the cause of the native Africans in what was then Basutoland and Bechuanaland (now Lesotho and Botswana), and always he had his eyes fixed on the north.

His first intervention in native African policy came in 1882 when he was appointed to a commission to pacify Basutoland after a minor rebellion. The rebellion had been put down by the former British governor of the Egyptian Sudan, Gen. Charles Gordon, acting for the Cape government.

Gordon had succeeded, not by force but, by organising discussion meetings with the tribal chiefs. Rhodes was impressed by the man and his methods, though less favourably by the contempt that Gordon showed for financial reward.

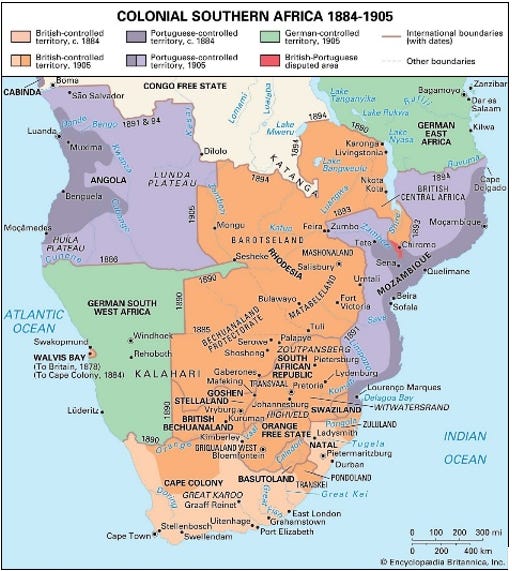

His determination to keep open a road to the north involved him in many disputes. Other imperial powers—the Germans, Belgians, and Portuguese—competed for the uncharted interior of Africa, as were the Transvaal Boers. The missionaries were, in Rhodes’s view, overly solicitous of native African interests; the Cape government was weak; and the British government, which he called the “imperial factor,” was too distant to understand his ideas. But he assiduously cultivated the government’s representatives in Cape Town—particularly the high commissioner Sir Hercules Robinson—with profitable results.

Mineral wealth, communications, and, eventually, white settlement were his objectives. All the boundaries were unsettled, however, and many intrusions had to be frustrated first. Boers from the Transvaal, trying to annex slices of Bechuanaland, proclaimed two small independent republics in Stellaland and Goshen.

In 1882 a boundary commission, to which Rhodes again secured appointment, was sent to settle the boundaries of Griqualand West. Rhodes persuaded the commission to extend its mandate to the two small republics. In 1884, when the Germans in South West Africa (now Namibia) declared a protectorate over two territories (which, along with Stellaland and Goshen, would have sealed off the Cape Colony from the north), he persuaded the high commissioner that the British government must intervene. By the London Convention of 1884, the two republics were excluded from the Transvaal, and the Cape government agreed to help finance a protectorate over Bechuanaland.

His settlement of the Bechuanaland question was also soon threatened, for the deputy commissioner in the new area antagonised the Boers. Rhodes insisted on his removal and was appointed in his place. He succeeded in conciliating the Boers of Stellaland but could not prevent Paul Kruger, president of the Transvaal, from declaring a protectorate over Goshen, from which he withdrew only after an expeditionary force was sent up from the Cape.

A conference to settle the matter was held in February 1885 on the Vaal River, where Rhodes and Kruger met for the first time. Those two stubborn men, each determined to dominate Africa, each ever ready to quote Scripture for his purpose, naturally failed to achieve any meeting of minds.

Although Kruger was forced to give up Goshen, Rhodes did not get everything his way. It was decided that southern Bechuanaland should become a crown colony and northern Bechuanaland a protectorate. Rhodes, who wanted both annexed by the Cape Colony, resigned in protest in March 1885 and thereafter devoted strenuous efforts, both in Cape Town and London, to securing the transfer of the colony to the Cape.

Two men still stood in the way of Rhodes’s plans for developing the north. One was Kruger, with his policy of “Africa for the Afrikaners”—the Boers. By the Franchise Law of 1890, he denied political rights to the Britons and other foreigners (Uitlanders) who had come to work the gold mines in the Transvaal. He also tried to extend Boer control to Mashonaland and Matabeleland.

The ruler of the Matabele (Ndebele) was King Lobengula, Rhodes’s second obstacle. Kruger had approached him for a treaty and mining concessions in 1887, and so had many others. Lobengula, however, knew that once he let the white men in, he would never see their backs. The only white men he trusted were missionaries, and Rhodes duly found in John Moffat, the son of a famous missionary, a man to serve his purpose.

Once Moffat, as assistant commissioner for the crown colony of Bechuanaland, had, in February 1888, persuaded Lobengula to sign an exclusive treaty of friendship, Rhodes sent three of his trusted agents to obtain a mining concession based on the treaty. The concession was extracted from the reluctant Lobengula in October 1888.

To the last, he hoped he had only allowed the white man to dig “a big hole.” However, he had virtually signed away his kingdom, and Rhodes hastened to press the British government, through the high commissioner, to grant a charter to a new company, the British South Africa Company (BSAC), to develop the new territory. In October 1889 the charter was granted, and Lobengula allowed the digging to begin.

Queen Victoria found Rhodes’s imperialism attractive, no less than his courtly rebuttal of the accusation of being a woman hater: “How could I dislike a sex to which your Majesty belongs?” The upshot of his successful propaganda was that the charter granted by the British government went far beyond what Lobengula had conceded. There was no northern limit on it, and Rhodes intended to extend the chartered company’s control to Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and Nyasaland (now Malawi) as well as to the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now in Botswana).

In 1890 Rhodes’s Pioneers began their hazardous march into Matabeleland and thence to Mashonaland, where they established a fort in September to be called Salisbury after the British prime minister. In the following year, Harry Johnston took over the administration of Nyasaland in a dual capacity, as commissioner of the British government and an employee of the chartered company. Although eventually, the protectorate reverted fully to the British government, Rhodes’s influence was felt both north and south of the Zambezi River, and soon the new territories were called by his name.

These are the Policies of the prime minister of the Cape Colony of Cecil Rhodes. In the meantime, Rhodes had returned to office in 1890 in the only post big enough for him, as prime minister of Cape Colony. For five years he proved a successful and imaginative prime minister. He acquired a property called Groote Schuur, which he rebuilt in the Dutch colonial style and bequeathed as an official residence for future prime ministers of the Union of South Africa.

There, Rhodes lavishly entertained Dutch and British inhabitants of the Cape Colony and eminent visitors of all nationalities. Everything he undertook was on a massive scale. In parliament, he cultivated the support of the Afrikaner Bond without losing the goodwill of British liberals. His agricultural policies were sensible and effective. In native African policy he had to move cautiously. His Franchise and Ballot Act (1892) was passed, limiting the native vote by financial and educational qualifications.

The Glen Grey Act (1894), assigning an area for exclusively African development, was “a Bill for Africa,” as Rhodes proudly called it. In reality, it served to enforce segregation of native Africans, further disenfranchise them, and control their economic options. His main aim was to prevent the Dutch and British quarrelling over such policies. To him that involved the risk of “mixing up the native question with the race question.”

He also sought to unite the Boers and the British on his northern policy. The prospects were good because Kruger’s obstinacy alienated the Cape Dutch. To ensure that commercial traffic did not have to reach the Transvaal through the Cape Colony, Kruger had built a railway to Delagoa Bay.

Then in 1894, he closed the “drifts,” or fords, of the Vaal River to prevent the transport of goods by wagon, besides imposing heavy duties on Cape produce. Rhodes went to the Transvaal capital to protest but in vain. Kruger was compelled to yield only after a declaration by Rhodes’s attorney general that he was in breach of the London Convention, coupled with a threat by Joseph Chamberlain, who had become British colonial secretary in 1895, to support a military expedition.

Rhodes’s patience had begun to wear thin even earlier, partly because he knew his health was precarious and partly because he learned that the gold deposits of the Transvaal were enormous, whereas those of Mashonaland were proving poor. His northern policy was encountering unexpected frustrations.

The chartered company was in financial difficulties, its resources being overstretched. Although Rhodes’s agents secured some new territories for the company, elsewhere he was forestalled. An Anglo-German agreement of 1889 gave a strip of land to Germany, cutting off Bechuanaland from the north. The Belgian king Leopold II anticipated Rhodes by laying claim to Katanga (1890). The Anglo-Portuguese Convention of 1891 ended his hopes of eliminating Portugal from Africa.

Harry Johnston proved uncooperative in administering Nyasaland. When Rhodes paid his first visit to Rhodesia in 1891, he found the pioneers in an angry mood; to pacify them, he helped them generously out of his pocket. Serious trouble broke out in 1893, when Rhodes’s close friend the BSAC administrator, Leander Starr Jameson, instigated an invasion into Lobengula’s Matabeleland under dubious pretences.

A short sharp war ended in the total defeat of Lobengula and led to his death shortly thereafter, and pioneers streamed into Matabeleland. Rhodes was then at the pinnacle of his achievement, but the wider union of southern Africa continued to elude him. He was growing petulant and impatient and was visibly aging. By 1895 he was determined to settle accounts with the last obstacle, President Kruger.

There was already talk of using force to remedy the grievances of the Uitlanders in the Transvaal. The Uitlanders formed a National Union to support their cause, with Rhodes’s brother Frank among its leaders. Kruger sought the support of Germany, and in 1895 he again closed the drifts across the Vaal. Once more he was forced to withdraw, and by that time a conspiracy against him was under way. Rhodes knew about it and worked actively to foster it.

The effects of the Jameson raid on Rhodes’s career were crucial. Chamberlain was privy to the plan, but no one foresaw what resulted. The National Union in Johannesburg lost its heart and decided not to act. Rhodes, the high commissioner Sir Hercules Robinson, and Chamberlain all assumed that the plan had been called off, but Jameson recklessly decided to force the hand of the Uitlanders by invading the Transvaal on his own.

He launched the famous raid on December 29, 1895. It was a fiasco; his whole force was captured apart from a few killed. Rhodes was compelled to resign almost all his offices, not only in the Cape government but also in the chartered company, but he refused to denounce Jameson.

The raid was an almost complete disaster for Rhodes. Jameson and his colleagues were sent to prison, Kruger’s power was consolidated, the Dutch and British colonials were more deeply split than ever, and Rhodesia and Bechuanaland were taken over by the imperial government. Only the charter was preserved, and Rhodes spent the rest of his life promoting developments in the north. He even won public sympathy. His last years were full of disappointments, both personal and political.

Early in 1896, while Rhodes was in England, there was a serious revolt in Matabeleland. Rhodes returned by way of Egypt and took an active part in suppressing the revolt. He finally brought it to an end by holding a peace conference. On that occasion, Rhodes found the site in the Matopo Hills that he called the “View of the World” and chose it for his burial place.

His last years were soured by an unfortunate relationship with an aristocratic adventuress, Princess Radziwiłł, who sought to manipulate Rhodes and Sir Alfred Milner, the high commissioner in South Africa and the governor of the Cape Colony, and even Lord Salisbury, the English prime minister, to promote her ideas of the British Empire.

Rhodes was unused to scheming women, nor could the young bachelors surrounding him protect him from her. She forged letters and bills of exchange in his name and was finally sent to prison, but not before she had caused him much annoyance and scandal. In 1901, while he was in Europe, he was recalled to Cape Town to give evidence at her trial.

His last political act on his return was to support Milner in suspending the constitution of the colony until the South African War, which broke out in October 1899, was over. He was, however, already dying of an incurable heart disease. Before either the war or even Princess Radziwiłł’s trial was over, he died. His last journey through Africa in the funeral train to the Matopo Hills was a triumphal procession. Source Britannica Southern Africa: Cecil Rhodes in Southern Africa

Rhodes’s treaties with the various African chiefs tended to be of dubious legality, and he routinely pushed against or ignored established boundaries with other European colonial powers, which sometimes put him at odds with Britain’s Foreign Office. Some of the legislation passed while he was prime minister of the Cape laid the groundwork for the discriminatory apartheid policies of South Africa in the 20th century.

A legacy of a different nature was revealed when Rhodes’s Will was read in April 1902, detailing an imaginative scheme of awarding scholarships at Oxford to young men from the colonies and from the United States and Germany. That appealed to the public instinct for a more disinterested kind of imperialism.

Most of his fortune was devoted to the scholarships. As the Will forbade disqualification on grounds of race, many non-white students have benefited from the scholarships, though it is doubtful that such was Rhodes’s intention. He once defined his policy as “equal rights for every white man south of the Zambezi” and later, under liberal pressure, amended “white” to “civilised.” But he probably regarded the possibility of native Africans becoming “civilised” as so remote that the two expressions, in his mind, came to the same thing.

GOOD NEWS FROM SOUTH AFRICA

Tennis does a double take, and buying local is lekker! American Express has teamed up with ‘Tennis SA’ to develop the racquet sport, while celebs were all out on deck to back home-grown talent.

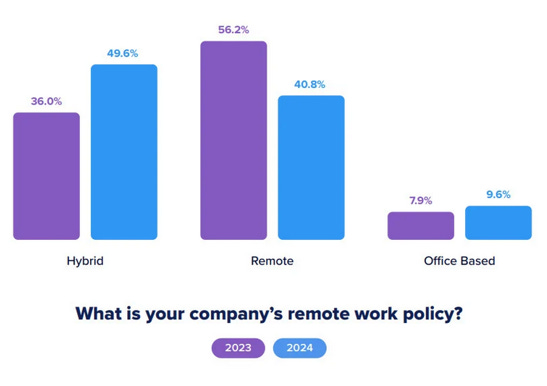

WORK FROM HOME(WFH) is here to stay! Employees in South Africa give the middle finger to the latest work-from-home shift.

FINALLY – AN OBSERVATION

NOTA BENE: On March 31, 2024, the Brits will put their clocks forward one hour, moving to BST (British Summertime), but nobody knows why! Now in SA, we are only one hour ahead of the UK. Time Zones are worth a look; I work globally so it is important for me when I log onto ZOOM or Skype.

COMING NEXT:

- The Financial Jigsaw Part 2 – Chapter 4 – “All Wars Are Now Bankers’ Wars” – Saturday March 30, 2024

- BOOM weekly global review – Tuesday, March 26, 202

- Letter from Great Britain – VLAD the LAD – Saturday, April 6, 2024

REFERENCES

- My Book: “The Financial Jigsaw” Parts 1 & 2 Scroll: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358117070_THE_FINANCIAL_JIGSAW_-_PART_1_-_4th_Edition_2020 including regular updates.

- BOOM Finance and Economics Substack (Subscribe for Free) – also on LinkedIn and WordPress. Plus Covid Medical News Network CMN News and BOOM Blog — All Editorials (over 5 years) — BOOM Finance and Economics | Designed for Critical Thinkers — UPDATED WEEKLY (wordpress.com)

“That life is worth living is the most necessary of assumptions, and were it not assumed, the most impossible of conclusions.” ― George Santayana

“History is a pack of lies about events that never happened told by people who weren’t there. . . . History is always written wrong, and so always needs to be rewritten.” ― George Santayana

“Scepticism is the chastity of the intellect, and it is shameful to surrender it too soon or to the first comer: there is nobility in preserving it coolly and proudly through long youth, until at last, in the ripeness of instinct and discretion, it can be safely exchanged for fidelity and happiness.”

― George Santayana

“The best men in all ages keep classic traditions alive.”

― George Santayana

A lot on Rhodes in here, hat tip mark.

Yes. An excellent read. It gets more into he was all in on the New World Order, and he was a raging Homo who surrounded himself with lads in his dying days.

Yes, he was a homo and had a live-in lover whom he left a good piece of his estate to.

He also borrowed money from Rothschild’s to get started. What I had read long ago when

legacy was more truthful was his father sent him to Africa d/t his being a homo. Disgrace.

So much drama, intrigue, and skullduggery. I don’t think I will ever understand what drives some men (and women) to spend their entire lives trying to dominate and control entire countries and even entire continents. Normal people are happy just living a simple life with family, friends, and some enjoyable hobbies, without trying to control everyone else on the planet. He might have lived to be older than 48 if his life had been simpler.

People crave trust in others because Godot is nowhere to be found, never shows, & plurals don’t trust themselves.

Quants take illusory Ease in printing words, (these words is)money, Ox Bow nooses, sitting in the docks of their piers, etc. Looks like nuthin’s gonna change … 🎶 ~ Otis Redding

Those who don’t know pathology are path dependent … but so are plenty who do know pathology, like it a lot, & take the path superhighway’d by. “When in Rome,” those say

Sexual appetites of many male homos would be accurately referred to as addiction, nympho-satyriasis, among heteros. And that pathology does not compartmentalize neatly to sex alone.

Insatiable, never enough, suffuses the moremoremor/organisms. Black holes, all around.

(Been reading about “mitochondrial uncoupling” … billionaires & buggerers power plants seem better-spelled/escribed mitocon’dria. Takes a tach to count those couple-uncouple revs. & takes a lot of lube workers/followers to cool those engines, too.)

I’ve heard Rhodesian Ridgebacks are good dogs, but waiting on Godogs is no wait at all – those are everywhere.

Good people? Goooood Morning, Vietnaaaam!

The ghost of Dean Moriarty types among us.

Interesting. Gore Vidal, one of the prolifics I thought about, wrote about having his way with Kerouac. He also wrote that there was never, ever, a shortage of willing partners – even when everybody was in WW2 uniforms.

(he didn’t go into billionaire’ing & quit politics early {was quit by it, more accurately} … putting some large portion of that appetite, I suppose, into writing. i’ve said before that bulldog Buckley lost & would have lost again had the encounter escalated.)

Insatiable appetite – by their fruits you will conservatively assume these strange fruits are known – in an intelligent species, would be an exclusionary bar to the country clubs that billionaires & bathhouse boys & child molesters have their ways with.

But “intelligence” people have uses for those people.

As do unintelligent people.

Brilliant IF – thank you. I trained for Nam in 1963 but never went – the angels always guarded me all my life: Psalm 91 – check it out:

Yep – we gotta get out of this place – and soon baby!