John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

Ockham’s razor is a principle that states that among various hypotheses that might be used to explain a set of observations, the hypothesis – consistent with the evidence – that relies on the smallest number of assumptions is generally preferred. Essentially, the razor shaves away what is unnecessary and retains the most compact explanation that is consistent with the data. The same basic principle runs through the history of thought from Ptolemy (“We consider it a good principle to explain the phenomena by the simplest hypothesis possible”) to Einstein (“A theory should be made as simple as possible, but not so simple that it does not conform to reality”).

Suppose, for example, that one periodically sets hot cherry pies near the window to cool, and sometimes they disappear, with an empty pie tin usually later found in the kids’ treehouse, and cherry stains around their lips. When pies go missing, one would normally not assume that aliens had come down to earth, taken the pie, devoured it in mid-air, brushed by the kids’ lips leaving cherry stains in the process, erased the kids’ memory, discarded the tin in the treehouse, and then returned to Xenon.

When we observe the increasingly tortured arguments that “this time is different,” we see investors discarding straightforward explanations that are fully consistent with the evidence and opting instead for the aliens-from-Xenon theory.

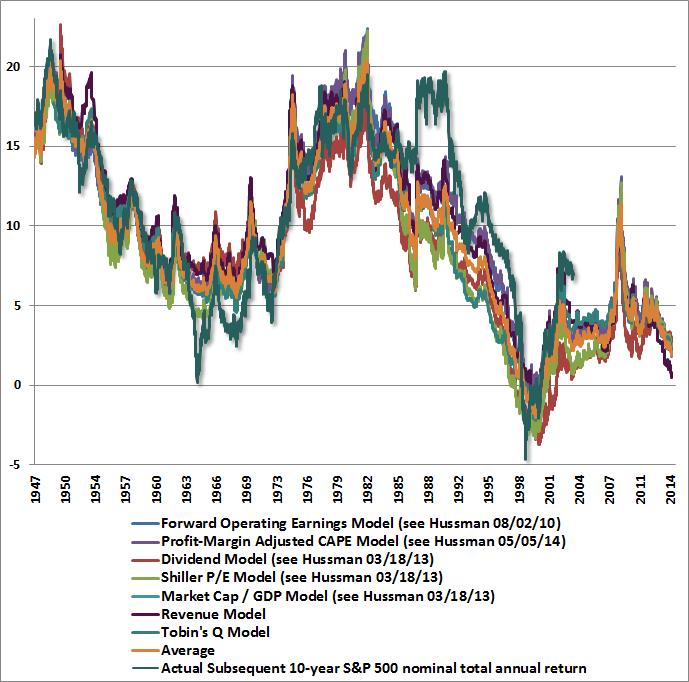

Ockham’s razor is very straightforward here. As much as investors seem to want to believe that aliens from Xenon have brought some brave new world, our valuation approach is consistent with a century of market history and has not missed a beat even in recent market cycles. We continue to view long-term prospects for the stock market as dismal at present valuations.

We increasingly see investors believing that history is no longer informative, and that the Federal Reserve has finally discovered how to produce perpetually rising markets and can intervene without consequence to support the markets and the economy indefinitely. Maybe it’s no longer true that valuations are related to subsequent returns. Maybe, contrary to all historical experience, reliable measures of valuation that have had a 90% correlation with actual subsequent market returns can now remain at double their historical norms forever, thereby allowing capital gains to be unhindered by any future retreat in valuation multiples as fundamentals grow over time. It’s just that one must also rely on valuations never retreating, because even if earnings grow at 6% annually indefinitely, and the CAPE simply touches a historically-normal level of 16 even 20 years from today, the total return on stocks, including dividends, would still be expected to average only 5% annually over that horizon. That’s just arithmetic.

Investors should also note the following. At present, the most historically reliable valuation measures average more than 110% above their pre-bubble historical norms. Secular bear market lows don’t occur very often, but when they do, valuations typically average about 50% of pre-bubble norms. Here’s some arithmetic. Assuming constant 6% annual growth in nominal fundamentals, if the stock market was to experience a secular bear market low 25 years from now, the S&P 500 Index would be unchanged from present levels. Checking those numbers is good practice [1.06 * (0.5/2.1)^(1/25) = 1.00]. Market valuations leave no margin for error, even over the long-term.

Meanwhile, nothing even in recent market cycles provides any support to the assumption of permanently elevated valuations. The only support for it is the desire of investors to avoid contemplating outcomes the same as the market suffered the last two times around. “This time is different” requires a lot of counterfactual assumptions. Ockham’s razor would suggest a nice shave.

For that reason, we are much more comfortable estimating long-term total returns directly, rather than converting them to a price that we think is “fair.” The “fair” price always embeds some assumption about future returns, and investors may very well differ on what is fair. Frankly, if you think that an asset class that is quite capable of repeatedly losing half of its value should compensate for that risk with historically normal total returns of about 10% annually over time, I would tell you that “fair value” is about 950 on the S&P 500.

“Occam’s razor” in fact…

While I would prefer peach pie, aliens (yellen) are in charge of the stock market and I am not playing with them.

Hi there! I understand this is sort of off-topic

but I needed to ask. Does running a well-established website such as yours require a lot of work?

I’m completely new to blogging but I do write in my journal every day.

I’d like to start a blog so I can share my experience and views online.

Please let me know if you have any ideas or tips for

brand new aspiring blog owners. Thankyou!

Take a look at my web site; Service Demenagement Martin