Guest Post by Fred Reed

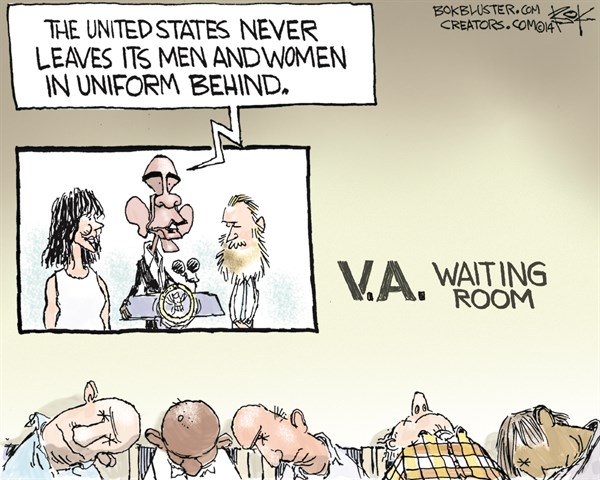

One Vet’s Take

June 6, 2014

It is so easy to gull the: the pack, the herd. It just takes a bit of theater. A brass band on the Fourth of July, flags whipping in the wind, young soldiers marching down Main Street, rhythmic thump-thump-thump of boots. There comes that glorious sense of common purpose, the adrenal thrill of collective power, thump-thump-thump. Martial ceremony is heady stuff, appealing to things deep and limbic. When Johnny comes marching home again, hoorah, hurrah. We are all together now, made whole, no petty divisions. The fanged herd.

Always the herd. It is in the genes. The herd. Basketball championship night, in a rural high-school: Bright lights, electrified crowd, cheerleaders twirling, skirts riding high. “Johnny, Johnny, he’s our man, if he can’t do it, nobody can!” Wild applause. Striplings dash onto the court, swirl into smooth fast lay-ups, cocky, confident. Long jump-shots, swish! Yaayyyy! Common purpose, unity.

For the seniors, next year in Afghanistan. Johnny comes rolling home again, hoorah, hoorah, minus his legs. From this we avert our eyes.

The herd. In a thousand Legion halls across the nation veterans gather on Memorial Day to make patriotic speeches. There are clichés about the ultimate sacrifice, defending our freedoms, God, duty, and country, our American way of life. Legionnaires are friendly, decent people, well-meaning—now, anyway. If there were an earthquake, they would pull the wounded from the rubble until they dropped from fatigue. They are not complex. They listen to the patriotic speeches with a sense of being a band of brothers. And if you told them they were suckers, conned by experts, used, they would erupt in fury, because somewhere inside many have suspected it.

The herd. The pack. Whip’em up. It’s for God, for democracy, onward Christian soldiers. We are a light to the world, a shining city on a hill, what all the earth would like to be if only they shared our values. We, knights in armor in a savage land, we fight fascism, Nazis, terror, Islam, it doesn’t matter what as we can always find something to fight, some sanctifying evil.

We are very like our enemies. We do not notice this. Carefully we do not notice. Guernica, the Warsaw ghetto, Fallujah, Nanjing—they are all the same. Soldiers are all the same, wars the same. All are fought on the most irreproachable moral grounds. We fight for peace, for freedom, for Allah, for the Fatherland, the Motherland, for the Homeland, for white Christian motherhood. We do not fight for Lockheed-Martin, or for oil. Oh no. Even the suckers might revolt at dying for low-sulfur crude, or Caspian pipelines.

People are squeamish these days, so we hide the horror of what we do. The public might gag and say, “No. No more.” Besides, we do not want to discourage recruiting. In our Fallujahs we do not show the rotting corpses, or footage of the disemboweled as they try to crawl, god knows to where, while they bleed to death.

And we do not show Johnny with his new colostomy bag, or blind, or with three stumps and one partial arm, or paraplegic or, never, ever, the quads, paralyzed below the neck, lying on slabs, turned over from time to time to avoid bed sores. The public does not see—though I have seen—the seventeen-year-old sweetheart of the young Marine from Memphis, when she first sees her betrothed irremediably blind with half his face a hideous mass of mangled flesh—and her obvious thought, oh Jesus, Johnny, oh Johnny, how can I do this? Onward Christian soldiers.

In my day we girded our loins against the Soviet Union, the Evil Empire, that spied on its citizens, tortured people it didn’t like, and committed atrocities in Afghanistan, where it had no business being. We loved the Afghans. We wanted to save them from the godless communist invaders.

To protect people from communism, we killed millions of them, only incidentally making McDonnell-Douglass rich. Today we spread a swath of destruction across the planet, this time protecting people from Terror by murdering them with drones.

But let us not think of these things. At all costs we must maintain patriotic unanimity, the idea that Our Boys are selflessly Serving America. Actually they do it because they have no choice. Offer them a chance to come home without penalty and see what happens.

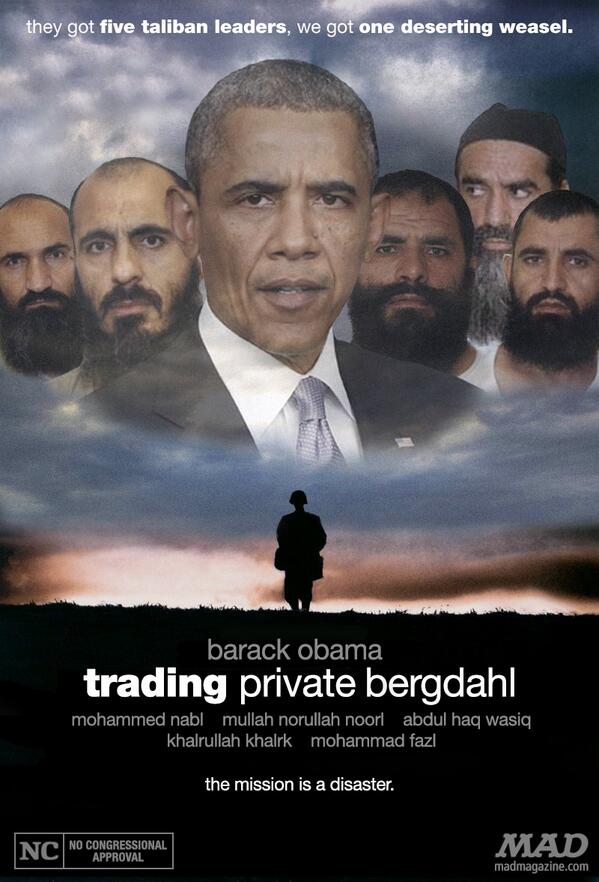

To make them fight we have heavy punishments for desertion, for treason, and for mutiny. Escape comes quickly to the minds of men compelled to die in wars that mean nothing to them in remote countries that mean less. Escape must be prevented. Thus the cries of “Traitor!” and “Commie!” and “Coward!” The pack instinct runs strong, but self-preservation runs stronger. It must be suppressed ruthlessly.

Flags whipping in the wind, thump-thump-thump, brass band, Stars and Stripes Forever, maybe a few F-16s howling overhead to set hearts a’pounding, unity. Politicians will speak of gratitude to Our Boys.

Except of course that there is no unity, and few are grateful. Most of the country isn’t interested in the wars. A majority don’t know where Afghanistan is. The wealthy, the Ivy students en route to careers in I-banking, and for that matter most college kids have never seen a military base and don’t want to. The small-town, lower-middle class South and West—the suckers grow thickly there. Yale has never heard of Farmville. And doesn’t want to, and won’t.

There is another reason why veterans rage at any deviation from the tales of nobility and sacrifice. Two choices exist for a man who has been mutilated in the hobbyist wars of Washington’s neocon pansies. He can believe desperately that he became a lifelong cripple in a worthy cause. God. Duty. Country. He can believe that he is appreciated. He can hope, or pray, that it was somehow worth it.

Or he can realize that he has been suckered, snookered, conned. This can be hard to bear, very hard. It will get worse when a few years have rolled by and the new generation begins to ask, “Wasn’t there some kind of war in Afghanistan or somewhere? Maybe it was Africa.”

Men engaged in killing for petroleum can develop a suspicion that what they do is just wrong. Soldiers are trained, conditioned by experts, to do things that the civilized finds abhorrent. If a veteran begins to doubt the justness of the war, then he becomes no more than a hired murderer. This is not pleasant. Thus no one must be permitted to say it. A contagion might result.

God forbid that soldiers begin to think. Independence of mind is dangerous to militaries. Training is chiefly a means of preventing it. Infrequently a soldier has the courage to see that what he is doing is both stupid and immoral, and walk away from it. Bowe Bergdahl did. I say, speaking as a former Marine in Viet Nam, and as a life member of both the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the Disabled Veterans of America: You have my admiration, Sergeant Bergdahl.