How do you design a utopia? In 1972, John B. Calhoun detailed the specifications of his Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice: a practical utopia built in the laboratory. Every aspect of Universe 25—as this particular model was called—was pitched to cater for the well-being of its rodent residents and increase their lifespan. The Universe took the form of a tank, 101 inches square, enclosed by walls 54 inches high. The first 37 inches of wall was structured so the mice could climb up, but they were prevented from escaping by 17 inches of bare wall above. Each wall had sixteen vertical mesh tunnels—call them stairwells—soldered to it. Four horizontal corridors opened off each stairwell, each leading to four nesting boxes. That means 256 boxes in total, each capable of housing fifteen mice. There was abundant clean food, water, and nesting material. The Universe was cleaned every four to eight weeks. There were no predators, the temperature was kept at a steady 68°F, and the mice were a disease-free elite selected from the National Institutes of Health’s breeding colony. Heaven.

Four breeding pairs of mice were moved in on day one. After 104 days of upheaval as they familiarized themselves with their new world, they started to reproduce. In their fully catered paradise, the population increased exponentially, doubling every fifty-five days. Those were the good times, as the mice feasted on the fruited plain. To its members, the mouse civilization of Universe 25 must have seemed prosperous indeed. But its downfall was already certain—not just stagnation, but total and inevitable destruction.

Calhoun’s concern was the problem of abundance: overpopulation. As the name Universe 25 suggests, it was not the first time Calhoun had built a world for rodents. He had been building utopian environments for rats and mice since the 1940s, with thoroughly consistent results. Heaven always turned into hell. They were a warning, made in a postwar society already rife with alarm over the soaring population of the United States and the world. Pioneering ecologists such as William Vogt and Fairfield Osborn were cautioning that the growing population was putting pressure on food and other natural resources as early as 1948, and both published bestsellers on the subject. The issue made the cover of Time magazine in January 1960. In 1968, Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, an alarmist work suggesting that the overcrowded world was about to be swept by famine and resource wars. After Ehrlich appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in 1970, his book became a phenomenal success. By 1972, the issue reached its mainstream peak with the report of the Rockefeller Commission on US Population, which recommended that population growth be slowed or even reversed.

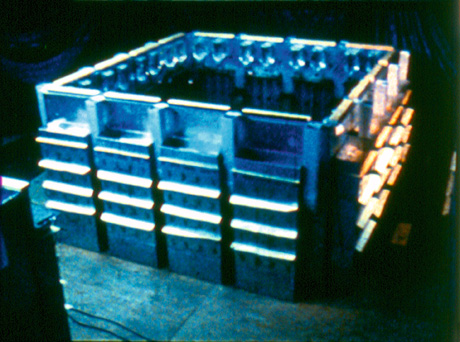

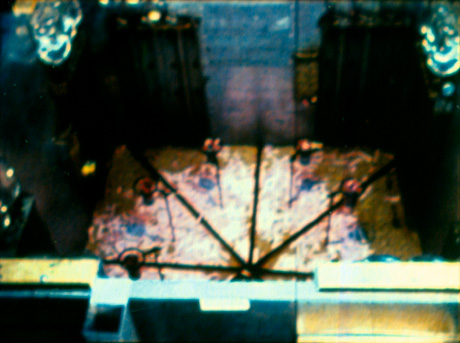

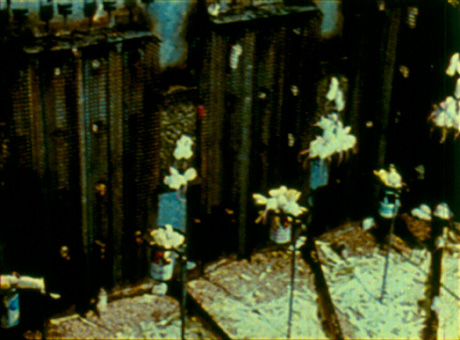

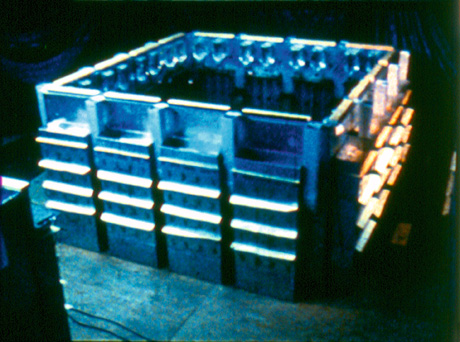

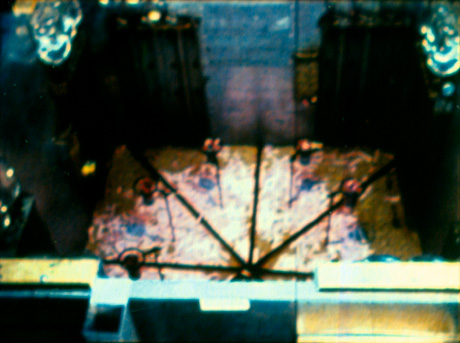

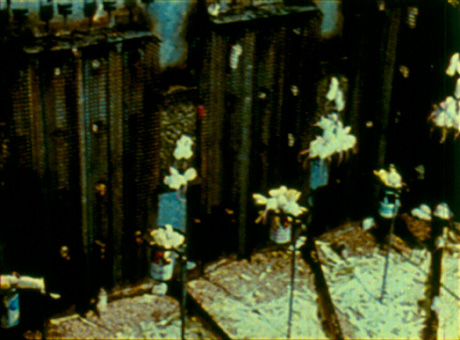

Mouse utopia/dystopia, as designed by John B. Calhoun (middle and bottom). All images from Animal Populations: Nature’s Checks and Balances, 1983.

But Calhoun’s work was different. Vogt, Ehrlich, and the others were neo-Malthusians, arguing that population growth would cause our demise by exhausting our natural resources, leading to starvation and conflict. But there was no scarcity of food and water in Calhoun’s universe. The only thing that was in short supply was space. This was, after all, “heaven”—a title Calhoun deliberately used with pitch-black irony. The point was that crowding itself could destroy a society before famine even got a chance. In Calhoun’s heaven, hell was other mice.

So what exactly happened in Universe 25? Past day 315, population growth slowed. More than six hundred mice now lived in Universe 25, constantly rubbing shoulders on their way up and down the stairwells to eat, drink, and sleep. Mice found themselves born into a world that was more crowded every day, and there were far more mice than meaningful social roles. With more and more peers to defend against, males found it difficult and stressful to defend their territory, so they abandoned the activity. Normal social discourse within the mouse community broke down, and with it the ability of mice to form social bonds. The failures and dropouts congregated in large groups in the middle of the enclosure, their listless withdrawal occasionally interrupted by spasms and waves of pointless violence. The victims of these random attacks became attackers. Left on their own in nests subject to invasion, nursing females attacked their own young. Procreation slumped, infant abandonment and mortality soared. Lone females retreated to isolated nesting boxes on penthouse levels. Other males, a group Calhoun termed “the beautiful ones,” never sought sex and never fought—they just ate, slept, and groomed, wrapped in narcissistic introspection. Elsewhere, cannibalism, pansexualism, and violence became endemic. Mouse society had collapsed.

Mouse utopia/dystopia, as designed by John B. Calhoun. All images from Animal Populations: Nature’s Checks and Balances, 1983.

On day 560, a little more than eighteen months into the experiment, the population peaked at 2,200 mice and its growth ceased. A few mice survived past weaning until day six hundred, after which there were few pregnancies and no surviving young. As the population had ceased to regenerate itself, its path to extinction was clear. There would be no recovery, not even after numbers had dwindled back to those of the heady early days of the Universe. The mice had lost the capacity to rebuild their numbers—many of the mice that could still conceive, such as the “beautiful ones” and their secluded singleton female counterparts, had lost the social ability to do so. In a way, the creatures had ceased to be mice long before their death—a “first death,” as Calhoun put it, ruining their spirit and their society as thoroughly as the later “second death” of the physical body.

Calhoun had built his career on this basic experiment and its consistent results ever since erecting his first “rat city” on a quarter-acre of land adjacent to his home in Towson, Maryland, in 1947. The population of that first pen had peaked at 200 and stabilized at 150, when Calhoun had estimated that it could rise to as many as 5,000—something was evidently amiss. In 1954, Calhoun was employed by the National Institute of Mental Health in Rockville, Maryland, where he would remain for three decades. He built a ten-by-fourteen-foot “universe” for a small population of rats, divided by electrified barriers into four rooms connected by narrow ramps. Food and water were plentiful, but space was tight, capable of supporting a maximum of forty-eight rats. The population reached eighty before succumbing to the same catastrophes that would afflict Universe 25: explosive violence, hypersexual activity followed by asexuality, and self-destruction.

In 1962, Calhoun published a paper called “Population Density and Social Pathology” in Scientific American, laying out his conclusion: overpopulation meant social collapse followed by extinction. The more he repeated the experiment, the more the outcome came to seem inevitable, fixed with the rigor of a scientific equation. By the time he wrote about the decline and fall of Universe 25 in 1972, he even laid out its fate in equation form:

Mortality, bodily death = the second death Drastic reduction of mortality = death of the second death = death squared = (death)2 (Death)2 leads to dissolution of social organization = death of the establishment Death of the establishment leads to spiritual death = loss of capacity to engage in behaviors essential to species survival = the first death Therefore: (Death)2 = the first death

This formula might apply to rats and mice—but could the same happen to humankind? For Calhoun, there was little question about it. No matter how sophisticated we considered ourselves to be, once the number of individuals capable of filling roles greatly exceeded the number of roles,

only violence and disruption of social organization can follow. … Individuals born under these circumstances will be so out of touch with reality as to be incapable even of alienation. Their most complex behaviors will become fragmented. Acquisition, creation and utilization of ideas appropriate for life in a post-industrial cultural-conceptual-technological society will have been blocked.

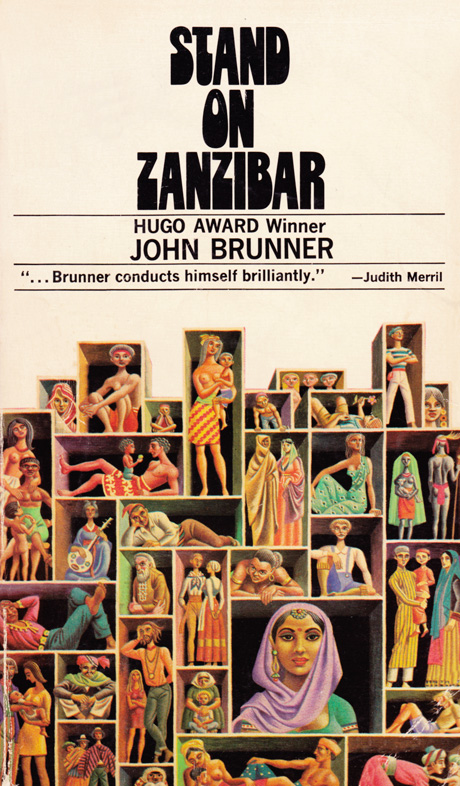

Cover of John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar, 1968. Brunner’s title comes from the notion that the world’s population in 1968 could fit (if everyone were standing tightly together) on the Isle of Man, while the projected population in 2010 would fit on the larger island of Zanzibar. Courtesy Grant Thiessen/BookIT.

If its growth continued unchecked, human society would succumb to nihilism and collapse, meaning the death of the species. Calhoun’s death-squared formula was for social pessimists what the laws of thermodynamics are for physicists. It was a sandwich board with “The End Is Nigh” written on one side, and “QED” on the other. Indeed, the plight of Calhoun’s rats and mice is one we easily identify with—we put ourselves in the place of the mice, mentally inhabit the mouse universe, and cannot help but see ways in which it is like our own crowding world.

This is precisely what Calhoun intended, in the design of his experiments and the language he used to describe them. Universe 25 resembles the utopian, modernist urban fantasies of architects such as Ludwig Hilberseimer. Calhoun referred to the dwelling places within his Universes as “tower blocks” and “walk-up apartments.” As well as the preening “beautiful ones,” he refers to “juvenile delinquents” and “dropouts.” This handy use of anthropomorphism is unusual in a scientist—we are being invited to draw parallels with human society.

And that lesson found a ready audience. “Population Density and Social Pathology” was, for an academic paper, a smash hit, being cited up to 150 times a year. Particularly effective was Calhoun’s name for the point past which the slide into breakdown becomes irretrievable: the “behavioral sink.” “The unhealthy connotations of the term are not accidental,” Calhoun noted drily. The “sink,” a para-pathology of shared hopelessness, drew in pathological behavior and exacerbated its effects. Once the event horizon of the behavioral sink was passed, the end was certain. Pathological behavior would escalate beyond any possibility of control. The writer Tom Wolfe alighted on the phrase and deployed it in his lament for the declining New York City, “O Rotten Gotham! Sliding Down into the Behavioral Sink,” anthologized in The Pump House Gang in 1968. “It got to be easy to look at New Yorkers as animals,” Wolfe wrote, “especially looking down from some place like a balcony at Grand Central at the rush hour Friday afternoon. The floor was filled with the poor white humans, running around, dodging, blinking their eyes, making a sound like a pen full of starlings or rats or something.” The behavioral sink meshed neatly with Wolfe’s pessimism about the modern city, and his grim view of modernist housing projects as breeding grounds for degeneration and atavism.

Wolfe wasn’t alone. The warnings inherent in Calhoun’s research fell on fertile ground in the 1960s, with social policy grappling helplessly with the problems of the inner cities: violence, rape, drugs, family breakdown. A rich literature of overpopulation emerged from the stew, and when we look at Calhoun’s rodent universes today, we can see in them aspects of that literature. In the 1973 film Soylent Green, based on Harry Harrison’s 1966 novel Make Room! Make Room!, the population of a grotesquely crowded New York is mired in passivity and dependent on food handouts which, it emerges, are derived from human corpses. In Stand on Zanzibar, John Brunner’s 1972 novel of a hyperactive, overpopulated world, society is plagued by “muckers,” individuals who suddenly and for no obvious reason run amok, killing and wounding others. When we hear of the death throes of Universe 25—the cannibalism, withdrawal, and random violence—these are the works that come to mind. The ultraviolence-dispensing, gang-raping, purposeless “droogs” of Antony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange, which appeared in the same year as Calhoun’s Scientific American paper, are the very image of some of the uglier products of mouse utopia.

Poster for Soylent Green, 1973. The film depicts a futuristic society in which overpopulation is so catastrophic and food in such short supply that the populace survives on rations of the titular food product, which turns out to be made from processed human flesh.

Calhoun’s research remains a touchstone for a particular kind of pessimistic worldview. And, in the way that writers like Wolfe and the historian Lewis Mumford deployed reference to it, it can be seen as bleakly reactionary, a warning against cosmopolitanism or welfare dependence, which might sap the spirit and put us on the skids to the behavioral sink. As such, it found fans among conservative Christians; Calhoun even met the pope in 1974. But in fact the full span of Calhoun’s research had a more positive slant. The misery of the rodent universes was not uniform—it had contours, and some did better than others. Calhoun consistently found that those animals better able to handle high numbers of social interactions fared comparatively well. “High social velocity” mice were the winners in hell. As for the losers, Calhoun found they sometimes became more creative, exhibiting an un-mouse-like drive to innovate. They were forced to, in order to survive.

Later in his career, Calhoun worked to build universes that maximized this kind of creativity and minimized the ill effects of overcrowding. He disagreed with Ehrlich and Vogt that restrictions on reproduction were the only possible response to overpopulation. Man, he argued, was a positive animal, and creativity and design could solve our problems. He advocated overcoming the limitations of the planet, and as part of a multidisciplinary group called the Space Cadets promoted the colonization of space. It was a source of lasting dismay to Calhoun that his research primarily served as encouragement to pessimists and reactionaries, rather than stimulating the kind of hopeful approach to mankind’s problems that he preferred. More cheerfully, however, the one work of fiction that stems directly from Calhoun’s work, rather than the stew of gloom that it was stirred into, is optimistic, and expands imaginatively on his attempts to spur creative thought in rodents. This is Robert C. O’Brien’s book for children, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, about a colony of super-intelligent and self-reliant rats that have escaped from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Sources: Edmund Ramsden & Jon Adams, “Escaping the Laboratory: The Rodent Experiments of John B. Calhoun & Their Cultural Influence,” The Journal of Social History, vol. 42, no. 3 (2009). Available as a working paper at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/22514/.

John B. Calhoun, “Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population,” in Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 66 (January 1973), pp. 80–88. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1644264.

John B. Calhoun, “Population Density and Social Pathology,” Scientific American, vol. 206, no. 2 (February 1962), pp. 139–150. Available at http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1963-02809-001.

Will Wiles is a London-based author and journalist. He is deputy editor of Icon, a monthly architecture and design magazine. His debut novel, Care of Wooden Floors, will be published by HarperPress in February 2012.