Guest Post by Hardscrabble Farmer

It’s easy to dismiss people who have no scientific credentials when they question scientific discoveries. The reasoning is that because they are untrained and have no formal training their input is not relevant if it counters established policy or position. To some degree this is a valid point, but we must also recall that men like Tesla, Copernicus and Edison were not degree holding scientists and their contributions to the field are beyond compare. Science is about observation, testable explanations and predictions about the mechanics of the physical world.

Anyone can perform a simple experiment, we teach the discipline to children, we use our knowledge daily in the act of living our lives, from boiling water to cleaning our homes. Many experiments require complex equipment, costly environments and extensive knowledge of mathematics and physics, and so people delegate these outcomes to those with access, trusting them to be truthful and without guile about the results. Often, due to the costs associated, scientists must rely on funding from government, academic institutions and corporate sponsors. Often there are strings attached and certain results desired.

It is a rare person who can stand up to both authority and the man who controls the financial strings that come with these arrangements. A former neighbor of mine was the CEO of one of the largest polling organizations in the country. Most people believe that polling is based on scientific sampling of populations in order to better understand opinions with narrow margins of error. During one particular discussion I asked him how he was able to determine with certainty what a given opinion was and he said, “That’s easy, it’s whatever the guy who writes the check wants it to be.”

The greatest single lesson I ever learned from my Father, the best teacher I ever had, was to question authority. He was the one who taught me about men like Stanley Milgram and Tomas de Torquemada and the lessons of blind acquiescence to men in positions of authority. I didn’t always listen to him and some of my only regrets in life are tied to my failure to remember what he taught me.

As I become older and the bonds of social acceptance and approval become increasingly meaningless, I have begun to look into things that stir my curiosity, to test for myself long held beliefs based on the observations and conclusions of others, to see if I can replicate the same solutions to my satisfaction. I understand that there are some things that I will never know and I guess I can live with that, but nothing will ever keep me from following that thread that leads me to some kind of understanding of the mechanics of the world. It is far too beautiful to allow someone else to experience that for me.

Open Science Collaboration is a group that tests scientific research under the same criteria as the peer reviewed papers that have already been published, in numerous disciplines. As the article below shows, the majority of those tested fail to reach the original conclusions, even when the original scientists collaborate under the same conditions. Peer review used to mean peer duplicated. Today over 90% of all peer reviewed work is not duplicated, merely proofread by fellow scientists.

That is a problem and it leads to doubt, justifiably. As I have posted in other threads in the past I no longer trust the official narrative of numerous disciplines, not because they are necessarily false, but because the authority that stands behind the claims has proven itself to be unreliable and no longer worthy of trust. As much as I am saddened by no longer accepting the uplifting stories of mankind’s greatest accomplishments, it is far more depressing to think that the reason behind it is the duplicity and deception of the very authority that may have made those successes a possibility.

Scientific Regress by William A. Wilson

The problem with science is that so much of it simply isn’t. Last summer, the Open Science Collaboration announced that it had tried to replicate one hundred published psychology experiments sampled from three of the most prestigious journals in the field. Scientific claims rest on the idea that experiments repeated under nearly identical conditions ought to yield approximately the same results, but until very recently, very few had bothered to check in a systematic way whether this was actually the case. The OSC was the biggest attempt yet to check a field’s results, and the most shocking. In many cases, they had used original experimental materials, and sometimes even performed the experiments under the guidance of the original researchers. Of the studies that had originally reported positive results, an astonishing 65 percent failed to show statistical significance on replication, and many of the remainder showed greatly reduced effect sizes.

Their findings made the news, and quickly became a club with which to bash the social sciences. But the problem isn’t just with psychology. There’s an unspoken rule in the pharmaceutical industry that half of all academic biomedical research will ultimately prove false, and in 2011 a group of researchers at Bayer decided to test it. Looking at sixty-seven recent drug discovery projects based on preclinical cancer biology research, they found that in more than 75 percent of cases the published data did not match up with their in-house attempts to replicate. These were not studies published in fly-by-night oncology journals, but blockbuster research featured in Science, Nature, Cell, and the like. The Bayer researchers were drowning in bad studies, and it was to this, in part, that they attributed the mysteriously declining yields of drug pipelines. Perhaps so many of these new drugs fail to have an effect because the basic research on which their development was based isn’t valid.

When a study fails to replicate, there are two possible interpretations. The first is that, unbeknownst to the investigators, there was a real difference in experimental setup between the original investigation and the failed replication. These are colloquially referred to as “wallpaper effects,” the joke being that the experiment was affected by the color of the wallpaper in the room. This is the happiest possible explanation for failure to reproduce: It means that both experiments have revealed facts about the universe, and we now have the opportunity to learn what the difference was between them and to incorporate a new and subtler distinction into our theories.

The other interpretation is that the original finding was false. Unfortunately, an ingenious statistical argument shows that this second interpretation is far more likely. First articulated by John Ioannidis, a professor at Stanford University’s School of Medicine, this argument proceeds by a simple application of Bayesian statistics. Suppose that there are a hundred and one stones in a certain field. One of them has a diamond inside it, and, luckily, you have a diamond-detecting device that advertises 99 percent accuracy. After an hour or so of moving the device around, examining each stone in turn, suddenly alarms flash and sirens wail while the device is pointed at a promising-looking stone. What is the probability that the stone contains a diamond?

Most would say that if the device advertises 99 percent accuracy, then there is a 99 percent chance that the device is correctly discerning a diamond, and a 1 percent chance that it has given a false positive reading. But consider: Of the one hundred and one stones in the field, only one is truly a diamond. Granted, our machine has a very high probability of correctly declaring it to be a diamond. But there are many more diamond-free stones, and while the machine only has a 1 percent chance of falsely declaring each of them to be a diamond, there are a hundred of them. So if we were to wave the detector over every stone in the field, it would, on average, sound twice—once for the real diamond, and once when a false reading was triggered by a stone. If we know only that the alarm has sounded, these two possibilities are roughly equally probable, giving us an approximately 50 percent chance that the stone really contains a diamond.

This is a simplified version of the argument that Ioannidis applies to the process of science itself. The stones in the field are the set of all possible testable hypotheses, the diamond is a hypothesized connection or effect that happens to be true, and the diamond-detecting device is the scientific method. A tremendous amount depends on the proportion of possible hypotheses which turn out to be true, and on the accuracy with which an experiment can discern truth from falsehood. Ioannidis shows that for a wide variety of scientific settings and fields, the values of these two parameters are not at all favorable.

For instance, consider a team of molecular biologists investigating whether a mutation in one of the countless thousands of human genes is linked to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s. The probability of a randomly selected mutation in a randomly selected gene having precisely that effect is quite low, so just as with the stones in the field, a positive finding is more likely than not to be spurious—unless the experiment is unbelievably successful at sorting the wheat from the chaff. Indeed, Ioannidis finds that in many cases, approaching even 50 percent true positives requires unimaginable accuracy. Hence the eye-catching title of his paper: “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.”

What about accuracy? Here, too, the news is not good. First, it is a de facto standard in many fields to use one in twenty as an acceptable cutoff for the rate of false positives. To the naive ear, that may sound promising: Surely it means that just 5 percent of scientific studies report a false positive? But this is precisely the same mistake as thinking that a stone has a 99 percent chance of containing a diamond just because the detector has sounded. What it really means is that for each of the countless false hypotheses that are contemplated by researchers, we accept a 5 percent chance that it will be falsely counted as true—a decision with a considerably more deleterious effect on the proportion of correct studies.

Paradoxically, the situation is actually made worse by the fact that a promising connection is often studied by several independent teams. To see why, suppose that three groups of researchers are studying a phenomenon, and when all the data are analyzed, one group announces that it has discovered a connection, but the other two find nothing of note. Assuming that all the tests involved have a high statistical power, the lone positive finding is almost certainly the spurious one. However, when it comes time to report these findings, what happens? The teams that found a negative result may not even bother to write up their non-discovery. After all, a report that a fanciful connection probably isn’t true is not the stuff of which scientific prizes, grant money, and tenure decisions are made.

And even if they did write it up, it probably wouldn’t be accepted for publication. Journals are in competition with one another for attention and “impact factor,” and are always more eager to report a new, exciting finding than a killjoy failure to find an association. In fact, both of these effects can be quantified. Since the majority of all investigated hypotheses are false, if positive and negative evidence were written up and accepted for publication in equal proportions, then the majority of articles in scientific journals should report no findings. When tallies are actually made, though, the precise opposite turns out to be true: Nearly every published scientific article reports the presence of an association. There must be massive bias at work.

Ioannidis’s argument would be potent even if all scientists were angels motivated by the best of intentions, but when the human element is considered, the picture becomes truly dismal. Scientists have long been aware of something euphemistically called the “experimenter effect”: the curious fact that when a phenomenon is investigated by a researcher who happens to believe in the phenomenon, it is far more likely to be detected. Much of the effect can likely be explained by researchers unconsciously giving hints or suggestions to their human or animal subjects, perhaps in something as subtle as body language or tone of voice. Even those with the best of intentions have been caught fudging measurements, or making small errors in rounding or in statistical analysis that happen to give a more favorable result. Very often, this is just the result of an honest statistical error that leads to a desirable outcome, and therefore it isn’t checked as deliberately as it might have been had it pointed in the opposite direction.

But, and there is no putting it nicely, deliberate fraud is far more widespread than the scientific establishment is generally willing to admit. One way we know that there’s a great deal of fraud occurring is that if you phrase your question the right way, scientists will confess to it. In a survey of two thousand research psychologists conducted in 2011, over half of those surveyed admitted outright to selectively reporting those experiments which gave the result they were after. Then the investigators asked respondents anonymously to estimate how many of their fellow scientists had engaged in fraudulent behavior, and promised them that the more accurate their guesses, the larger a contribution would be made to the charity of their choice. Through several rounds of anonymous guessing, refined using the number of scientists who would admit their own fraud and other indirect measurements, the investigators concluded that around 10 percent of research psychologists have engaged in outright falsification of data, and more than half have engaged in less brazen but still fraudulent behavior such as reporting that a result was statistically significant when it was not, or deciding between two different data analysis techniques after looking at the results of each and choosing the more favorable.

Many forms of statistical falsification are devilishly difficult to catch, or close enough to a genuine judgment call to provide plausible deniability. Data analysis is very much an art, and one that affords even its most scrupulous practitioners a wide degree of latitude. Which of these two statistical tests, both applicable to this situation, should be used? Should a subpopulation of the research sample with some common criterion be picked out and reanalyzed as if it were the totality? Which of the hundreds of coincident factors measured should be controlled for, and how? The same freedom that empowers a statistician to pick a true signal out of the noise also enables a dishonest scientist to manufacture nearly any result he or she wishes. Cajoling statistical significance where in reality there is none, a practice commonly known as “p-hacking,” is particularly easy to accomplish and difficult to detect on a case-by-case basis. And since the vast majority of studies still do not report their raw data along with their findings, there is often nothing to re-analyze and check even if there were volunteers with the time and inclination to do so.

One creative attempt to estimate how widespread such dishonesty really is involves comparisons between fields of varying “hardness.” The author, Daniele Fanelli, theorized that the farther from physics one gets, the more freedom creeps into one’s experimental methodology, and the fewer constraints there are on a scientist’s conscious and unconscious biases. If all scientists were constantly attempting to influence the results of their analyses, but had more opportunities to do so the “softer” the science, then we might expect that the social sciences have more papers that confirm a sought-after hypothesis than do the physical sciences, with medicine and biology somewhere in the middle. This is exactly what the study discovered: A paper in psychology or psychiatry is about five times as likely to report a positive result as one in astrophysics. This is not necessarily evidence that psychologists are all consciously or unconsciously manipulating their data—it could also be evidence of massive publication bias—but either way, the result is disturbing.

Speaking of physics, how do things go with this hardest of all hard sciences? Better than elsewhere, it would appear, and it’s unsurprising that those who claim all is well in the world of science reach so reliably and so insistently for examples from physics, preferably of the most theoretical sort. Folk histories of physics combine borrowed mathematical luster and Whiggish triumphalism in a way that journalists seem powerless to resist. The outcomes of physics experiments and astronomical observations seem so matter-of-fact, so concretely and immediately connected to underlying reality, that they might let us gingerly sidestep all of these issues concerning motivated or sloppy analysis and interpretation. “E pur si muove,” Galileo is said to have remarked, and one can almost hear in his sigh the hopes of a hundred science journalists for whom it would be all too convenient if Nature were always willing to tell us whose theory is more correct.

And yet the flight to physics rather gives the game away, since measured any way you like—volume of papers, number of working researchers, total amount of funding—deductive, theory-building physics in the mold of Newton and Lagrange, Maxwell and Einstein, is a tiny fraction of modern science as a whole. In fact, it also makes up a tiny fraction of modern physics. Far more common is the delicate and subtle art of scouring inconceivably vast volumes of noise with advanced software and mathematical tools in search of the faintest signal of some hypothesized but never before observed phenomenon, whether an astrophysical event or the decay of a subatomic particle. This sort of work is difficult and beautiful in its own way, but it is not at all self-evident in the manner of a falling apple or an elliptical planetary orbit, and it is very sensitive to the same sorts of accidental contamination, deliberate fraud, and unconscious bias as the medical and social-scientific studies we have discussed. Two of the most vaunted physics results of the past few years—the announced discovery of both cosmic inflation and gravitational waves at the BICEP2 experiment in Antarctica, and the supposed discovery of superluminal neutrinos at the Swiss-Italian border—have now been retracted, with far less fanfare than when they were first published.

Many defenders of the scientific establishment will admit to this problem, then offer hymns to the self-correcting nature of the scientific method. Yes, the path is rocky, they say, but peer review, competition between researchers, and the comforting fact that there is an objective reality out there whose test every theory must withstand or fail, all conspire to mean that sloppiness, bad luck, and even fraud are exposed and swept away by the advances of the field.

So the dogma goes. But these claims are rarely treated like hypotheses to be tested. Partisans of the new scientism are fond of recounting the “Sokal hoax”—physicist Alan Sokal submitted a paper heavy on jargon but full of false and meaningless statements to the postmodern cultural studies journal Social Text, which accepted and published it without quibble—but are unlikely to mention a similar experiment conducted on reviewers of the prestigious British Medical Journal. The experimenters deliberately modified a paper to include eight different major errors in study design, methodology, data analysis, and interpretation of results, and not a single one of the 221 reviewers who participated caught all of the errors. On average, they caught fewer than two—and, unbelievably, these results held up even in the subset of reviewers who had been specifically warned that they were participating in a study and that there might be something a little odd in the paper that they were reviewing. In all, only 30 percent of reviewers recommended that the intentionally flawed paper be rejected.

If peer review is good at anything, it appears to be keeping unpopular ideas from being published. Consider the finding of another (yes, another) of these replicability studies, this time from a group of cancer researchers. In addition to reaching the now unsurprising conclusion that only a dismal 11 percent of the preclinical cancer research they examined could be validated after the fact, the authors identified another horrifying pattern: The “bad” papers that failed to replicate were, on average, cited far more often than the papers that did! As the authors put it, “some non-reproducible preclinical papers had spawned an entire field, with hundreds of secondary publications that expanded on elements of the original observation, but did not actually seek to confirm or falsify its fundamental basis.”

What they do not mention is that once an entire field has been created—with careers, funding, appointments, and prestige all premised upon an experimental result which was utterly false due either to fraud or to plain bad luck—pointing this fact out is not likely to be very popular. Peer review switches from merely useless to actively harmful. It may be ineffective at keeping papers with analytic or methodological flaws from being published, but it can be deadly effective at suppressing criticism of a dominant research paradigm. Even if a critic is able to get his work published, pointing out that the house you’ve built together is situated over a chasm will not endear him to his colleagues or, more importantly, to his mentors and patrons.

Older scientists contribute to the propagation of scientific fields in ways that go beyond educating and mentoring a new generation. In many fields, it’s common for an established and respected researcher to serve as “senior author” on a bright young star’s first few publications, lending his prestige and credibility to the result, and signaling to reviewers that he stands behind it. In the natural sciences and medicine, senior scientists are frequently the controllers of laboratory resources—which these days include not just scientific instruments, but dedicated staffs of grant proposal writers and regulatory compliance experts—without which a young scientist has no hope of accomplishing significant research. Older scientists control access to scientific prestige by serving on the editorial boards of major journals and on university tenure-review committees. Finally, the government bodies that award the vast majority of scientific funding are either staffed or advised by distinguished practitioners in the field.

All of which makes it rather more bothersome that older scientists are the most likely to be invested in the regnant research paradigm, whatever it is, even if it’s based on an old experiment that has never successfully been replicated. The quantum physicist Max Planck famously quipped: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” Planck may have been too optimistic. A recent paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research studied what happens to scientific subfields when star researchers die suddenly and at the peak of their abilities, and finds that while there is considerable evidence that young researchers are reluctant to challenge scientific superstars, a sudden and unexpected death does not significantly improve the situation, particularly when “key collaborators of the star are in a position to channel resources (such as editorial goodwill or funding) to insiders.”

In the idealized Popperian view of scientific progress, new theories are proposed to explain new evidence that contradicts the predictions of old theories. The heretical philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend, on the other hand, claimed that new theories frequently contradict the best available evidence—at least at first. Often, the old observations were inaccurate or irrelevant, and it was the invention of a new theory that stimulated experimentalists to go hunting for new observational techniques to test it. But the success of this “unofficial” process depends on a blithe disregard for evidence while the vulnerable young theory weathers an initial storm of skepticism. Yet if Feyerabend is correct, and an unpopular new theory can ignore or reject experimental data long enough to get its footing, how much longer can an old and creaky theory, buttressed by the reputations and influence and political power of hundreds of established practitioners, continue to hang in the air even when the results upon which it is premised are exposed as false?

The hagiographies of science are full of paeans to the self-correcting, self-healing nature of the enterprise. But if raw results are so often false, the filtering mechanisms so ineffective, and the self-correcting mechanisms so compromised and slow, then science’s approach to truth may not even be monotonic. That is, past theories, now “refuted” by evidence and replaced with new approaches, may be closer to the truth than what we think now. Such regress has happened before: In the nineteenth century, the (correct) vitamin C deficiency theory of scurvy was replaced by the false belief that scurvy was caused by proximity to spoiled foods. Many ancient astronomers believed the heliocentric model of the solar system before it was supplanted by the geocentric theory of Ptolemy. The Whiggish view of scientific history is so dominant today that this possibility is spoken of only in hushed whispers, but ours is a world in which things once known can be lost and buried.

And even if self-correction does occur and theories move strictly along a lifecycle from less to more accurate, what if the unremitting flood of new, mostly false, results pours in faster? Too fast for the sclerotic, compromised truth-discerning mechanisms of science to operate? The result could be a growing body of true theories completely overwhelmed by an ever-larger thicket of baseless theories, such that the proportion of true scientific beliefs shrinks even while the absolute number of them continues to rise. Borges’s Library of Babel contained every true book that could ever be written, but it was useless because it also contained every false book, and both true and false were lost within an ocean of nonsense.

Which brings us to the odd moment in which we live. At the same time as an ever more bloated scientific bureaucracy churns out masses of research results, the majority of which are likely outright false, scientists themselves are lauded as heroes and science is upheld as the only legitimate basis for policy-making. There’s reason to believe that these phenomena are linked. When a formerly ascetic discipline suddenly attains a measure of influence, it is bound to be flooded by opportunists and charlatans, whether it’s the National Academy of Science or the monastery of Cluny.

This comparison is not as outrageous as it seems: Like monasticism, science is an enterprise with a superhuman aim whose achievement is forever beyond the capacities of the flawed humans who aspire toward it. The best scientists know that they must practice a sort of mortification of the ego and cultivate a dispassion that allows them to report their findings, even when those findings might mean the dashing of hopes, the drying up of financial resources, and the loss of professional prestige. It should be no surprise that even after outgrowing the monasteries, the practice of science has attracted souls driven to seek the truth regardless of personal cost and despite, for most of its history, a distinct lack of financial or status reward. Now, however, science and especially science bureaucracy is a career, and one amenable to social climbing. Careers attract careerists, in Feyerabend’s words: “devoid of ideas, full of fear, intent on producing some paltry result so that they can add to the flood of inane papers that now constitutes ‘scientific progress’ in many areas.”

If science was unprepared for the influx of careerists, it was even less prepared for the blossoming of the Cult of Science. The Cult is related to the phenomenon described as “scientism”; both have a tendency to treat the body of scientific knowledge as a holy book or an a-religious revelation that offers simple and decisive resolutions to deep questions. But it adds to this a pinch of glib frivolity and a dash of unembarrassed ignorance. Its rhetorical tics include a forced enthusiasm (a search on Twitter for the hashtag “#sciencedancing” speaks volumes) and a penchant for profanity. Here in Silicon Valley, one can scarcely go a day without seeing a t-shirt reading “Science: It works, b—es!” The hero of the recent popular movie The Martian boasts that he will “science the sh— out of” a situation. One of the largest groups on Facebook is titled “I f—ing love Science!” (a name which, combined with the group’s penchant for posting scarcely any actual scientific material but a lot of pictures of natural phenomena, has prompted more than one actual scientist of my acquaintance to mutter under her breath, “What you truly love is pictures”). Some of the Cult’s leaders like to play dress-up as scientists—Bill Nye and Neil deGrasse Tyson are two particularly prominent examples— but hardly any of them have contributed any research results of note. Rather, Cult leadership trends heavily in the direction of educators, popularizers, and journalists.

At its best, science is a human enterprise with a superhuman aim: the discovery of regularities in the order of nature, and the discerning of the consequences of those regularities. We’ve seen example after example of how the human element of this enterprise harms and damages its progress, through incompetence, fraud, selfishness, prejudice, or the simple combination of an honest oversight or slip with plain bad luck. These failings need not hobble the scientific enterprise broadly conceived, but only if scientists are hyper-aware of and endlessly vigilant about the errors of their colleagues . . . and of themselves. When cultural trends attempt to render science a sort of religion-less clericalism, scientists are apt to forget that they are made of the same crooked timber as the rest of humanity and will necessarily imperil the work that they do. The greatest friends of the Cult of Science are the worst enemies of science’s actual practice.

William A. Wilson is a software engineer in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Oh, boy …… this has shit-fest written all over it. Should I stay, or should I go?

Seriously, no SF intended. If you can’t talk about things like this here, where are you supposed to go?

Again, I don’t “believe” in flat earth/no Moon/whatever, I just don’t accept the official narrative. They burned that bridge on their own, not me. You don’t want people believing crazy things, don’t put an all seeing eye on the top of a pyramid on the back of a dollar bill. That’s just asking for trouble.

[img [/img]

[/img]

“At its best, science is a human enterprise with a superhuman aim: the discovery of regularities in the order of nature, and the discerning of the consequences of those regularities.”

====

How is that supposed to be “superhuman”? The scientific method is chiefly an error-checking system created and followed in order to make reliably effective inquiry into aspects of the phenomenal universe.

Hell, that’s the most thoroughly “human” kind of activity there is. After all, we’re the only species thus far shown to be capable of it.

Stay Stucky!

You can take this one on.

I can’t do this anymore. There is no point.

A nice person at NASA got back to me with scientific explanations of what was going on in that montage posted last week. Quite reasoned and logical. I am not going to bother posting. Like I said there is no point. It’s always a God of the Gaps paradigm I am faced with. But this and but that.

The titles Question Authority and What’s wrong with this Picture are dishonest titles from the get go! In my opinion. HSF if this is how you frame your life then that’s fine. But you seem to be setting up this paradigm which I can turn back easily on you as well.

Now these aren’t your words but you did post them

“science is a human enterprise with a superhuman aim”

I could say the same thing about religion and nobody can prove me wrong. So what is the point. I will read it more thoroughly tonight. I could be off base but in my initial observation of this article it ends with a conclusion that is non sequitor.

I guess if we follow this logic we should not believe in anything. Seems a scary way to go through life but it’s a life that’s yours. Live and let live. A Libertarian view that I hold.

Oh yeah. The good Doctor said that he would take me on a tour of the Goddard Space Center if I can make it down that way.

Should I go?

Today I have decided to be a dumb ass. But I am going to be nice. Now you and Araven might not believe this but I respect your close held skepticism of science. I just think it’s misplaced. Now I did dopple myself last week in debate with Araven and Cz and yourself. Why? Well because being a dickhead comes naturally for me. Just ask my boss. But I did it to draw out what the underlying problem was with Araven’s position. HSF I still don’t know what is the underlying problem is with you. Even after a cursory reading of this piece.

Last week I asked you to go outside and look at sedimentary sequences of rocks present no doubt in your corner of world. I’m using corner so as to not show what you obviously think is my bias. I could be wrong but it looks to me like you didn’t do this.

Anyways this debate while metaphysical in scope is pointless in practice. At least for me. I can’t change your close held beliefs even though I don’t know what they are. I have often wondered why I didn’t become an academic. More than likely because people sat around and did much ado about nothing. Maybe I should have applied myself more in university. Become a real scientist. Whatever that is. Placed “Dr. or Engineer ” in front of my name. Joined the priest class as you infer.

But I didn’t I just grew old and now sit at a desk sipping coffee and detailing rebar.

and typing on the internet.

🙂

Rob I simply do not understand the response. If I gave any indication that I found you personally to be unreliable or false you are mistaken and I apologize for being inarticulate. Beyond that there isn’t anything I can add.

If someone sent you a proof, why wouldn’t you post it? What are you trying to do teach us a lesson? Like the article implies, being able to prove the science through testing is the way you get to a conclusion that EVERYONE can accept, not coming to conclusions based on who pays for the study.

On Friday I’m taking my 8 year old to a 24 hours in space program at the planetarium, followed by a night of sky watching/star gazing. I’d love to be able to prove some of these things through simple mathematics and observation, it can’t possibly be that far above anyone’s head because at some point it was ALL amateurs trying to figure things out. It’s the bad data, deliberately falsified images, etc. that lead to doubt, not overly complex science. I’m not sure why you are having such a difficult time with that and making it personal when it clearly has nothing to do with you or me.

I agree with a lot of what this post presents. My experience has been that the God’s of the Copybook do not want, nor do they need, your thoughts on any subject in which they have become an expert. It doesn’t matter what your interest might be in the subject and it doesn’t matter what subject it might be. The “experts” vigorously defend their academic hilltop. As they should. It is their income stream and just as your income stream is important to you, theirs is important to them. Fair enough.

What I find to be most annoying is that the scientific method system has been used to build walls around knowledge so as to monetize it. There is actually a direct conflict between capitalism and the scientific method.

“For neither can live while the other survives.”

“You don’t want people believing crazy things, don’t put an all seeing eye on the top of a pyramid on the back of a dollar bill. That’s just asking for trouble.”

Lol. Comment of the day….

Oh and my corner of the world is granite ledge, I’d have to shoot over to Vermont to find sedimentary.

FWIW I lived in Hopewell most of my life which was made up of Brunswick shale/Ordovician deposits and Argillite. I’m not a Creationist, I understand epochs and eras and I’m not some kind of geology denier.

And there is no “underlying problem with me”, I just swing back and forth between jaw dropping awe at the world I live in and pitch- black cynicism at the way human beings deliberately manipulate other human beings in order to exercise power over them. Nature doesn’t hide anything, humans obfuscate everything.

So, peace and all that jazz.

@HSF

It was a joy to read the English language used to explain the present

state and status of scientific research. “Scientific Regress,” by William

A. Wilson. (no wasted words)

I read this carefully and slowly, and reread. My minor experience, in college,

learning mostly about the scientific method, allowed me to actively visualize

the environment and the process. Lucky for me, there were adequate and patient

instructors.

All said and done…in lament or just understanding the rudiments…HSF’s neighbor

had the business down.

“During one particular discussion I asked him how he was able to determine with certainty what a given opinion was and he said, “That’s easy, it’s whatever the guy who writes the check wants it to be.”

So solly, so sad,

Suzanna

The title should have say question everything. I won’t post because what’s the point. You are not going to believe it. I don’t know why but you won’t. At least based on what you wrote in original post.

Right now it’s raining outside my window. I can see that it’s raining but I can’t touch it. Am I lying in telling you that it is raining in Antigonish Nova Scotia. If I went outside and got wet. Came back in and told you so. Would you believe me then. Where does it end. Would I have to send a Lear Jet to your state transport you back here so that I could make you believe. If I did would then tell me that while it’s raining now you can’t prove to me that it was raining when I typed this post.

Okay fine go to planetarium. Believe in bad data and falsified images. I can’t help you. I just think it is a bad way to proceed thru life.

HSF….regardless of prior citations on your admirable writing skills, the intro you wrote to this post was your best work Evah!!!

It is about time the real skinny on ‘science’ of all types was examined, and it was accomplished magnificently.

We know that humans kill with impunity, cheat/steal from same; governments treat their citizens a tax slaves and punish those that dare to deter from the political position of authority – scientists are human animals – do not expect them to differ from the bell curve of the population as a whole.

Note to self: Stay out of science threads. Folks get wound way too tight over them. Oh, by the way, does anyone know if we really landed on the moon?

CO2 good advice. I’m out.

Stucky can take this one.

“I won’t post because what’s the point. You are not going to believe it. I don’t know why but you won’t…”

There’s the hitch, Rob. I don’t want to believe what someone else has told me is true, I want to believe it because I know it to be. If he has proven it to his satisfaction, then he must be able to articulate the methods, data and theorems that led to that knowledge and I must be able to follow them to the same conclusion. I am not a mathematician, but I can teach the Fibonacci sequence to a six year old and have them not only grasp it, but go on to explain it to others without there being any loss of understanding in the translation. It is repeatable, it is unerring and it is as beautiful as any sunset because it demonstrates an ineffable truth about the world in which we live.

@Rob in Nova Scotia

You seem upset by the choice of one or 2 words and their

meaning. Those don’t matter really. (just nuance, mole hills)

The issue at hand is that present “scientific research” is bought

and paid for to further an agenda. That is what we need to understand.

We can not trust the science.

See Loretta Lynch above. Don’t like the science? You had better keep

it to yourself. It is the Mafia at work, not “science.”

HSF

Thanks for the article. I have become more skeptical as I grow older (was pretty skeptical when younger!). Remember well the myriad scientific studies about coffee being bad, then good, then bad, etc. Same for eggs, global warming vs global cooling (a few decades ago, it was proposed that carbon soot be spread on the poles to counter the horrible upcoming global freezing), statins, and so on. Never mind the ” softer sciences” as economics or social studies that predict human behavior.

It is not the methodology of a proper scientific study, but the biases that many times counteract the results that invalidate many findings.

Admin, I have a couple of papers that fit well with HSF’s exploration for scientific truth. I’d like you to consider them for posting on TBP. I’m a long time lurker, first time commenter. I think my paper’s will continue the shitfest. You can view the first one here:

. Can you e-mail me? Thanks. Dan.

Suzanna

I’m not upset. Maybe sad or tired. Not sure.

Suzanna

An extraordinary claim 100% of science is bought and paid for. Really. Evidence much?

ILuvCO2: Moon Landing: Fake! Level of certainty: 100%

Rob IN: Follow the money. http://www.powerlineblog.com/archives/2015/08/global-warming-a-1-5-trillion-industry.php Make that 100% of Climate Science; NASA, NOAA; EPA, the list goes on; don’t know about the rest.

Rob writes: “What I find to be most annoying is that the scientific method system has been used to build walls around knowledge so as to monetize it. There is actually a direct conflict between capitalism and the scientific method.”

==============

Precisely the reverse. What scientific method effects is an opening of the processes of observation, analysis, and interpretation to anyone and everyone who cares to examine what’s presented.

It doesn’t “build walls;” in fact, it obliges placement of the argument for any supported contention right to hellangone out in the open for all to see. Indeed, the hallmark of scientific method is independent reproducibility; those who read your methods and findings MUST be able to get the same results through emulation, else what you’ve presented is without validation.

Not only is there no “conflict between capitalism [the free market] and the scientific method” but it’s employment of the scientific method which helps to prove that a market economy free from coercive dirigisme is far superior in productivity as well as social comity than is any form of normative ordination by armed fuckwads in the guise of government.

“Oh, by the way, does anyone know if we really landed on the moon?”

Well, I know for sure that I didn’t land on the moon. Whuffo I wanna go to no damm moon fo’, huh? Whuffo?

The last place I would go for hard scientific evidence is to a source of the manufactured science.

That’s like asking a corrupt politician to send you proof he is not a crook.

One of the many things I have oft considered (but as is my wont, never actually started) is a piece on epistemology–the study of knowledge itself. I think most of us here consider ourselves to be seekers of Truth. But what exactly is that? Taking note of Schopenhauer’s observation that all debate is at its heart an exercise in semantics, I will first define my terms.

We don’t need to dig deeper than the wisdom of Obi-wan Kenobi to realize how slippery a slope the search for truth really is:

“You’re going to find that many of the truths we cling to depend greatly on our own point of view.”

This leads to the biggest question about truth and my definitions. (1) Truth (capital T) that which is true always, regardless of point of view, regardless of whether its even OBSERVED or not. (2) truth (small t) – That which is true always true from human perception.

The questions this leads to are these: (1) is there a difference between the two? and (2) could we possibly know if it there were?

As an illustration: During the time of the dinosaurs many of the scientific truths (they had biologies, musculature, circulatory, respiratory and nervious systems, there bodies were held to the ground by Gravity, their body chemistry’s governed by the same Fundamental Forces as ours, etc., etc.) but there were no sentient beings around to observe these truths. Capital T…or capital T Truth does not exist. Which I will come back to later.

Along these lines of though a couple of passages really stood out to me. One:

“an unpopular new theory can ignore or reject experimental data long enough to get its footing”

Really? I have no doubt that this is the way things really happen in the scientific community, but this is the pinnacle of hypocrisy. What does popularity have to do with truth? Or “footing” whatever that means? Does the Truth change based on whether it is widely accepted or rejected? That is Dogma powerful enough to make the Roman Catholic Church blush.

The other passage was quick and most readers would not register it:

“and the comforting fact that there is an objective reality…”

Is there? Of course, all science (all rational thought) is fundamentally based upon the idea that there is. This in and of itself creates a logical paradox loop. Science could accurately be defined as a mathematical description of a Rational Cosmos; BUT, every proof that the Cosmos IS rational, relies inherently on the Assumption that the Cosmos is Rational.

There is not one scientist in ten-thousand that would ever admit this paradox upon which their whole world view is based.

Stucky, the “Champion of the Official Story” asks if he should stay or go.

Oh do stay Stucky, so you can parrot the official line and call the rest of us fuktards. We like that.

should read: considered WRITING (but as is my wont, never actually started)

Excellent post HSF……….

As a former Search Manager, I can concur by saying the mathematical models and human interaction can also taint the desired results. Never take the so called “experts” assessments as gospel, nor dismiss the novice’s observations as trivial.

It leads to failure every time…………

The search for truth always runs up against the wall of Cognitive Dissonance: http://www.instructionaldesign.org/theories/cognitive-dissonance.html “According to cognitive dissonance theory, there is a tendency for individuals to seek consistency among their cognitions (i.e., beliefs, opinions). When there is an inconsistency between attitudes or behaviors (dissonance), something must change to eliminate the dissonance. In the case of a discrepancy between attitudes and behavior, it is most likely that the attitude will change to accommodate the behavior.

Two factors affect the strength of the dissonance: the number of dissonant beliefs, and the importance attached to each belief. There are three ways to eliminate dissonance: (1) reduce the importance of the dissonant beliefs, (2) add more consonant beliefs that outweigh the dissonant beliefs, or (3) change the dissonant beliefs so that they are no longer inconsistent.

Dissonance occurs most often in situations where an individual must choose between two incompatible beliefs or actions. The greatest dissonance is created when the two alternatives are equally attractive. Furthermore, attitude change is more likely in the direction of less incentive since this results in lower dissonance. In this respect, dissonance theory is contradictory to most behavioral theories which would predict greater attitude change with increased incentive (i.e., reinforcement).”

Good luck dislodging your existing belief system, especially if the belief contains an element of fearfulness. It takes the red pill.

Wait a minute, Bea. Are you tryna say that Stuck didn’t go to the moon?

Seems to me that HSF is strongly aligned with Karl Popper which, as a scientist by training, I take as a good thing.

I left the “scientific” world behind early in my career because it was even then (early 80’s) taking on the form of a popularity contest rather than true scientific endeavor. Training in critical thinking was being replaced with indoctrination. Cannot replicate the “Big Man’s” results? “Shut up about it already!”

The classical scientific method is a very simple four step process. (Look it up as I am not going to be pedantic it here.)

But there is a simple reality: If you cannot test an idea then you cannot “do science” with it. End of story.

If you CAN test an idea but the results are not consistently replicable then either your ability to formulate an idea or design a test method need work.

No scientific advance ever left a previously cherished “scientific fact” unravaged.

DaP

Ed…….Stucky was there on every moon landing because…….he believes….he believes…..he believes……….the official story(every time). It’s just easier to conform Ed, don’t you think?

On second thought, I’m going to save the taxpayers money, and defer prosecution of the website owner. Barrack’s relatives will hunt him down soon enough, due to that blasphemous display on Sunday, so I fully expect that issue to resolve itself shortly, at no expense to the taxpayer other than cleanup. Your public servant, Loretta Lynch

” It’s just easier to conform Ed, don’t you think?”

Well, I wannabe leave. I think it’s easier to corn farm than to truck drive, y’know?.

HSF, You many want to add this to your reading list. I just received my copy and it looks to be a revelation. Schauberger forsook a university education because he didn’t want to be corrupted by existing “knowledge”. He observed nature and the results are truly amazing:

Bea

I heard your sister wants to lick your nuts. Should I believe it?

HSF- There is one thing I am sure of, you can’t get ten pounds of sugar in a five pound bag.

I still want to know how they got that Lunar Rover in that tiny landing module as it was 3/4 the size of the module. I always carry a Honda Civic in the trunk of my Mercedes in case I need alternative transportation…………….Oh the science.

Don’t bother answering me HF, you never do.

Stucky just proved my point………..

I’m not a scientist, nor do I play one on teevee, but I’ve read that much of the “testing” performed for drug approval is bogus. I do think we went to the Moon more than once. According to some of the astronauts the aliens already there didn’t appreciate our visit, which is why we didn’t return after the Apollo program.

This thread reminds of an exchange I had with my Dad back when I was in grade school. We had been studying geology that day and I learned the great glaciers that flattened much of the Midwest had stopped around the Ohio River, which is why it’s hilly. When I told my Dad my newfound info, he looked at me, narrowed his eyes and said, “You don’t really believe that crap, do you”? He might have been onto something, either that or he just couldn’t wrap his head around something so utterly contrary to his belief system.

@Bea

Did you ever try a 2 second web search on the lunar rover? It folded up, and was unfolded as it deployed from the lander.

There’s a YT video showing them testing the deployment sequence. Check it out.

Thanks HSF, keep up the good work.

Check this out:

http://www.disclose.tv/action/viewvideo/224406/ron_howard_says_the_1969_apollo_11_ moon_landing_was_faked_in_a_studio/

Your Popeliness, that was some funny shit………….hahaha.

[img [/img]

[/img]

—————> Photoshop?

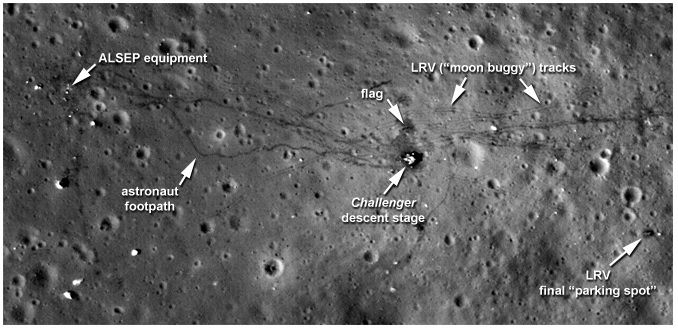

ALSEP euipment………hahaha

LRV final parking spot…………..hahaha.

Look…..there’s Stucky waving to us next to the LRV(moon buggy) tracks !!

Start believing Bea or this Man on The Moon will come to earth and smite you with my great sword!

Smite away MOTM, the IRS has already inflicted the fatal wound, you could do no more harm.

Well then

Avoid confusion in the coming Apocalypse. Change your name to IRS Bitch. Just to keep things believable! Man on moon so wiity……

[img &psig=AFQjCNE0JMX3hlLkHxj7P2qjzSumKSkhGg&ust=1460661091151549[/img]

&psig=AFQjCNE0JMX3hlLkHxj7P2qjzSumKSkhGg&ust=1460661091151549[/img]

I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.

Good piece, HSF, although I didn’t read all of the author’s part. I do agree with much of your reasoning on scientific method.

As to moon landings, this amateur astronomer’s webpage shows how to view the maned lunar landings:

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/observing/celestial-objects-to-watch/moon/how-to-see-all-six-apollo-moon-landing-sites/

But this comment has me baffled–how can the Hubble telescope see deep space objects but not discern artifacts left behind from the moon landings in detail? Maybe it’s a math issue/question…

“As you’re well aware, no telescope on Earth can see the leftover descent stages of the Apollo Lunar Modules or anything else Apollo-related. Not even the Hubble Space Telescope can discern evidence of the Apollo landings. The laws of optics define its limits.

Hubble’s 94.5-inch mirror has a resolution of 0.024″ in ultraviolet light, which translates to 141 feet (43 meters) at the Moon’s distance. In visible light, it’s 0.05″, or closer to 300 feet. Given that the largest piece of equipment left on the Moon after each mission was the 17.9-foot-high by 14-foot-wide Lunar Module, you can see the problem.”

There is a moon “conspiracy theory” that I do believe–it’s not a natural object. Too many anomalies relating to it’s size in relation to the Earth and Sun, physical characteristics, etc. Download and read Christopher Knight’s book “Who Built the Moon”. The latter chapters get into some questionable esoteric stuff, but he and the co-author point out many weird things about the moon that left my jaw hanging.

https://contraeducacao.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/who-built-the-moon_-knight-christopher.pdf

[img]data:image/jpeg;base64,/9j/4AAQSkZJRgABAQAAAQABAAD/2wBDABQODxIPDRQSEBIXFRQYHjIhHhwcHj0sLiQySUBMS0dARkVQWnNiUFVtVkVGZIhlbXd7gYKBTmCNl4x9lnN+gXz/2wBDARUXFx4aHjshITt8U0ZTfHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHx8fHz/wAARCAElAMEDASIAAhEBAxEB/8QAGwAAAgMBAQEAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAMBAgQFBgf/xAA6EAACAgECAQYNAwQDAQEAAAAAAQIDEQQhEhMVMUFRsQUiMjM0VGFjcXKSouEUI3MGJFKBQpGhNUP/xAAZAQACAwEAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAQIDBAX/xAAnEQACAgEEAgEEAwEAAAAAAAAAAQIRAwQSITFBURMUIjKBIzNhBf/aAAwDAQACEQMRAD8A5ut8I6yGu1EIXzUY2ySSk9lliOdNb6xZ9TI8If8A0NT/ACz72ZsGlJUUNs1c6a71iz6mHOmu9Ys+pmUMBSFbNXOmu9Ys+thzprvWLPqZkDAUh2zVzprvWLPrYc6a71iz62ZcBgVILZq5013rNn1MOddd6xZ9bMuCMCpDtmvnXXesWfUyOddd6xZ9TMoJN9CyFIOTVzrrvWbPrYc6671mz62ZuTn/AIMhxa6UwpByauddd6zZ9bDnXXes2fWzIGApBbNfOuu9Zs+tkc6671mz62ZSApBbNfOuu9Zs+thzrrvWbPrZkwTgKQWzXzrrvWbPrZHOuu9Zs+tmXABSFbNXOuu9Zs+thzrrvWbPrZlIwOkFs+igAGYvPEeEP/oan+WXezPg069f3+p/ll3sz4Na6Mz7K4DBbAYACuAwWwRgBkYDBeEJTkowTbfYd3wd/TzmlZqXhdhCUlHskot9HDp01t8kq4SefYdjS/03bNKV8lFPqTPR06enTQUaYKPtLcTfSZZZ2+jRHD7ObV/T+krxnik/aa6/B+kr25CL/wBGlSZDexS5yfktUEvAuWn0sVjkIf8ARnsp0j2dEP8Ao0T8ZGadcuwlG/YmkvAifgfRXp8K4X7DBqP6aW7ps/7Z1a4zUl1GlrJLfKPkWyMvB4rVeDdRpX48G12pGQ97PhmuCaUl7Tl67wHVcnKjxJdiLo5fZVLFXR5bAYNGp0lulm42RfxEYL1yUNUQGCcAMCCC2CAEfQwADKaDxWvX9/qf5Zd7EGjXr+/1P8su9iMGxdGZ9lcBgkMABGBmn089Raq61lsK6pWzUILLZ6zwXoIaGlSaza+llWSagi2EHJlvBfginRVqdiUre19RunanshNtj6Excc4yYncuWaopR6HOQt2pPBSVmEJdqUvGBRG5GyMsoJPtMUtZGLxEstVGe2Q2Me9GjlIx6yXfFR6sGC6yO+5kdjb6diahZBzOty6a2Qq2+a2RihdLGOobxcpHbpHtoTm2WhbLi3Zrps4nuzn4a6i9U5Jg0JSo2arTVaqtwsin7Ty3hHwZZo55W9b6GemVj6GWsrjfU67FlMcJOITipHiCDb4R0MtHc1jxH0MxmpO+TK1RAEgMR9BAAMpoPG6707Ufyy72IwaNcv77Ufyy72IwbV0Zn2VwBbA/Rad6jUxgl7RN0NcnY8A6BRh+psW78nJ15yLRUaqYwjskjLOzieI7mBtzlZtitkaJ4sy3Lp7MVjtJ40ukKFZS6cYdPSZJ25ZfVJt8SMjbLEiDZeT60VcivGWhHi36iVCKylvuVk1krZlSZCew6EOrks7vY6FajGC4d8nKjlvY01WSr2ZFoaZu5NS6Q5NJpoQ7m4+KKjqJReWQpkrRrnJ7YG1z4ks9Jlhap74waa2hNEkxfhDSx1WnlFrdLKPI2VuqyUJdMXg9vLZZPOeG9Pw2K2K2fSWYpeCvLHycgME4A0mc9+AAZDQeQ1vp2o/kl3iMGjWr+91H8ku8Qbl0ZX2Rg7ngCjEZXNb9RxMZeO09LoY8jooLraKc340W4vysffbjYRxqHxKTlxT36BNlqbKFEuchs9Rl7FJWN9ZmctyHYT2kbNDbfSxNkNsphxNrYmO0XlhQCFs9xmXHDzsLslhi3OTeMkqsVmvCmslOSWSKX2jnJJbEehhRWovcvZXmQtT3LqxvcQxigsbCpUvIct1ByuXuxAXr2jjsGxngS5JPJCsFQ7NqtysMx66HLaeS7Ny0Z7kSlnK7UCVMG7R5pxw2n1BgdqY8N817RRqRmZ7wAAyGg8lrV/e6j+SXeJwaNZ6bf/JLvEG9dGV9hBZsj8T0Tlw0QXYjgVedj8TsWz8RIqyK2izGwcljJksn4zGzlivYyyeWRSJtluIq3kjEuwjO/tGq8A012M48LBEZtspwyfUR0AqfQNNdk2SRMcYyUcZPqBcWOgVr2G2Xobx42LcZmec7l0pY6AaQ1bHqW3SV42KcmtgTbewqDnobxbkuW4vEuwhvAlT6G012jRx9G5HHuJUtiVINorNEZkue5njPBbiyLaOzDro4uz2mY1615mjKXR6KJdnugADIaDyus9Mv/kl3iDRrPTL/AOSXeJOgujK+yI7TT9pvnZmKMPWaOLxURkiUWN4vFESeJBxFZPIqJWbYvMUZYr97A+h5rKRj++zmQexzR2Mi+SOOQ8y2rFvxHuX7uPYLtj+7EjgeyXPlEtQlkhx4Y1+LAiveCK6h4qLU+bRU1/Hu/wBLU/5Nv+GXUP8AdZrr8hCrNPxy4s4HRjwxSLcuSMscUuyrDilHLKTXDMlicr8I0xhGuIqCzqG/YX1L4amOcnJxgRxxUFLIwjfCUsIm2tTjt0nPi8NM6cHmCHmx/A1KIsGX6hOM0YM42Di2C9cNrF5N8fuSZy5rbJoZxF1LIhMsmOiNi9S8zQrBezeTKk0itvk9uAAYjSeX1a/vL/5Jd4kfq/S7/wCSXeJwdFdGV9kYLxexXBK2HQIGQSQKh2aNK+lD+HxsmXTyxM18S7Tj6qLjkdeTuaOSliV+DM5f3CHuOZJmRv8Afz7TYpIM8XDa16FppKe5P2I1b2SG0+bRm1LzNI0VNKtDyRrDEMU1LUSE3XyhZhGiEuKCbMep3tZrra4F8AzY0sUWkLT5ZSzTTfAqDxqGvYX1K4qmZrZcN3EjVC2NkcdfYPJCUduRIWLJGanibOdFZkkdSKxBC1TXF8RW+9Ri1F7hlm9Q0ooMGNaWLlNmW+XFaxWSXu8kHSjHakjkTluk2GSckAOiNlXuwwTgMDEe0AAMBqPM6tf3d38ku8UO1Xpd38ku8UdJdIzPsqBIDEQCjxPCJLVecRGbqLZOC3SSZK0811kumztNMniLYuq3jk00ctajNJOSSpHWemwwkoNu2ZZQknh9IxU2YzxD70sJ+0uvIJT1UnBSSIQ0cVOUWzBJPiw+kYqbGtpEWecfxNkPILdRllCMWvJTpsEck5J+DEqpSk1ndEyqnCOeIfX56ROo82QeeXyKPgsWmh8cp+TOqJSSeRcouEsZ3N9Xm18DJf50lhzSnNxfRDPp4Y8amuyVVbJeUR+ln2jIajGFg09WSnJmy4nykXY8GHMuG2YXpZpdQnGGa56jdrBle7ya8LySX3mHURxRdYyuAwWwBeZiuAJwGBiPYgAHPNZ5vVelXfPLvFDtV6Vd88u8UdOPSMz7KhgkBiILV+WiC1floryfgyzF+aNTWVgpCEY5wWl5LE0uXE89BxccHKEmmd7JOMckU1bItlJyS6sj15BW1Lh3LR3ghzkpY40iOOLjllbuzJPy38TXDyTLOL5R7GqO0S/VtOEaM+jTU52Kr87Itf5BWve2Ra/yCEv7o/osj/RL9lq/IXwMt/nDVX5C+Bnui3PoJaZpZmQ1abwRoVHykb/+JiSakso2/wDElre4kP8AnqlKzBNeOypeflMrg6EfxRzJ/kyoFsBgZAqBOAGB64AA5xqPO6r0q755d4odqvSbvnfeJOnHpGZ9kASAxEEw2kmBApR3KiUXtaZp5SPaRykF1mcfpqFc2m8GB6LHFW2zf9fkfhC7bOLZdBNduFhmv9BH/IP0Ef8AIm4YXDZ4KVnyqe/yI449JWdyxhDv0UeU4cldRpI1VuSeSuGnxKSt2XS1mRqkqM9MlGTbL2zjKOEw01Kuk03gbqNJGqHEnktnig8u5vkphqJxx7K4KQsiopNk8rDtGV6KM61JvpLfoI/5FEtPibbtl0dbkSqkZbJxl0MZyscdJOo0kaa+JMyYLFpYTilfRFaycZN12RLeTZBOANiVKjE3bsgCQwMiRggsQAHrAADmmo89qfSbvnfeKHan0m3533izqR6RmfZUCcAMRUCQACC9dsqn4pUBNWM6GktlZFuQau2VSTiymg8lhr/JRlpfJRO+CNJbKyzMhusWaXgz6DzjN0nFLxsY9op/bPga5Rh0Cam8ofrfMjYSg34jX+hWs80K907DpDNP5mPwMmovtja1F7GujzMfgRKdSfjOORJ1J8WD6OdZdZOOJ9Ao26yVcoLgx/oxGmHK6IMCCQJiIAkBAVAkBiPVAAHMNRwNT6Tb877xY3U+k2/O+8WdWPSMz7KgSAxEYILYIACAJDADNmh8lka7yUKovVSawGov5ZJJGbZL5LJXwW0PlsfrPMsyae3kpZwMu1Kshw4CUG52CaoND5bH6zzRkotVMm8dJe7U8pDGAlBudjT4NdHmo/Ay36ec7W10E16tQgo46C365dhBRnGTaQWmZp6ecI5l0CTZdq1ZBxwZC+G5r7iLogCQJiIILECAgME4AAPUAAHMNJwdR6Tb877xY3UekW/O+8UdaPSMz7BdKN8aYOK8VGFeUvidFbQRnztqqJRE30xVbcVuZqIcdiT6Dc/HrYjSQ8aTIwm1B2NrkdyFf+KMuqhGElwrBsjLMmuwRfHiuiiGOTUuRtcFKNMmuKY/k6lthF5eLB+xHOlNublklHdlbdidI1W6WLWYbMxOLUsdZ0qJcVabFSrX6nOBwyNWmDRFOlSWZjeTp6MItbLhrbRzlNqfFnrFFSyW7B0jTfpVhygK0tanNqSN0HxQWetCKo8OokJTe1phXIyWnrw8RRznDhs4WdSUkpJdpk1UMWqXaGKTumEkOdFfJ54VnBWqqrgzLGcjn5r/AEcyUnl77ZCCc75B8HR5GqS2ijHqqFU8x6GP0SlwPPQV10k0o9YQtToH0YgJINRA9OAAcs0nC1HpFvzvvFjdR6Rb877xR149IzPsF5S+J0V5v/Rz15S+J0P/AM/9GbUeCcRWnlmLXYXhHk4tmfTSxa12j9RLhqZVOL317GuiumlxOTC1/vRK6PyWRqnwzi0S2/yNB4NFm8Gc19Z0a5qyAiWlzPKewYpKFqQmrG6bapA3++kXWK4exGJ2/vcfURjFzbaG+DXqFmqRzjppqyG3QzOtJiec7EsU1FNMTVj6dq4i4POoYyUlXD4GfTS4rpMhFWnIZfVS4eFovZHlak0L1vkonST4ocL6h19ikg8jn5t/A5iWbMPoydSfkM5sY8VuO1k8PTFI3OcK6vFfQjnTk5ybZrt00Y1tpmTBPEl2hSIILYIwXET0oAByjScPUekW/O+8UN1HpFvzvvFnXj0jM+w9oz9RPGOoWAOKfYWCk4y4l0lrLZWLEigBtV2BeuyVa8Uiyx2eUVH11wdabe7eGJxSd0MTCcoPMWN/VTwPWnoy/G6u0pyVeOncg1CXaHyZ52yn0sqa1VTLO5KpockuL47kk0uEgoywslDoY39VPA3kKvF8bZvcW6q/1Kgn4j6yLUJdoORE7JTe7Jrm63mJqVFL4lxdHQVVFTTxLcdxqqCmZ7LZWLEiK7JVvMTU6aY8PjZytzLLHE8dAJJqqAu9TNrAtNqXEukCBqKXQhkr5yjh9ArBYgFFLoCMASAxHogADkmk4eo9It+d94sbqPSLfnfeLOvHpGd9kDoVwlBNvDFANoQ10w40lLb4l1RUt3P/ANMwCp+xmmVFTltPbHaUrri5tcWEvaJAKfsB6jW7UuJ8OCbKq0m4z/1kqtNY8e1ZB6aai28bC49jLxqrcIvjw307kKqv/Pf4i4UynByS2RKom3JL/iL9gMVdccZn/wCk8jXJ7T/9FWaedcOKXQyVprOFSXWH7AlwjC3DllYLuuqW6njbtFvTzay3v0ELTzab22eA49gWqhW5SU5bLoJdNTaXF/6KtqlVLhl0lB1fkRodFSi3x7/Eiqup1+NLxsiADa/YGn9PWlni2+JmksSaXQGXjGQBICAABiPQgAHINJxNR6Rb877xYzUekWfO+8odiPSM77IAkE8STYwIw+xg0+xml6iD3cFkl6mLwnBPBG36GZcPsBJ52Q6V0WmuFLJKvUa+FRWX1jt+hFVfbtjOwO+ySa33L16hQjhxyVd0eOMlBJJEa/wZWFs4R4VnBPL2JvGVku9RBvyEH6iHXBMP0BSdllkOGWcAtRYoqO+EX/UrGOHYlX1tSzBJ42D9AK5WxvO/STy1jykuvJMLlGOMdZf9TFPaCQfoBFk52SzLOSuH2M0/qa9m4IFqYdcFgLfoKMuH2EuLXUx1l0ZYxBLBd6qOEnBMLfoDL/oB11sbGuGPCKGhEASQMD0AABxzQYrPB/HZKXK44m3jh/JXm33v2/kALlnyLyR2oObfe/b+Q5t979v5AB/Pk9htQc2+9+38hzb737fyAB9Rk9htQc2e9+38hzb737fyAB8+T2G1BzZ737fyHNvvft/IAHz5PYbUHNnvft/Ic2e9+38gAfPk9htQc2e9+38hzZ737fyAC+fJ7Dag5s979v5I5s979v5AA+fJ7Dag5s999v5Dmz3v2/kAD58nsNqJ5s979v5Dmz3v2/kAD58nsNqI5s979v5J5s979v5AA+fJ7DYiObPe/b+Q5s979v5AA+fJ7DYjoAAFJI//2Q==[/img]